Our Brand is Crisis

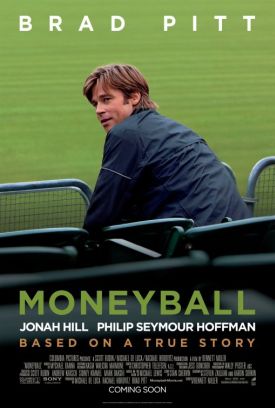

Goni in happier times

The subtext of Our Brand is Crisis, a riveting documentary by Rachel Boynton about the American political consultants who helped elect Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, popularly known as Goni, as president of Bolivia in 2002 goes something like this. American-style political campaigns in which candidates are marketed like soap or hamburgers are inherently corrupt in themselves and, when imposed upon a Third World country like Bolivia, a form of American imperialism. Leaving the substance of these contentions to one side for the moment, we may notice that they depend absolutely on what happened to Goni’s presidency in the aftermath of the election. If his presidency had been as successful — and in other circumstances it easily might have been — as his campaign, this film could not have been made.

The point is that its failure had nothing whatsoever to do with the clever marketing strategies of James Carville, Tad Devine and Jeremy Rosner of the Greenberg, Carville, Shrum consultancy in Washington that won the election campaign for him. Their success was owing to a carefully focus-group tested advertising campaign designed to split the anti-Goni vote — which everyone agreed was a substantial majority of the electorate — between the populist Evo Morales and the Latin strongman-type, Manfred Reyes Villa, who was the early favorite. This they did by concentrating their fire on Sr Reyes Villa by stressing his military background and hinting at corruption in the amassing of his personal fortune. Of course, this strategy could not have succeeded without the peculiarity of the Bolivian electoral system, which allows the winner of a plurality in a multi-candidate race to take home all the marbles, even though he wins (as in this case) with only 22 per cent of the vote.

So maybe the blame for Goni’s disastrous presidency should be laid at the door of whomever designed the Bolivian constitution rather than Mr Carville and Co?

Anyway, Ms Boynton’s own success in making a very taut, vérité-style campaign thriller — at least for political junkies — has nothing to do with her attempt, unsuccessful in my view, to add significance to the story by clucking her tongue about the evils of political marketing. To her credit, she herself makes it clear that Goni’s spectacular failure was unconnected to the campaign. Instead it was owing to his politically ill-judged decisions to raise taxes on the poor and to export Bolivia’s gas through a Chilean port. Above all, it was made inevitable by the machinations of the nasty demagogue, Evo Morales, in whipping up the popular paranoia directed against America in general and Goni’s American accent and connections in particular. This rabble-rousing clearly had a lot to do with the deadly riots which caused the president’s resignation and flight to the US only 14 months after his election.

Granted, the American-style manipulation of public opinion is not a pretty sight, but it is the way democratic politics works, more or less, the world over. The old aphorism about sausages and politics being the two things you don’t want to see being made inevitably comes to mind. But the really ugly — and, by the way, violent and anti-democratic as well as anti-American — campaign is that of Sr. Morales, representative of the Bolivian coca growers and now the newly-elected president of his country. Making that point, however, is no part of Ms Boynton’s purpose. Presumably it has no resonance with the American cinema audience, which has come to expect the Americans in these situations always to be the bad guys. Like the political consultants she so harshly criticizes, therefore, she’s only telling her audience what it likes to hear.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.