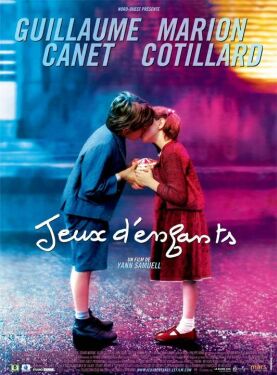

Jeux d’Enfants (Love Me If You Dare)

America’s francophobia of the past couple of years, with its “freedom fries” and “freedom toast” — did anybody ever try freedom kissing I wonder? — has always been more of a joke than French anti-Americanism, which takes its darker, more serious character from the natural cynicism and paranoia of the French. But the mutual incomprehension of our two countries is nicely illustrated by Yann Samuell’s film Love Me If You Dare, which he directed and co-wrote with Jacky Cukier. Start with the title. In French it is Jeux d’enfants or “Children’s Games.” The American distributors must have seen at once that the irony, the multiple levels of suggestiveness of such a title would only have confused us simple-minded Yanks. So they named it for the particular game of dare played by a French boy and girl, Julien and Sophie, who meet as children (Thibault Verhaeghe and Joséphine Lebas-Joly) and preserve their weirdly private and exclusive relationship as adults (Guillaume Canet and Marion Cotillard).

Among the losses in this translation is the link to the French film it most resembles, Jean-Pierre Melville’s adaptation of Jean Cocteau’s Les Enfants Terribles (1950) — which, if it were re-made today would doubtless come to America as: “Those Darned Kids!” I thought this was just a joke until I saw on the invaluable IMDB (or Internet Movie Data-base) under Enfants Terrible the recommendation: “If you like this title, we also recommend Freaky Friday.” Like Melville, Samuell creates a bond between his two children out of one’s vulnerability and the other’s volunteering as protector, but although the contemporary director wants to be in some ways as “transgressive” — to use a term that the French have also given us — as his great predecessor, he misses a few tricks.

For instance: the children are not brother and sister, as in Cocteau/Melville, so the extra spice given to the mix by the undertones of incest is missing. And it is the boy who becomes the protector of the girl, when she is teased because of her Polish ancestry, rather than the other way round, suggesting an almost chivalric subtext. Surely some mistake there? Finally, the more traditional male-female set-up chimes with Love Me’s omission of the homoerotic element in Cocteau.

What was Samuell thinking?

Let me see if I can guess. Like Les Enfants Terrible, Jeux d’Enfants aims to create for us an image of a childish world preserved beyond its natural span, a world from which adults and adult values are rigidly excluded and the childish game of dare, cap ou pas cap, survives puberty to destroy every prospect of “normal” social and sexual relations for those who cannot stop playing it — though the sex between the two principals remains mostly subliminal. Sophie’s Polish-speaking parents are never anything but an embarrassment to her, and they do not appear, even to Julien, who loses his own mother (Emmanuelle Grönvold) to cancer and retreats into his private relationship with Sophie when his taciturn, melancholy father (Gérard Watkins) tries to discipline him. Eventually, his father disowns him completely.

A key moment in the film comes when Julien and Sophie, both aged eight, are being lectured after their latest bit of misbehavior by the headmaster of their school on the need for discipline. Without discipline, he says, there can be no respect, and without respect civilization itself must fall. Julien, on yet another dare, responds by unbuttoning his shorts and urinating on the carpet. That’s the post-1918 French for you, forever oui-oui-ing on the pathetic remains of the civilization they once did so much to create as proof of their existential bona fides. Yet that characterization is much more accurate as applied to Cocteau than to Yann Samuell. Sure the latter goes through all the motions, comparing the destructive relationship of Julien and Sophie to drug addiction — nearly always a romantic thing in French movies — and contrasting the glorious rush of dare and counter-dare with that favorite French punching bag, bourgeois suburban life. Above all, he is willing, even eager, to treat as expendable all those meaner-spirited bourgeois who are unfortunate enough to have any part in the lives of the happily unhappy couple. In particular, not only Julien’s father, but a fiancée, a wife and two children are all contemptuously kicked to the curb for their foolishness in trying to love him.

There’s the authentic French touch all right, but Samuell is a little lacking in the courage of his convictions, I think. Cocteau/Melville saw that their terrible enfants were on the express train to a violent end and positively gloried in the fact. Samuell draws back from such a stark and uncompromising conclusion, instead giving us a choice of endings: one a French intellectual’s symbolic martyrdom, encased in concrete at the foundation of yet another of civilization’s monuments, and the other rife with the imagery of love and even a paean to marriage. Is the first a fantasy and the second a reality? Or is the second the dying dream of the first?

There is no way to tell anything about it except that Samuell is seeking some kind of accommodation with the bourgeois enemy, a way of reconciling the heady nihilism of French culture dating back to Céline — which must have become as much of a burden to Samuell’s generation as the pre-First World War honor culture was to the Dadaists and Surrealists and their successors — and something that looks suspiciously like, well, civilization. Lest we get any ideas of that sort, perhaps, he has his aged Julien (Robert Willar) pee on the carpet again, to the unspeakable admiration of the aged Sophie (Nathalie Nattier). But I’m not buying it. Secretly, the French themselves are getting a little tired of their cultural enfants terribles and long to rejoin the civilized world. We should welcome them back.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.