The Summer of their Discontent

From The American SpectatorOh for the days when the “summer blockbuster” season only meant one after another of special-effects-laden slabs of generic “entertainment” — usually about comic-book heroes — intended for the amusement of the most pampered and ignorant 12 year-olds who have ever walked the earth. That our best and brightest artistic talents have been employed in such an enterprise has always been a shame and a scandal, but I have thought hitherto that its most pernicious results would be long-term — the cultural equivalent of smoking. If so, the cancer diagnosis has just come back, and the prognosis is not good. Hollywood’s production of self-indulgence, paranoia-chic, a toxic combination of political naïveté and tendentiousness and what was called, in connection with the 9/11 Commission’s report in July, “Groupthink” has metastasized and is now growing out of control.

The most egregious offender was, of course, Michael Moore, whose Fahrenheit 9/11 outdid even his own previous efforts in unscrupulous, unnuanced and unmitigated propaganda laced with buffoonery. But Moore seemed positively restrained in comparison with Robert Kane Pappas’s Orwell Rolls in His Grave. Both films lodge the most vile slanders against the president and vice-president of the United States on the basis of nothing but innuendo and conjecture, but the latter grows so carried away with its own lunatic inventions that it extends them back in time to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, which it attempts to taint by resurrecting the long-discredited “October surprise” allegations of Gary Sick.

Both films are classed as documentaries, though in neither is there so much as a single dissenting voice. The same is true of Joel Bakan’s The Corporation (directed by Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbot) — which manages to make even Milton Friedman sound like an “anti-globalization” nut — and Howard Zinn: You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train. Zinn, the author of the People’s History of the United States also appears as one of the left-wing chorus in The Corporation, as does Michael Moore — who also pops up in Orwell, with which his own movie shares the paranoid conceit that, if there is anything still to choose between George Bush’s America and the world of George Orwell’s 1984, the former is well on the way to transforming itself into the latter. The impression made upon anyone who does not share them of a tight-knit little gang of “progressives” who have all got together to reinforce each other’s delusions is overpowering.

The danger in any such enterprise is that the critical faculty is suspended. Take the nonsensical title of the Howard Zinn film, by Deb Ellis and Dennis Mueller, which is also the title of Professor Zinn’s own memoir. Why can’t you be neutral on a moving train? Or on a bus, airplane or ocean liner, for that matter? Somewhere in this muddled metaphor there is a vague sense that the train itself, if moving, cannot be in neutral — though even that is untrue if it is rolling down a hill — and therefore there must be some sense in which the same applies, or ought to apply, to its passengers — though of course people are not neutral (or non-neutral) in the sense that trains are anyway. There is nothing political or ideological about this rhetorical train-wreck, but it doesn’t occur to anyone involved to give it even such a tiny but obvious bit of editing as would be necessary to put it right. Why would Ellis and Mueller correct the professor’s title when they treat every other word out of his mouth as if it were holy writ?

Likewise, at one point in the film Zinn is quoted as saying that the phrase “collateral damage” is “the language of terrorism.” Of course it is precisely not the language of terrorism. To the terrorist, who targets civilians deliberately, no damage is collateral. Every shattered body is an achievement, the very thing he was aiming at in the first place, not an accidental by-product of some other purpose. “Collateral damage” is the language of the counter-terrorist, the soldier who wants to confine his killing only to the terrorist enemy, not just anyone who happens by at the wrong moment, but is not always able to do so. By all means, let the professor criticize such language for its bureaucratic callousness. Let him even make the case that collateral damage is too high a price to pay for combating the terrorist enemy militarily. But someone needs to tell him that he is talking through the back of his neck if he fails to make even so elementary a distinction as this between the methods and aims of the two sides.

