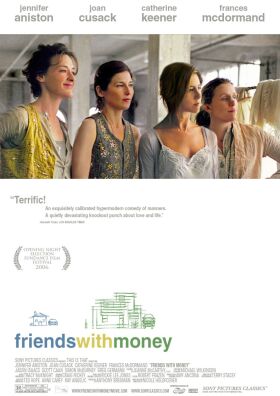

Friends With Money

Friends With Money, the new film by Nicole Holofcener (Walking and Talking, Lovely & Amazing) is a bit like Robert Altman’s Short Cuts in being a collection of separate but intertwined stories set in contemporary Los Angeles, but it is much cosier. This is not only because there are fewer stories and they are more closely intertwined, but also because the stories all center around their subjects’ domestic lives — or the point at which their domestic lives intersect with their more or less uncertain sense of who they really are. Lurking beneath this persistently unstable sense of self, particularly on the part of the film’s women, lies something of the feminist fear of loss of identity by taking on one’s husband’s — which is one theme that links the film with Ms Holofcener’s earlier work.

Christine (Catherine Keener) and David (Jason Isaacs), for example, are married screenwriters collaborating on a script about a bickering couple. As they write by role-playing, reading the parts to each other, it is unclear where their characters stop and they begin. The tensions between them are exacerbated by David’s need to dominate — and the fact that they have not been sexually intimate for a year. Christine seems to be expected — and to expect herself — to shoulder a share of the blame for this marital breakdown, but it is more likely that David’s overbearing self-sufficiency must compensate for his dependency on her in their intellectual collaboration by refusing her any of the physical kind.

In addition to Christine and David’s, we have the stories of Jane (Frances McDormand) and Aaron (Simon McBurney) and Franny (Joan Cusack) and Matt (Greg Germann). The three couples, all friends, all apparently prosperous and well-established, have adopted as a kind of mascot the impecunious Olivia (Jennifer Aniston), who has quit her job as a school-teacher and gone to work cleaning up after well-to-do people like her friends. The others make it their project to fix what they see as the broken life of sweet but spacey Olivia. She is “not married, a pot-head, working as a maid” — and, as we also learn, still pursuing a married lover who has broken it off with her. When a sad-sack of a would-be employer (Bob Stephenson) persuades her to reduce her already-low price for cleaning his shambles of an apartment, she says: “If he’s so pathetic he has to haggle with the cleaning lady, he’s worse off than me.”

Franny, the friend with the most money, arranges a date for Olivia with her personal trainer, a boor named Mike (Scott Caan), who is so oafish when they meet that Olivia asks him: “Are you stupid?”

Mike thinks for a moment. “Kind of,” he says disarmingly.

That she not only settles for this clod but takes him along with her on her cleaning jobs, consents to sex with him in her employers’ beds — sometimes while she dons a sexy maid’s uniform to gratify his fantasies — and gives him a share of her earnings in return for his merely notional “help” is meant to suggest that she suffers from “self-esteem” problems. To me that strikes a slightly false note. The author is trying to explain Olivia to us instead of just letting her be Olivia. Her over-imagined psychological complications are not necessary to account for such fecklessness and sluttishness.

There are other ways, too, in which we get the annoying sense that Ms Holofcener is trying to prove a point, or proffer an unneeded explanation of her characters’ foibles. The much-too tightly wound and competitive Jane, for instance, seems to be suffering from undiagnosed clinical depression. Meanwhile, everyone but Jane herself imagines that her easy-going and slightly effeminate husband Aaron is gay. When he meets someone so much like himself that he is also called Aaron (Ty Burrell) and they become friends, we think we know what will ensue. Except that it doesn’t. As the two Aarons enjoy a much too nourishing and well-presented lunch alone together while the wives are at work, one says to the other: “Just because you care about what you wear, it doesn’t mean you’re gay.”

“Absolutely!” agrees the other enthusiastically. “I love your shirt, by the way.”

And so another stereotype bites the dust.

There’s nothing wrong with busting stereotypes, of course, but I rather resent being made to feel that the stereotypes are only there in the first place in order to be busted by someone with an agenda in busting them. There is more subtlety and much more humor here than in the barely-disguised political tracts of John Sayles, for example, but at times we have the same sense that we have all the time in his films: the sense of being preached at. Fortunately, it is infrequent enough that it doesn’t interfere with most of what there is to be enjoyed here. People worry about growing old or unattractive; they get divorced or have problems finding a direction for their lives, but their various stories are never quite reduced to the level of soap opera. They are just real enough, and funny enough, for that.

Especially impressive is the way in which Ms Holofcener manages to hold in equilibrium the opposed forces of self-satisfaction and desperate anxiety in her characters, and so gently to satirize them without ever losing our sympathy for them. This feat is nicely summed up in the toast offered by one of them at a charity dinner on behalf of Lou Gehrig’s disease, or ALS: “To the fact that we don’t have ALS — or anything horrible.”

“Yet,” mutters Aaron.

Like its characters, the film is rather full of itself but, also like them, it is never less than enjoyable.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.