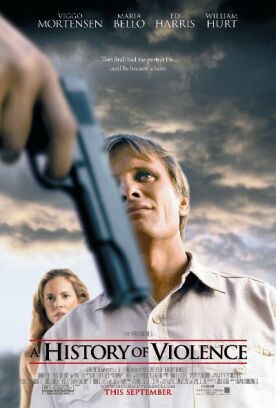

History of Violence, A

The best line in A History of Violence comes when William Hurt, playing a sinister mafia boss, berates a hapless underling who has just failed to strangle his, the boss’s brother, with the old Godfather-garotte trick: you know, the cord stretched tight between two hands and unexpectedly looped over the neck and across the wind-pipe from behind the head. “How do you f*** that up?” he screams at him. “How do you f*** that up?” And, receiving no answer, shoots him dead. We might almost say the same thing about the movie, which has a good story to tell which it tells very well for most of its length — until it falls a victim to its own portentousness and its belief in that great moral bogeyman of our times, “violence.” How do you f*** that up?

Let me explain. The whole concept of “violence” is flawed from the get-go, for it makes no distinction between legitimate and illegitimate force. The use of the word in this generic sense implies that the “violence” of the criminal is no different from the “violence” of the policeman who subdues him. Originally a Marxist idea, this worked its way into the mainstream beginning about fifty or sixty years ago, when people began to think it very clever and sophisticated to act as if there were no difference between the two things, or that the difference was only a matter of how “society” had distributed power between them. Since then, the idea of “violence” as generic and not in its original sense — related to “violate” — of criminal and illegitimate violence has steadily gained ground until it is now a commonplace of moral debate, in America as it is everywhere else in the Western world.

That is the real “history of violence” promised in the title. But David Cronenberg, who directed the film, and Josh Olson, who adapted it from a graphic novel by John Wagner and Vince Locke, don’t take their history that far back. They want you to think that that commonplace and its fashionable liberal corollary, America’s unique propensity to “violence,” was there from the beginning. In fact, the idea itself is really very recent and depends on the intellectual sleight-of-hand mentioned above: the weasel-word, “violence.” As a result, Cronenberg mystifies the whole subject by taking the view that acts of violence, irrespective of their context or justification, leave a permanent moral taint on those who commit them, though they are also a permanent temptation — both to the violent themselves and to those who are attracted to their power.

Viggo Mortensen plays Tom Stall, who runs a diner in a small Indiana town. He is happily married to Edie (Maria Bello), has two attractive children and is popular in town. One day, two very bad bad guys (we have already been introduced to their methods) walk into his diner at the close of the day and stick him up. He knows at once what we already know, namely that these are not men who are planning to leave any witnesses of their crime. As one of them is about to kill his waitress, just to show that they mean business, and the other is covering him with a gun, Tom smashes the carafe full of hot coffee over the head of the one in front of him, vaults the counter, seizes his gun and shoots the other dead. As he turns back to the coffee-covered one, he is stabbed in the foot, but blows him away too. It is a striking scene and very well choreographed.

All at once, Tom is a hero. He is on the TV news, not only in Indiana but nationwide. “How did it feel when you saw the gun of this deadly killer pointed at you?” asks the breathless TV reporter.

“Not very good,” replies Tom.

“An American hero and a man of few words,” she says to the camera and then, when it is off her, “I guess that’s all we’re going to get”

But the next day three more sinister men turn up in an expensive out-of-state car and start following Tom around. Their leader, Carl Fogarty (Ed Harris), calls him “Joey.” They know him from Philadelphia, says Fogarty, where they were once in the underworld together and “Joey” had badly injured him, Fogarty, with barbed wire, taking away the sight of one eye. Now Fogarty is seeking vengeance on this “Joey,” as he makes clear, though Tom keeps insisting that he is not Joey but Tom and has never been to Philadelphia. Meanwhile, Tom’s teenage son, Jack (Ashton Holmes), is being mercilessly bullied at school. Perhaps inspired by his father’s example in being proclaimed a hero, he finally fights back against the bully — and puts him in the hospital. Naturally, the school treats him as the aggressor and sends him home. Tom, like any responsible parent these days, takes him to task. “In this family, we do not solve our problems by hitting people,” he says.

“No,” replies the boy. “In this family we shoot them” — whereupon his father strikes him!

It’s a hilarious illustration of the sort of hypocrisies that naturally arise from the film’s view of “violence” — which is also that of the therapeutic culture that increasingly dominates our educational and legal systems. But, presumably not understanding the conceptual flaw in that view, Cronenberg takes it instead as deeply significant and a further instance of his banal moral, namely that violence begets violence. Well, perhaps you can see where he’s going with that, so I won’t have to give away important plot details of what happens later. As I say, it’s a good story, but it only takes on meaning if you can bring yourself to believe the frankly unbelievable proposition that forcefully defending yourself makes you a thug.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.