Hoosier Heathen

From The American SpectatorThe movies have always sought a pretext for titillating their audience with images of sex and violence. In the old days, their excuse was moralism. The violence was overt while the sex was mostly implied — though the downward pressure exerted by celluloid imagery on standards of feminine modesty was always pretty constant — but both sex and violence were clearly marked as good and bad. The good was naturally celebrated and the bad execrated, especially after the introduction of the Hays Code in the early 1930s. But it was also the natural tendency of the medium to break down those carefully insisted-upon moral distinctions. Visually, of course, sex is just sex and violence is just violence, and this generic quality ultimately triumphed over the moralism. From the end of the Hays Code in the mid-1960s until very recently, film-makers have gloried in presenting us with sex and violence for their own sakes, not bothering themselves very much if at all about those troublesome moral questions whose consideration was a cost of doing business for their predecessors.

Lately, however, there have been signs that a re-moralization of sorts is underway, at least with respect to sex. Unlike the old moralism, this is not an attempt to distinguish between good and bad sex but rather between old and new morality. It’s not enough, now, for the new moralists that they have been liberated from the old constraints. At this distance of time the old constraints seem to have taken on a new and sinister quality in their eyes. That now-discarded moral model with its emphasis on chastity before marriage and fidelity afterwards was tainted not only by a religiously based assumption that sex was “dirty” and sinful but also by the values of the so-called “patriarchy” for whom a woman’s chastity, always more important than a man’s, was simply something that added value to patriarchal property. Of such disgusting attitudes, the theologians of sexual liberation feel it morally affirming to re-enact the defeat — as a kind of proof of their own superior virtue.

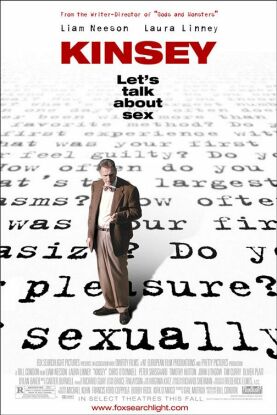

That at any rate is what is going on in Bill Condon’s Kinsey, a biopic about Professor Alfred Kinsey of Indiana University, the pioneer of sexual research of the 1940s and 1950s who did perhaps more than any other single person to de-moralize public attitudes to sex and so paved the way for the various sexual revolutions of the 1960s. As played by Liam Neeson, Professor Kinsey is clearly a hero of science and, only slightly less clearly, a hero of the moral and cultural revolution as well. At odd moments, Condon does hint that the de-coupling of sex from morality did have a few drawbacks in those early days, but they seem more like glitches needing to be ironed out, presumably by better technique, than anything permanently troubling. Certainly in comparison with the nastiness and unattractiveness of the “repression” that went before, the brief allusion to marital troubles among Dr Kinsey’s rather free-loving associates seem small matters.

Kinsey’s career, first as a world expert on the gall wasp — he was known as “Get-a-million” Kinsey by his colleagues for his indefatigability in collecting specimens — and subsequently as a sex researcher who used similarly exhaustive techniques, is played out here as a love story. His devotion to science is matched by his devotion to his wife, Clara “Mac” Macmillan Kinsey (Laura Linney). Their gloriously happy sex life is seen as the inspiration for Kinsey’s research interest. Brought up in a family headed by a strict and joyless evangelical lay preacher, played by John Lithgow, Kinsey had rebelled against most of his father’s principles but had remained sexually chaste until meeting and marrying Mac. Both of them were virgins when they married, and they required some advice and assistance from a doctor to get their sex lives started. Subsequently we see Kinsey picking up one of the marriage manuals of the time and pronouncing it to be “morality disguised as fact.”

