American Propaganda

From The American SpectatorAccustomed as I am to writing about the political cinema — and since Fahrenheit 9/11 it seems there is less and less of it that is not political — I am always amazed that people can’t see propaganda in a work of fiction even when it is as obvious as it is in Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby. To me this is as crude a piece of propaganda on behalf of assisted suicide as it is possible to imagine. None of the characters looks even remotely like anyone from what we still call, in spite of TV’s attempt to take it over completely, real life. All are designed solely for the purpose of getting poor Hilary Swank, playing essentially the same role she played in Boys Don’t Cry, to such a fever pitch of the pathetic that we can’t wait for Clint to put her (and us) out of her misery. And yet Clint and Hilary and their many apologists in the media are so insistent that the movie takes no position on assisted suicide that the Academy gave it an Oscar just to disprove the evidence of the feeblest political radar that it indeed propaganda.

There is no big mystery about why they would do that. Ever since the days of McCarthyism when movie people who were Communist party members or sympathizers tried to pretend that they were harmless entertainers, the cultural left in America has been heavily invested in similar kinds of camouflage. In particular, any complaints about its steady process of erosion and undermining of traditional religious values is invariably presented by a compliant media as a figment of right-wing paranoia. I might even venture to say that the evisceration of American education over the past 40 years has been deliberately undertaken in order to rob those who pass through it of the critical sense necessary to spot such propaganda — except that that would sound too much like right-wing paranoia. Anyway, there are plenty of other cultural phenomena to explain why that happened. Don’t get me started.

But, whatever the reason, American propaganda is undoubtedly the crudest, the most laughably obvious in the world. In Europe they did their own version of Million Dollar Baby, a Spanish movie by Alejandro Amenábar called Mar Adentro that came out at the same time and was such superior propaganda that it almost rose to the level of art. At least when Europeans are being brainwashed, they insist on its being done with a bit of style. Americans not only don’t see (or pretend they don’t see) propaganda when it pokes them in the eye, but they are also capable of seeing it where it doesn’t exist. When this happens it seems somehow even more depressing, since it makes what would otherwise seem mere unthinking philistinism take on a more sinister and ideological cast.

For example, Mike Leigh’s film, Vera Drake, another Oscar nominee (both for Mr Leigh as Best Director and Imelda Staunton as Best Actress) was picked up by some as a choice bit of “pro-choice” propaganda. “We have to make sure that on our watch, the clock doesn’t get turned back,” as Jatrice M. Gaiter, leader of Planned Parenthood of Washington, D.C. was quoted in The New York Times as saying. “This is a wake-up movie, a wake-up of consciousness to the stark reality that faces us.” No, Jatrice, if that is your real name, this is not a wake-up movie. It is a roll-over-and-go-back-to-sleep-and-dream-of-yesterday movie. Vera Drake almost miraculously cuts through decades of “wake-up” style propaganda to remind us, just for a moment, of a time when abortion was viewed with such horror, even by those who performed it, that its name could scarcely be mentioned.

Yet in vain was it for Mike Leigh to insist, in an interview with the Times reporter, that he had not intended his picture to be that kind of “abortion movie.” On the contrary, he had wanted the audience “to consider the moral issue of abortion” — something which would seem to require as a minimum condition that the audience see both sides of the question. That is of course the one thing that propaganda can never do. But so politicized has the culture become of late that the movie audience, in particular, seems at times to have got out in front of the movie-makers in the demand for one-sided, strident and artless propaganda. Don’t give us art! cry the liberal-minded masses. Don’t give us nuance, subtlety and intelligence! Give us the kind of mindless propaganda of which Michael Moore has become the premiere exponent. We are the rabble, after all. Rouse us!

And even if, like Mr Leigh, they resist this demand, their subtlety and intelligence will be treated as propaganda anyway. The issue is confused by the fact that there is propaganda in Vera Drake. It’s just not about abortion. It is, rather, the typical old-left class-war propaganda that you can find in most of Mike Leigh’s films. But this may be regarded as an artefact of the cinematic language he uses — something that is by now presumably so familiar to him that he doesn’t even know he’s doing it. Something similar can be said in defense of Clint Eastwood, I suppose. He has been making movies which purvey the same kind of sentimental guff — damaged and doomed innocence in juxtaposition with a posturing Byronic (or Greenean) hero (sometimes, as here, played by Clint himself) who dares damnation as an expression of his compassion — that he probably doesn’t even know he’s doing it anymore.

This is also true of the new documentarians, who have learned their cinematic language from Michael Moore. He in turn developed it out of the political documentaries of the 1970s, especially those like Hearts and Minds that were made to oppose the Vietnam War. This language has now become so common that it would be hard if not impossible to make documentaries, especially about war, in any other idiom. Or if one did, to have them picked up for distribution. In other words, if you tell a story in a certain way, it will automatically become anti-war propaganda, just as if you make a movie about abortion today it will automatically become pro-choice propaganda.

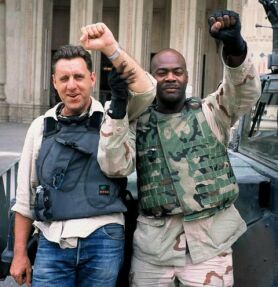

Consider the case of Gunner Palace by Michael Tucker and Petra Epperlein. This is a movie that was made with a great deal of sympathy for the soldiers of the 2/3 Field Artillery living in a Baghdad palace formerly belonging to Uday Hussein and going on dangerous patrols where they were not always entirely successful in avoiding such hazards as Improvised Explosive Devices, snipers, Rocket Propelled Grenades etc. There is, presumably, more than one way of telling the story of these men, but apparently there is only one way of telling it that fits with the acceptable cinematic idiom of our times. This can be summed up as follows:

(1) concentrate on the human and emotional lives of the soldiers rather than their mission, or any political or strategic considerations and

(2) always look especially for reactions to the deaths and injuries of comrades;

(3) never mention any actual or plausible reasons for the mission; if any reasons must be mentioned they should be bogus ones (e.g. WMDs);

(4) always stress the detachment of the soldiers’ commanders and, especially, the political leaders who sent them into harm’s way from any sense or understanding of the dangers they face and

(5) go prospecting for the cinematic gold of this genre, which is any expression of disillusionment on the part of the suffering soldiers.

Observe these rules and you can hardly reach any other conclusion than that of Gunner Palace — which, as it happens, is a quotation from a certain Sergeant Wilf, emblazoned on the screen: “If you see any politicians be sure to let them know that while they’re sitting around their dinner tables with their families talking about how hard the war is on them, we’re here under attack nearly 24 hours a day. Dodging RPGs and fighting not just for a better Iraq but just to stay alive.” The beauty part of this kind of thing is that any war, no matter how justified, no matter how successful, can when submitted to this treatment be made to look like the latest version of Vietnam, which first established the pattern. All soldiers are fighting to stay alive and most are ready to complain to a sympathetic listener about not being treated right by “politicians.” Our respect for their sacrifices must immediately stifle any impulse to gainsay them, or even to suggest that they might not be looking at the big picture. Gunner Palace will give you some idea of what it is like to be a soldier in Iraq today, but it is also an illustration of the unhappy fact that American movies are increasingly turning into propaganda without even knowing it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.