The Faith of a Critic

From Washington Post "Book World"

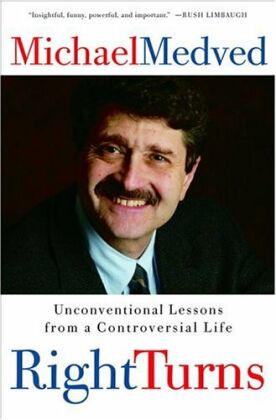

RIGHT TURNS

Unconventional Lessons From a Controversial Life

By Michael Medved. Crown Forum. 436 pp. $26.95

In his new autobiography, Michael Medved tells many stories about his transformation from liberal Democratic activist to conservative Republican media star, but none so unwittingly revealing as this one — which combines fat jokes, self-promotion and divine intervention.

Here’s the story: In writing The Hollywood Hall of Shame: The Most Expensive Flops in Movie History (1984), he and his brother and co-author, Harry Medved, deliberately included a section making fun of Elizabeth Taylor for her size as well as for the bad movies she had made. This was done in hopes of appealing to Joan Rivers, then the “permanent substitute host” for Johnny Carson on NBC’s “The Tonight Show” and pursuing what Medved calls ” a nasty and hilarious vendetta” against “the once svelte and sexy superstar.” Sure enough, he was invited on the show — but on the second night of Passover, when religious obligations made it impossible for him to appear.

He explained this to Bob Dolce, the show’s “legendary guest coordinator,” who invited him to do the show five nights later. Again Medved had to explain that traditional Jewish observance would not allow it. Dolce was a bit annoyed; some Jewish members of his staff had never heard of this later holiday, and Medved explained that, although many less observant Jews did not keep them, the two holy days at the end of Passover were as important as the two at the beginning.

“Bob sounded so dubious when he hung up the phone that I assumed I had obliterated, forever, any possibility of a Tonight Show appearance,” writes Medved. “Considering the horrific martyrdom (death, dismemberment, dispossession) my ancestors experienced for the sake of their faith, this small sacrifice seemed utterly insignificant, but it still left me feeling sour.” But — hallelujah! — legendary Bob called back with a third invitation, to which “after a quick glance at the calendar I shouted my grateful acceptance.” His appearance was a success, and the next day he received a telephone call from John Davies of WTTW, the PBS affiliate in Chicago, to offer him a tryout on the station’s movie-review show, “Sneak Previews.”

The rest, as they say, is history. Medved went on to do 12 years on the show with his co-host, Jeffrey Lyons, thereby receiving the kind of national media exposure that led to his fame and fortune — not only as a TV star but as a bestselling author and, today, a nationally syndicated radio talk-show host who works out of beautiful Seattle and has what can only be described — by himself, at any rate — as a perfect marriage and family. Through it all, he has “tried to avoid the solemn self-importance of so many of my fellow movie critics,” he writes, mentioning no names. It must have been particularly hard for him to stay humble when, six years after he began with “Sneak Previews,” John Davies told him that the only time he had watched “The Tonight Show” that whole year was that post-Passover night that Medved had been on.

Coincidence? He doesn’t think so. The mute example of those murdered, dismembered and dispossessed forebears does nothing to deter him from enjoying a “sense of an ordained destination” about his life’s path, or from using the word “providential” to describe making fat jokes on “The Tonight Show” at Elizabeth Taylor’s expense.

All of this contains more than a hint of parody, particularly in view of what I take to be the deliberate echo of the providential Calvinist narratives that, from the Puritan fathers to Cotton Mather to the American Revolution itself, were so central a part of America’s founding. There may also be another allusion to these stories in the organization of the book, which is laid out as a series of 35 moral, political and prudential “lessons” rather than mere chapters. Providence seems to have lowered its sights a bit since the old nation-building days if it’s now busying itself about getting better gigs for movie critics. Of course, as a movie critic myself, I may simply be envious because the Almighty has never arranged for me to have a TV show.

Still, if doubtful about his style, I found myself in agreement with much of the substance of what Medved writes. I admire his fervent patriotism and respect for the faith of others, and I share his disgust with the way religion and morality are often portrayed in the movies — though I cannot join in the Jewish Medved’s unlikely enthusiasm for Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ.”

Medved’s is an indispensable voice in America’s national dialogue on politics and popular culture. But for his next “lesson,” or his next book, I wish that he would learn the virtues of understatement, irony and a becoming sense of proportion about that culture and his own place in it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.