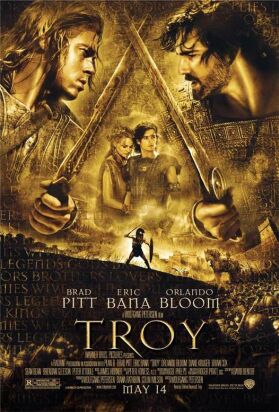

Troy

The Trojan War is almost the definition of an epic subject. Not only are the three greatest epics in the Western tradition — The Iliad, The Odyssey and The Aeneid — inspired by it but so are a host of lesser works in the Western vernaculars, many of them taking a leaf out of Virgil’s book by claiming Trojan origins for heroes or nations as a way of affirming their greatness. Epic implies spaciousness, both of form and content. In form it is the opposite of the concentrated, lyric style. Originating in an oral tradition, it repeats itself, it expands metaphors instead of making them concise, and it often includes long lists of names for the sheer pleasure of repeating them. Usually it takes place over a long period of time and includes roles for Olympian figures above the earth and infernal ones below it.

Wolfgang Peterson’s movie Troy takes an epic subject — the epic subject — but apart from its near three-hours’ length he does not give it an epic treatment. Instead of the decade that the war is said to have taken in ancient epic, here it seems to take place in only a few days. The gods make no appearance apart from a brief cameo by Thetis (Julie Christie), the mother of Achilles (Brad Pitt), while both the ferryman and the shades of the dead that he rows to the other side of the River Styx are mentioned, but never seen. Most importantly, Peterson conveys no sense of epic detachment. The sublimity of Homer depends on his own serene and god-like distance from the characters and their actions, to the point that he can seem almost heartless. Peterson is by contrast passionately involved with the people and the events that he portrays. He has turned the tale of Troy into a romance, and a romance much closer to the sword-and-sandal movie epics of the 1950s than it is to Homeric epic.

This has both its bad and good sides. I never thought to see in the 21st century a cinematic sight to compare with Peter O’Toole’s King Priam as he puts a fatherly hand on the shoulder of Paris (Orlando Bloom), just arrived from Sparta with Helen of Troy (Diane Kruger), and asks: “Do you love her?” Oh dear, oh dear! It’s not as if we ever supposed we were watching through a window into Bronze Age Asia Minor, but the carefully cultivated illusion of a Never-Never Land somewhere between that time and our own is shattered at this point. Such lapses aside, however, I am more impressed that Peterson and his screenwriter, David Benioff have given us the 1950s without irony than I would be if they had given us the second millenium BCE with irony. In doing so they have trimmed down the story not only in terms of time but in terms of action. In Homer or Virgil, what happens before and after the events of their narratives is as important as the narratives themselves. In Troy everything, or almost everything, is self-contained.

Thus, instead of recovering Helen from the ruins of Troy and dragging her back to Sparta, Menelaus (Brendan Gleeson) is killed by Hector (Eric Bana) after humiliating Paris in single combat before the walls of Troy. Instead of returning home in triumph only to be murdered in his bath by his wife, Agamemnon (Brian Cox) is stabbed in the neck by Briseis (Rose Byrne), the Trojan princess-prisoner whom he had taken from Achilles before being forced to give her back. Although this leads to a different ending from anything imaginable by Homer — one which, not to give too much away, is very good news for Hector’s baby son, Astyanax — I was often pleasantly surprised by how effectively Peterson presents what is left of Homer as cinema. Though I have never been a fan of Brad Pitt’s, his portrayal of the icy menace and feline grace of Achilles worked very well I thought. And it wasn’t his fault that he had to speak (to Briseis) the line: “You gave me peace in a lifetime of war.”

Likewise, Mr Bana’s Hector, Mr Bloom’s Paris and Mr O’Toole’s Priam are marvellously human. Together with Briseis and Hector’s wife, Andromache (Saffron Burrows), they manage to create in us a sense of the cultivation, the gentleness and piety of the Trojans, which makes sense of Helen’s decision to flee from Sparta with Paris. For the Greeks are by contrast uniformly brutal and thuggish. Among them only Sean Bean’s Odysseus, besides Achilles, seems the least bit interesting or sympathetic. Yet they are also a sign that Peterson’s sense of the Realpolitik behind the Trojan war has survived the sentimentality that is always threatening to creep in around the edges. At times this has a very contemporary ring, as when Odysseus pleads with the other Greeks to hang tough when things are going badly: “If we leave now, we lose all credibility; if the Trojans can beat us so easily, how long before the Hittites invade?”

Of course that is put much more as our contemporaries would put it than as Homer’s would, and I wondered if there wasn’t even a more specific allusion to current affairs when doddery old King Priam goes with the advice of the priest — that is to say the religious nut — who assures him of victory rather than the rational advice unsanctioned by the supernatural which Hector gives him. But much may be forgiven for the sake of the fact that, as you might expect from the director of Das Boot, one of the greatest of war movies, Peterson is able to give us an understanding of the hunger for honor and glory of men in war. Sometimes he does so rather heavy-handedly, as in the voiceovers by Odysseus that begin and end the movie, but he is also capable of enough delicacy to convey the subtle difference between the Greek and the Trojan conceptions of honor.

This is nicely summed up in two parallel scenes between two pairs of brothers. In one we see Agamemnon saying to Menelaus that “Peace is for the women and the weak. . .The gods protect the strong.” In the other we see Hector reproving Paris for his willingness to go to war for Helen: “There is nothing glorious about war,” he says. Of course there is a lot that is glorious about war, as this film was designed to show. But honor may also be tempered by human feeling, as it is among the Trojans and, just for an instant, in Achilles when Priam comes to him to beg for his son’s body. At such moments we may think that Peterson’s movie, though no epic, really is a tract for our times.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.