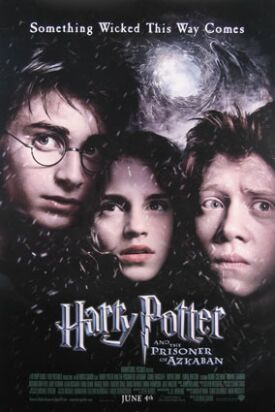

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

Now, children of Hogwarts, for this week’s lesson in movie wizardry. First into the cauldron go your visuals, and for that Mr Alfonso Cuarón, director of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban has provided us with some splendid ingredients. His depiction of Hogwarts itself is his finest achievement. He manages to make its castle-like structure look remarkably persuasive as an ancient English school or college at which for centuries pupils have applied themselves to the learning of ancient wisdom in beautiful, cloistered surroundings. Only here the Gothic architecture of the school’s medieval hall is as jazzed up and alive with new significance as the ancient wisdom itself. Perhaps even those generations of Mr Chipses, the teachers of now-disregarded lessons in Latin and Greek, would be flattered to think of themselves as turning out boy wizards — as in their plodding, non-cinematic way they were.

Mr Cuarón is particularly good at evoking the sense of a nameless dread. While Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe) and his friends Hermione Granger (Emma Watson) and Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint) are on the train to Hogwarts, it suddenly stops without apparent reason, and the camera pulls back to show the train on a lonely viaduct over a deep gorge as dusk falls and the lights go out and ice begins to form on the windows. But that kind of scariness is, like every other kind in this movie, quickly dissipated. When a monster — a giant, hooded, wraith-like creature known as a “Dementor” — appears, floating through the carriages, it is so much less scary than the anticipation of it that it seems anti-climactic. Then Harry faints and comes to when everything is back to a comfortable normal.

And that, children, is the reason why Mr Cuarón’s potion works such inferior magic. He has neglected to add the drama. Or rather, having been imposed upon by some dwarf or troll purporting to sell magic ingredients, he has added a bogus drama without any of the bite of the real thing. Actually, I suspect that the vendor of artificial drama was Miss J.K. Rowling, author of the mega-best-selling Harry Potter books on which the film is based. But, not having read any of them, I can’t be sure.

So, children, you may be asking yourselves: “How do I tell the weak, impotent, factitious drama that spoils the potion from the full-strength, genuine article?” I will tell you. That is why you are at Hogwarts. In a real drama, events appear to follow on from one another — indeed, each makes the next seem almost inevitable. This is because, in our own lives, we see that events have consequences. If you do a, then b will follow. We like and even need that thread of connection, a to b to c and so forth, because it makes the drama seem real, no matter how much magic there is in it.

But the cheap imitation drama doesn’t give us this. Events follow each other in a random sequence and nothing leads to anything else. In one scene our hero is making his overbearing auntie blow up like a balloon and in the next he is riding a phantom bus, listening to a shrunken and disembodied head talk to him in a Jamaican patois. Neither the auntie, nor the bus, with its driver and conductor, nor the Jamaican head ever appears again. They are all whisked on and off the screen as part of a dream-like phantasmagoria, but they lead to nothing else. Even when, for a spell, one thing does seem to lead to another, we quickly find that it is not so. A bad guy suddenly becomes a good guy without explanation, and another bad guy out of nowhere is put in his place. Dire events happen — well, semi-dire events — and somebody goes back in time to change things so that they do not happen.

The wicked witch who is trying to sell this fake drama as if it were real might try to persuade you that children today don’t really care about drama anyway. All their poor little stunted attention-spans can cope with is one exciting visual image’s following another. They don’t want or need any thread of connection between them. Do not listen to her, children. For proper magic always has one foot in reality. It has to make you believe, if only for an instant, that it could really happen. Nobody but a fool will ever believe that about Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. And what do you go to school for unless it is to learn how not to be a fool?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.