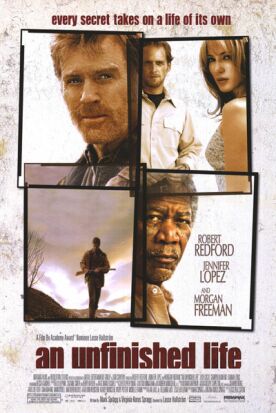

Unfinished Life, An

The tell-tale moment in An Unfinished Life, Lasse Hallström’s latest essay in liberal uplift, comes when Robert Redford, in the role of the emotionally-damaged old Wyoming rancher, Einar Gilkyson, reproves his 11-year-old grand-daughter, Griff (Becca Gardner), to whom he has only recently been introduced, for rudeness. “I expect you to be pleasant to whoever comes to my door,” he tells her — “unless it’s some guy trying to sell his angle on God. There’s no excuse for that bulls***.” The sentiment is of course no surprise from the director of Chocolat (2000) and The Cider House Rules (1999), but there seems to be not so much as a flicker of self-irony of the sort that might have been expected from some guy who is himself trying to sell to the movie-going public his angle on God.

But Mr Hallström, a Swedish director who has been working in America for the last decade and a half, also has the typical liberal take on theology as something that only conservatives and reactionaries do. His own God, revealed in the final scene as a disembodied point of view with the voice of Morgan Freeman — an actor who has lately made something of a career out of playing God or God-like figures — presumably strikes him as being quite uncontroversial. About that, anyway, he is surely right. The God of the Bible, if anyone took Him seriously anymore, would undoubtedly bring down the wrath of the popular and media culture upon His “judgmental” head. But the gentle, non-threatening, non-judgmental, Morgan-Freeman-god with his easy indulgence of human failings and feelings goes down so easily that you hardly even know he’s a god.

Like all liberal gods, he is very much pro-compassion and anti-guilt, and so this is a film about the purging of guilt and forgiveness. Einar is feeling guilty because he got so drunk, a year or so ago, that he was unable to rescue his best friend, Mitch, the character played by Mr Freeman, from a mauling by a grizzly bear. Now, pretty grizzly himself and perpetually unshaven, though officially off the sauce, Einar tenderly cares for Mitch, who is making a slow recovery from his injuries, by giving him daily morphine jabs in his hinder parts. Einar got drunk, as was his habit at the time, because he was grief-stricken about the death of his son in a car accident, for which he holds his estranged daughter-in-law, Jean (Jennifer Lopez), responsible. She had been driving the car and fallen asleep at the wheel. His inability to forgive her is a reflection of his inability to forgive himself.

Mitch, ever the voice of divine wisdom, tells him: “They call them accidents because they’re nobody’s fault.”

Stubborn Einar replies: “They call them accidents to make the guilty feel better.”

But when Jean gets beaten up by her latest boyfriend, Gary (Damian Lewis), and flees back to Einar because she has nowhere else to go, it becomes obvious that Morgan-God’s is the view that must prevail. Jean will persuade Einar that she feels even more guilty than he does — which is why, after all, she picks abusive boyfriends — and they will have to forgive each other and themselves. God’s forgiveness is of course taken as read. Even the bear is forgiven. “We walked into his business,” says wise old Mitch. “He was just doing what bears do. We can’t punish him for that.” He insists that Einar and Griff steal the bear from the cage where he is currently on display as a tourist attraction and release him back into the wild.

Only Gary remains unforgiven and is left to dwell forever in the liberal outer darkness reserved for Nazis, racists, sexists, homophobes and men who strike women — because easy villainy is a natural corollary of easy uplift. He also provides the occasion for Grandpa Redford to show us that his compassion can still be of the two-fisted variety. And what Gary is on the negative side, Griff is on the positive side. The former is an uncomplicated monster who brings out Einar’s latent sense of chivalry; the latter is an uncomplicated cutie-pie who melts the old man’s heart and makes him let go of his anger towards her mother. When Griff spoils Einar’s plan to free the bear and nearly gets him killed by putting his pick-up in neutral, she apologizes by saying: “I hit the gearshift. I didn’t mean to.”

“It wasn’t your fault,” says the now-enlightened Einar. “It was an accident.”

As the fractured family comes together again, they are joined by Josh Lucas as the hunky local sheriff, Crane Curtis, since the abused widow Jean obviously has certain needs. When Griff, who is initially hostile to Crane, becomes reconciled to him, the artificial family group, to which Mr Hallström also showed his partiality in Cider House Rules, is complete, and Mr Redford and Mr Freeman get round to their theological discussion.

“Do you think the dead care about our life?” asks Einar.

“Yes I do,” Mitch replies. “I think they forgive us our sins. I think it’s even easy for them.” And then he tells him of one of his dreams, as he has done throughout the film. He dreamt that he was flying, he says — “flying to where the blue meets the black, to where there’s a reason for everything.”

And here I confess to a catch in my own throat and a weakening, like Einar’s, of the judgmental impulse. For bad and cheap and facile as much of the picture is, when it comes to the final judgment, we all must hope that God will turn out to be a liberal and give precedence to compassion over justice.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.