Naturally, no one does. Nonsense unchecked by the higher critical faculties is everywhere in these four films — as, indeed, how else could you get from life in these United States, circa 2004, to the nightmare vision of totalitarianism in 1984? It is a good example of the way things work in Hollywood, which has never demanded much in the way of a critical sense from its creative talent but the dominance of whose culture did not, before Mr Moore came along, extend very far into the realm of the documentary. Assisted by a more general blurring of the distinction between fact and fiction evident in “reality” TV, it is now marketing these bogus documentaries as entertainment — and, we might add, entertainment as if it were documentary.

At least that is the way much of the anti-Bush media choose to regard movies like The Day After Tomorrow or The Manchurian Candidate. Fiction, in these picture only provides a license for the political speculation to go beyond outrageousness and into the realms of the fantastical. Or, as Frank Rich put it in The New York Times, “Freed from any obligations to fact, The Manchurian Candidate can play far dirtier than Fahrenheit 9/11.” Leaving to one side for the moment the fact that it is not possible to play much dirtier than Fahrenheit 9/11 — what worse thing than sending men to war in order to line his own pockets, and those of his family and friends, could anyone accuse a president of? — you’ve got to wonder at the gullibility of anyone prepared to take anything about The Manchurian Candidate seriously, even its “playing dirty.” Does he really suppose that Halliburton or some other big American corporation is kidnapping American soldiers, brainwashing them and training them as assassins of American elected officials? And if he does not, exactly what does such an allegation, made by the movie, stand for that is worthy of credit?

Here is Frank Rich. The movie, he says, “plays by the same nasty rules as the administration it attacks, stoking fear for partisan advantage by making the demagogues of fear almost as scary as the terrorists themselves.” And what, pray, have these “demagogues of fear” done to justify such an insinuation? Mr Rich himself gives us no clue, and nothing suggests itself unprompted. Could he be thinking of the WMD in Iraq? I suppose you could call that “stoking fear,” but it is begging the question to assume that it was done “for partisan advantage” and not because the president, along with every intelligence service in the world, thought that there was really something to be afraid of. Or is it the absurdities of Mr Ridge’s color-coded terror alerts that his near-homophonic namesake has in mind? There, partisan disadvantage would be more like it, since the administration looks more ridiculous every time it warns of an attack that does not come. Of course it continues to issue dud warnings because Mr Rich and others in the media have spent a largish portion of the time since 9/11 raking it over the coals for not doing enough fear-stoking in advance of that dreadful date.

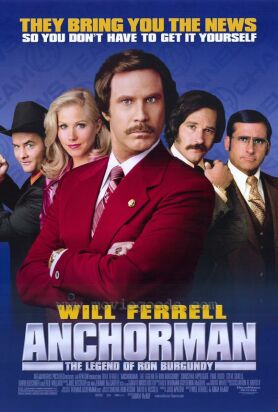

But the more outrageous the Michael Moores are the more outrageous the Frank Riches can be while still looking less extreme than that. Like everything else that Hollywood touches, politics becomes merely a matter of fashion, and anti-Bush chic is very much the rage this year. They don’t come any dumber than dumb movie stars, and every dumb movie star nowadays knows that Bush is a dummy. That’s what fashion is good for, after all: it allows the merely knowing to act as if they know something besides what everyone else is saying. Thus even Will Ferrell’s lame Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy cannot resist taking its own puny swipe at the Bush administration, noting that the dumb-as-a-brick character called Brick (Steve Carell) in its1970s San Diego newsroom went on to work as an adviser to the Bush administration.

Frank Rich also has something to say about this movie, which he considers “hilarious.” It shows, he thinks, why the major networks are in the White House’s pocket and are “not challenging a president as long as he’s riding high in the polls.” To have come through the last three years without noticing any challenges from the broadcast media to the president’s version of his response to terrorism might seem to some to argue a positively Brick-like stupidity. But we may be more charitable. Mr Rich is simply a dedicated follower of fashion whose tastes have been formed, like those of so many other enthusiasts of the popular culture, by too many summers of sheer fantasy.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.