Finding it in a Movie

From The American SpectatorThe movies have always had a special appeal to adolescents. This is partly because their images of adult life have taught generations of young people, who have been ghettoized in high schools for the last century or so, how to behave in the more or less remote world of grown-up people, but mainly it is because of sex. The movies were made for that perennial adolescent obsession, just as sex was made for the movies. A quasi-pornographic appeal was implicit from the very beginnings of movie-glamour. Romance presented in a high-gloss, artificial, larger-than-life form has always given kids, as it has been intended to give them, the illusion of partaking of forbidden knowledge even when the bodies have remained covered. And of course since the 1960s when, not-coincidentally, censorship (including self-censorship) effectively ended and youth culture effectively became culture tout court, the appeal of celluloid to the young has only increased — as has the importance of movie-going in our ever-more-youthful courtship rituals. The title of Pauline Kael’s collection of criticism of 1965, I Lost it At the Movies, slyly reminded us of the extent to which young people had already learned to expect that sexual theory and practice would go together.

A conventionally moralizing approach to this state of affairs might lament the “loss of innocence” of childhood, and I wouldn’t want to deny that such a loss is real. But it is also true that movie-experience should not be mistaken for real experience. In fact, innocence itself really needs to be redefined to mean not the absence of knowledge but the absence of knowledge masked by its illusion. Hence the importance of “attitude” in popular culture. Attitude is the pretense of knowledge without its substance, a cheap cynicism that also goes under the name of “cool” or “hip” and that is meant to reassure those who adopt it of their superiority to mere experience. In their own conceit, life has nothing to teach the hip that they have not already learned from movies and TV, or perhaps from the faux profundities, the maudlin and self-pitying poetry of popular music. This illusion of knowledge can become very powerful indeed, as it obviously did in the case of the novelist Walter Kirn, whose recent review in the New York Times Book Review of a serious work of social and political philosophy, Harvey Mansfield’s Manliness, criticized it for not being “hip.”

It is not many years since such imbecility in such a place would have beggared belief, but now it passes almost unremarked. Surely at least a part of the reason must be the flattery so assiduously paid by the movies over the years to the hipness of the young, who have made up an increasing proportion of the movie audience in America. Among the latest examples of this flattery is Brick, by Rian Johnson, a movie which reimagines a typical film noir scenario and relocates it from the mean streets of LA to a prosperous suburban high school in San Clemente. Brendan (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is a student who, apparently, never has to go to class. Not only does the school, represented by Assistant Vice Principal Trueman (Richard Roundtree), not require it of him, but his world-weary worldly wisdom, fairly dripping with attitude, quite obviously has nothing to learn from any teacher — or, indeed, the adult world generally. When Brendan’s ex-girlfriend, Emily (Emilie de Ravin), appeals to him for help and two days later turns up dead, he becomes the classic noir detective, seeking a solution to the mystery of her death as his lonely, eccentric homage to her memory. This involves picking his way through a sleazy underworld populated by a collection of drug-dealers, junkies, thieves, murderers and whores, none of whom has yet achieved his or her majority.

Like that of the fatally unhip philosopher, the very idea would once have been ludicrous. In fact, it was deliberately so back in 1976 when Alan Parker dressed up children as Prohibition-era gangsters and had them shoot Tommy guns filled with ice cream at each other in Bugsy Malone. More recently, Roger Kumble translated the beau monde of pre-revolutionary France as detailed in Les Liaisons Dangereuse by Choderlos de Laclos into an exclusive Manhattan private school in Cruel Intentions. But by that time, 1999, no one was laughing. As a movie-going culture, at any rate, we were only too ready to believe that contemporary American teenagers could be the equals of Laclos’s 18th century French aristocrats in unprincipled guile, cunning, subtlety and cruelty — to say nothing of their being jaded with sexual experience. The idea is itself so naïve as to suggest that a surviving species of innocence is still alive and well and living incognito in Hollywood under the name of “hip.”

Fortunately, in odd holes and corners of the movie business, it is still possible to find more believable representations of young people — at least young people experienced enough to have got past their childish aspirations to hipness. One such is Steve Buscemi’s Lonesome Jim, about a couple of 20-something brothers still living at home called Jim and Tim, played by Casey Affleck and Kevin Corrigan, who see themselves with some justification as failures but who go on to vie with each other as to which of them feels the more acutely the fatal sense of misery and despair that they share. At first, the movie seems to take seriously its heroes’ self-pity and youthful contempt for their doting and relentlessly upbeat mother, played by Mary Kay Place. But gradually we are led to see — as one of the brothers is too — the absurdity of such posturing and emotional self-absorption, and the power of love to break through it. In acknowledging and appreciating for the first time his mother’s love, this boy learns how to love another woman, a new girlfriend and single mother named Anika (Liv Tyler), and so puts himself on the way to becoming a man. Harvey Mansfield understands the theory, but all save the hip ought to be able to understand the practice.

Brighton Rock

, Graham Greene’s novel of 1938 about a prematurely-aged teenage gangster called Pinkie, describes its hero as knowing “everything in theory and nothing in practice,” and the description is an apt one of such young people. Jim is a failed writer who doesn’t even notice that he has learned his despair along with his craft, such as it is, from suicidal models like Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf. Like so many other young people from comfortable backgrounds nowadays, he is tempted to despair before he has got anything much to despair about — perhaps because despair is hip. When Anika plasters a cut-out photo of a giant grinning mouth over Hemingway’s dourly bearded lips on Jim’s wall-poster, which dominates his bedroom, it is a cathartic moment. Suddenly, genuine feeling is wrenched free of the imprisoning “attitude” that has hitherto held it hostage, and the innocence that pretends to greater knowledge than it can possibly possess is dissolved in healing experience. The irony of such a reversal of conventional expectation could have been better pointed up by Mr Buscemi and his young and presumably autobiographical screenwriter, James C. Strouse, but it is there for the wise to see anyway.

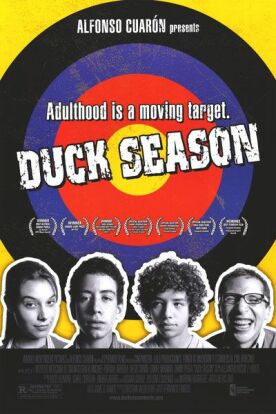

Even more touching to me, at least, is the traditional view of innocence and experience in Duck Season (Temporada de patos) by the Mexican director, Fernando Eimbcke. Two 14-year-old boys, Moko (Diego Cataño) and Flama (Daniel Miranda), are left alone one Sunday in the high rise apartment in Mexico City belonging to Flama’s mother (Carolina Politi), who is in the process of divorcing his father. The two boys have no wish to do anything but play video games all day, but unexpected encounters with Rita (Danny Perea), a slightly-older neighbor girl who wants to use their oven to bake a cake, and a pizza delivery man called Ulises (Enrique Arreola) prove catalysts for a more usual and more melancholy sort of loss of innocence. This is nothing spectacular, you understand — no death or deflowering of the dramatic sort to be expected in a Hollywood product. Rather, it is as understated as it is for most of us in real life, a dawning realization of things already half-known and somehow both sad and funny at the same time. I particularly liked the way in which Señor Eimbcke marked the division between childishness and gathering maturity by a power-failure and the reduction of the TV picture to that tiny dot of light that used to signal the end of transmission. He’s got that right too: in order to acquire real experience, we’ve got at some point to stop watching.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.