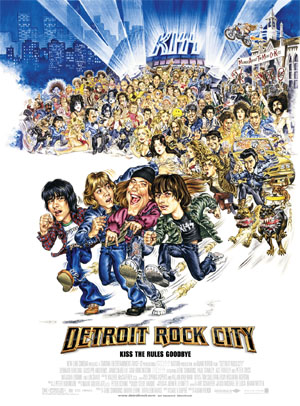

Detroit Rock City

Detroit Rock City, written by Carl V. Dupré and directed by

Adam Rifkin, is a loathsome movie about which I have nothing more to say than to

marvel that anything like it could be made today. There is a lot that is wrong

about the movies of our own time, but to give them their due they are rarely as

mindless in their subservience to the values of youth culture as the movies of

the late 1960s and the 1970s. Nor, for that matter, is the youth culture itself

so mindlessly committed to mere self-indulgence dressed up as principled

“rebellion” as was the Hollywood of Easy Rider and its decade-long trail

of imitators. But here is a movie which almost has the look of having been made

at the time when it was set—to wit, the late 1970s at the height of the

fame of the rock group Kiss, the members of which appear in cameos as

themselves.

And with them they seem to have brought back that 1970s combination of

narcissism, boorishness and anarchic self-righteousness that we associate with

the belated hippies of the period and their brain-fried enthusiasm for rock

stars who played deafeningly loudly and with a certain destructive energy but

without the least musicality. Four high school boys from Cleveland (Edward

Furlong, Giuseppe Andrews, Sam Huntington and James De Bello) drive to Detroit

to attend a Kiss concert and have what are meant to be comic adventures along

the way. They are not comic. A confrontation on the road with some

Travolta-imitating, disco-loving “Guidos” is as nasty as it is tasteless and

offensive and ends with the Kiss boys beating up the disco boys and wrecking

their car. It’s a real riot.

Likewise, the portrait of one of the boys’ blue-nosed, religious-nut of a

mother (she says that KISS stands for “Knights in Satan’s Service”) is utterly

without irony or plausibility, a particularly self-absorbed teenager’s

caricature of adult authority. And I would have thought that, twenty years later

at least, a movie which celebrates the stage artistry of Kiss might be a little

more careful about ridiculing the kitschiness of Barry Manilow or The

Carpenters, mom’s favorite musicians. Two members of the Roman Catholic clergy

are also dragged in, presumably for satirical purposes, though the satire

consists in the one case of silliness induced by eating a pizza laced with

hallucinogens and in the other of a prurient interest in one of the boys’

confessions of sexual sin—a sin which actually takes place in the

confessional.

Such stuff amounts to the kind of self-conscious naughtiness, misidentified

with “rebellion,” that appealed to some kids in the 1970s, though it is hard to

imagine that teenagers today will find it something they can “relate to.” At any

rate, if they do it will mean that the 70s are come again and we might as well

sell the whole country to the Chinese and throw ourselves a big farewell party.

I suspect that the movie’s intended audience is really the 70s kids—all

too many of them, alas—who never did quite manage to grow up after

experiences like these. But watch the box office returns among the prime

movie-going demographic of high school boys. If they like it, we’re going to be

in for a rough ride in the new millennium.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.