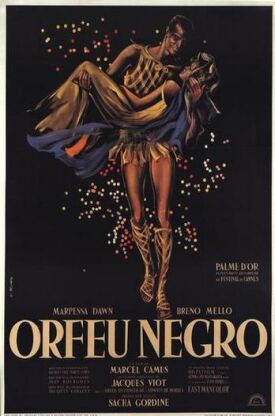

Black Orpheus (Orfeu Negro)

Near the end of Black Orpheus (Orfeu Negro), Marcel Camus’s masterpiece of 1959, there comes what can only be described as an authorial disclaimer that strikes the film’s one seriously false note. “The happiness of the poor is the great illusion of Carnival,” we are told, more or less out of the blue. Up until that point, I think it would hardly occur to most people to describe what they have seen as an illustration of “the happiness of the poor.” But there may have been political reasons why Camus had to stick this in, lest the prevailing left-wing culture of France’s cultural élite should have been shocked by a depiction of Third World poor people who are not both obviously miserable and aware of — and resentful about — their misery.

For the rest of us, the film is a retelling of the tragic classical legend of Orpheus and Eurydice, but set during Carnival time in Rio. This Orfeo (Breno Mello) is a tram conductor who, in his spare time, is a leading light of the Babilonia Samba School, one of several such institutions that compete for prizes at Carnival time, and is widely known for his dancing as well as his singing and guitar playing. In fact, it is said by the two hero-worshipping boys who follow him around, Benedito (Jorge Dos Santos) and Zeca (Aurino Cassiano), that Orfeo can make the sun rise with his music. The film’s famous theme song by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Luiz Bonfá, though very much understated here as first Orfeo and then one of the boys picks it out on his guitar, has been making the sun rise ever since.

Orfeo is also known as a womanizer, and his latest conquest, the fiery Mira (Lourdes de Oliveira), is determined to make him marry her, even if it means that she has to buy the ring herself. Easy-going Orfeo agrees to marry her. But just before Carnival-time, Eurydice (Marpessa Dawn) comes up to Rio from the country, where she has been terrified by the vision of a man she says wants to kill her. She means to stay with her cousin, Serafina (Léa Garcia), a friend and neighbor of Orfeo’s. Orfeo falls for Eurydice, and Mira becomes frantic with jealousy, threatening to kill her rival. Meanwhile, a costumed figure meant to represent death begins hanging around Eurydice as the Carnival festivities get underway. Naturally, she is terrified. Orfeo tries to soothe her, telling her: “I will protect you for ever, against everything. You will never be scared again. Never,” and they declare their love.

But the urgency of Orfeo’s wish to protect her itself seems to portend the impossibility of his doing so. Serafina, who is to play the Queen of Night to Mira’s Queen of Day in Orfeo’s samba, urges Eurydice to put on her costume and dance in her stead — a way of hiding from Mira, as well as Death. Serafina even has her own boyfriend, Chico (Waldemar De Souza), kiss her cousin to lend plausibility to the disguise. But Mira discovers the truth and, while Orfeo is dancing in his golden, sun-symbolizing costume, chases Eurydice through the streets of Rio, which are teeming with revellers. Soon, Death takes up the pursuit and follows Eurydice to the now-deserted tram terminus, whose sinister machinery is meant to make it stand in for the classical underworld.

In the legend, it will be remembered, Orpheus descends to Hades and so charms the infernal powers with this music that he is allowed to lead Eurydice back up to the light — provided that he doesn’t turn around to look at her as she follows him. Of course he does so, and she is condemned to return to the shades beneath the earth. It doesn’t quite work like that with our Orfeo — though he’s got a guide to the underworld in the form of an ancient janitor at the Bureau of Missing Persons, and a dog called Cerberus guards the approach to a cigar-smoking witch-doctor, who attempts to conjure up the spirit world with a wilder version of the universal dance, laced with bits of voodoo or santeria-like ceremony. This is a reminder of the origins of the samba in West African rituals brought to Brazil by slaves.

Camus, who never did anything remotely as good again, is a committed realist, possibly for political reasons, who is obviously made a little nervous by the magic and spirit-conjuring — as he also is by the thought that he might be supposed to be insufficiently aware of or sympathetic towards the sufferings of the poor. But the result of this hesitancy with his materials, whether intentional or not, is to add to the sense of the seductiveness and danger of the dance and the music and the spectacular cliff-top scenery of Rio, as if the director himself were afraid of being drawn too far into his own vision.

In other words, the effect of telling us that the poor of Rio are not happy, even at Carnival time, is to make us afraid that they really are happy — or at least that they swim like fish in the sea of their unhappiness and so don’t recognize it as unhappiness but simply as their element. That way madness lies, of course, at least for political rationalists of the left. But the seductions of the samba here that have captivated audiences for going on half a century are made the more compelling for seeming — as perhaps they are — more of a rationalist than a Christian heresy.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.