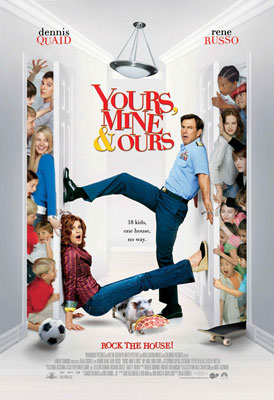

Yours, Mine and Ours

Yours, Mine and Ours (1968) originally starred Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda — both at least 15 years too old for the parts of a widow and widower who marry and amalgamate their already large families into a supersized one. In the end the then-57-year-old Miss Ball is supposed to be giving birth to the couple’s 19th child while the 63-year-old Mr Fonda gives what is meant to be an inspiring pep talk to one of his teenage step-daughters on the beauties of sexual continence and married love — “It isn’t going to bed with a man that proves you’re in love with him,” he tells her, “it’s getting up in the morning and facing the drab, miserable, wonderful everyday world with him that counts” — after the girl has asked him whether or not it would be right to yield to her boyfriend’s importunities and sleep with him Hey, it could happen!

At the time, that moral environment already looked a world away from 1964 when the memoir by Helen North Beardsley on which the film was based was published. From the point of view of 2005, it looks even more alien. But Hollywood can always find a way to stamp such ancient properties with the authentic vulgarity of our own time, and the remake, directed by Raja Gosnell and starring the slightly more age-appropriate Dennis Quaid and Rene Russo, takes out the moralism of the original, leaving nothing but an odd-couple yarn for the pre-teens, for whom the repetitive slapstick routines, mostly at Mr Quaid’s expense, are obviously intended.

In 1968, of course, grown-ups still went to the movies in sufficient numbers to induce film-makers to make movies about adult problems, even if they made them badly. Now that the market has become so kid-centered, so have the movies. Like the re-make of Cheaper by the Dozen a couple of years ago — of which, God help us, there is to be a sequel in a few weeks — this one takes a heart-warming affirmation of family values and turns it into a lesson to the parental authority figures to put their own lives second and give their spoiled brood even more of what they want. Just like Steve Martin in Cheaper, dad has to give up his dream job because the kids don’t think he’s paying enough attention to them.

Also, dad’s dream job is Commandant of the Coast Guard. That makes another interesting contrast with 1968, when Mr Fonda’s character was only a humble warrant officer in the navy but never considered — or would have been able to consider — giving it up. It’s another measure of the extent to which Hollywood these days is making more and more movies about eminent personages, often celebrities and rich people, rather than ordinary folks. The amalgamated Beardsley clan may be over-populated, but there isn’t so much as a hint of poverty or hardship, as everybody fits nicely into a converted lighthouse in a picturesque setting on the coast of Long Island Sound and all learn teamwork (or don’t learn it, actually) by sailing daddy’s yacht — appropriately named My Way. As long as you’re pandering to kiddies’ fantasies, you might as well do the job right.

In 1968 the mostly negligible plot centered around Mr Fonda’s attempt to adopt his new wife’s children as his own, something that also looks more than a little strange by our standards, especially when one of the littler children is supposed to be desperate to take his new father’s name. In 2005, the story concerns a conspiracy among the children of both families, who don’t like each other, to break up their parents’ marriage. Charming, don’t you think? The reasons why they don’t like each other are also instructive. Mr Quaid is, as we might expect of a Coast Guard admiral a red-state sort of guy who likes to run a tight ship. Miss Russo, by contrast, is an arty, hippyish, blue-state type with a rainbow coalition of adoptees and her own kids, all of whom are allowed to run wild. They call their new step-siblings “evil preppies.”

“You sound like a big military robot, Frank,” says Helen in one of the fights provoked by the children.

“Yeah?” replies Frank. “Well you sound like a big free-to-be-you-and-me flake!”

You’ll scarcely credit it, but Frank even believes in spanking. Just a little bit, you understand, but his shame is palpable when the kids reveal the fact to his disapproving wife. (Miss Ball’s first appearance in the role of parent in 1968, by the way, is as she is spanking one of her children.) Helen’s motto, you might not be surprised to learn, is “Spanking is never the answer,” and it carries the day. You can hardly suppose that Frank and Helen didn’t talk about being at opposite ends of the cultural divide before they married, but their only discovering it afterwards gives Mr Gosnell the opportunity to show the conservative capitulating to the child-centered views of his wife — and of the film-makers, who thus complement the kiddie-fantasy with one of their own: namely, that of the whole country united under the rule of parental and cultural laissez-faire. If that vision appeals to you, then you might like this movie. But then, if that vision appeals to you, you are probably either a child or a Hollywood film-maker.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.