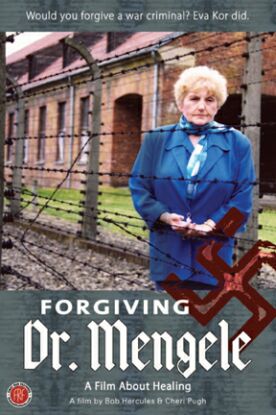

Forgiving Dr Mengele

When the history of our times comes to be written, a whole chapter — nay, a whole volume — will have to be devoted to the Holocaust. Not, that is, to the Holocaust itself so much as to what has been made of it in the decades since it happened. It would not be too much to say, I think, that we define ourselves in relation to the Holocaust. This is of course not surprising in those who survived it, or who lost family members, but for some time now there has been a tendency among those who have no connection to the Holocaust to appropriate it as a metaphor, an icon, almost a state religion for the spiritual orientation of those who are otherwise spiritually rootless.

On one level this must be flattering to the remaining survivors, for they naturally become the prophets and martyrs of this new religion. One such is Eva Mozes Kor, a real estate agent in Terre Haute, Indiana, who is the subject of a new film, Forgiving Dr. Mengele, by Bob Hercules and Cheri Pugh. Mrs Kor was a Romanian Jew who as a child was, with her sister Miriam, one of the subjects of the twins studies of the infamous Dr. Josef Mengele at Auschwitz. All the rest of her family was killed.

So I suppose you could say she owed her life to Dr Mengele.

After liberation by the Soviets, she and her sister emigrated to Israel. There, both married, Eva returning to Terre Haute with her new husband, who was also a Holocaust survivor, and Miriam staying on in Israel. Eva became, to all appearances, a normal American housewife of the 1960s. She raised two handsome children and eventually landed a job in spite of her still-thick accent. “I survived Auschwitz,” she says of her battle against prejudice. “Do you mean to tell me I cannot sell real estate?” But in 1984 her sister in Israel became very ill. As a result of Dr Mengele’s experiments, her kidneys had not developed normally. Eva donated one of her own, but her sister was not out of danger. The doctors told her that if she could discover what it was that Mengele had injected her with, they would stand a better chance of saving her.

This sent Eva off on a painful journey back to Germany to interview Dr. Hans Münch, the only one of Dr Mengele’s associates to have been acquitted of the charge of war crimes at Nuremberg. He was unable to help her, saying that Mengele was a dilettante and a bungler who didn’t keep proper records and never shared his research with anyone. But Eva took a shine to the old man, not least because he confessed to her that he, too, was haunted by his memories of Auschwitz. “The Nazis had nightmares about Auschwitz?” she said to herself incredulously. It marked a turning point in her life. She invited Münch to return with her to Auschwitz for the 40th anniversary of the liberation the following year. This he did, to the obvious discomfort of other former camp-inmates who had returned for the same occasion.

“It was not tactful of her,” says one of her fellow twin-survivors, Jona Laks, who is Eva’s nemesis throughout the film. But Eva has obviously never been one to care much about tact. Instead, she sent a letter of thanks to Dr Münch in which she also extended to him her personal forgiveness for the crimes committed against her. This made her feel so good that she said to herself, “Well, Eva, you’re forgiving Dr Münch. That’s very good. Will you forgive Dr Mengele?” And she did! Again, the feeling this produced was unexpectedly gratifying — because of the fact “that I had the power to forgive that little god of Auschwitz.” In other words, it made her no longer the victim but the superior of her now-dead tormenter and encouraged her to go on to forgive all the Nazis.

The rest of the film follows her as she goes about teaching and lecturing on the power of forgiveness like someone with a new patent remedy at a medicine show. The film is coy about whether or not she personally profits from her evangelizing, but it implies that any gain is funneled into Eva’s own storefront Holocaust museum in Terre Haute. More generally, the film-makers are themselves too tactful to look critically at the soupy vocabulary of “healing” and therapeutic self-help which is admittedly stiffened and given substance before audiences of young and yearningly empathetic Americans by her connection to the most personally authenticating event of the last century.

But it is not only Mrs Laks who expresses doubts about all this in the film. Its most memorable bit comes when Eva meets an Israeli peace activist, Dan Bar-On, at a conference in London, and he arranges for her to take her forgiveness tour to Israel and a meeting with a group of aggrieved Palestinians who, without quite saying so, regard her and other Israelis as the Nazis in their own national story. Suddenly, forgiveness doesn’t seem quite so empowering. Rather the reverse in fact. Somewhat — but only somewhat — ruefully, Eva confesses that “maybe forgiveness cannot happen for people when they are fighting for their lives.”

It is a serious fault in Forgiving Dr. Mengele, I think, that it does not make more of this moment as a qualification — to put it tactfully — of the inspiring life story it seeks to tell. But as an account of what must be one of the more memorable meetings between American religiosity and the entrepreneurial spirit it is still worth seeing.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.