Interestingly, the same could be said of his own work. Always he insisted that he wanted to free sex and the notionally pure sexual knowledge he sought from the obfuscations of morality, but of course in doing so he was introducing into the equation a new morality of his own — the one under whose sway we all still live. Having succeeded in his effort, as he puts it, “to strip away everything but the physiological,” he reintroduced morality in the guise of “what’s normal” and according to the maxim that “everybody’s sin is nobody’s sin.” The result was for Kinsey personally, it seems, what it also was for American and Western society under his influence, namely a freedom to gratify sexual desire that came to seem almost like an obligation. Thus when he experiments with homosexuality with one of his assistants (Peter Sarsgaard) he justifies the experience to Mac by referring to the desire as something “inside of me” which to deny, particularly for the sake of mere “convention and social constraint,” would be a form of “hypocrisy.”

Mac replies through her tears that “Maybe the social constraints are there to stop people from hurting each other,” but she later confesses that there were “some benefits” from the episode: “It certainly sparked things up sexually” between them, she says. So that’s all right then. She even takes her husband’s lover to bed herself to show how well she has learned his lesson. Meanwhile, the world outside this little Hoosier Eden is depicted as ridden with hypocrisy, racism, bigotry, religious fanaticism and anti-communist hysteria all of which, it is more than hinted, owes something to the emotional and sexual restraints from which Kinsey was even then freeing both himself and the world. The culmination of all this moral triumphalism comes near the end of the film when we see Kinsey conducting one of his endless series of interviews with an attractive middle aged lesbian played by Lynn Redgrave. Doubtful about the success of his work, he is reassured when she tells him that she had been on the point of despair and suicide when she had learned from him that she was — praise God! — normal. “You saved my life, doctor!” she tells him.

A touching story, no doubt and one which must make us all glad to have been born into the enlightened post-Kinsey era and not the dark ages which came before. A similar message is built into Mike Leigh’s Vera Drake, the Movie of the Month, but there is a curious difference between the two films. Whereas Condon has nothing but contempt for the prisoners of social constraint, Leigh approaches them with sympathy and even love. Perhaps this is because of his left-wing politics which would eschew the individualistic American view that the repressed have only themselves to blame for their sufferings. Certainly the upper-classes do not come out of the film looking very well, but even they are not depicted as being simply too stupid to know any better. We get the sense in this film, rare enough even in movies that set out to celebrate past events and people, that the differences between ourselves and our forebears are owing to some more interesting cause than the fact that we are simply smarter than they.

Set in grim, gloomy, post-war London in 1950 when war-time rationing was still in effect and ordinary people had to turn to the black market for basic necessities, the film presents us with a world in which everyone has a secret, from Sid (Daniel Mays), son of Vera (Imelda Staunton) and Stanley Drake (Phil Davis) who trades women’s nylon stockings for cigarettes to Susan (Sally Hawkins), the upper-class girl who, date-raped and impregnated, seeks the imprimatur of the medical profession on her “operation” — and to keep it hidden from her parents. For this she has to pay fifty times what the working class girls of the back alleys of north London pay for Vera’s services of a similar kind. Not that Vera herself charges for them. She performs abortions in the same spirit with which she looks after her aged mother and visiting neighbors in need of assistance. It is her friend Lily (Ruth Sheen) who puts her in touch with the girls “in trouble” and pockets the two guineas (£2.10 in the decimal currency) she charges them without Vera’s knowledge.

This makes Vera a saintly abortionist like Michael Caine’s character in The Cider House Rules — obviously, you would think, a set-up to demonstrate the benightedness of those who once made abortion illegal. And yet Leigh does not take the easy option of making Vera and Stan, ordinary working class folks as they are, into people morally ahead of their time. They themselves regard what Vera does as wrong, and yet they have learned — as people did learn in those days — to live with the contradiction. Doubtless this is what Alfred Kinsey and a great many others since his time would regard as “hypocrisy” — or that which La Rochefoucauld said long before we learned simply to loathe it was the homage that vice paid to virtue. I don’t know about you but I don’t see how it is an improvement to have, as we do in our enlightened and liberated times, all the same vices not bothering to pay any homage to virtue at all.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.