Passion Without Reason

From The American SpectatorPublic suffering is the prerogative of the celebrity. In fact, you could almost say that public suffering is what makes him a celebrity. I use the word “him” in that sentence not only because I wish to uphold the English language’s long tradition of using the masculine as what grammarians call “the unmarked gender,” but also because, when it comes to public suffering, the male variety has much more resonance. The reason for this is the residual cultural expectation, left over from the old and now nearly extinct honor culture, that men but not women will be stoic and not show that they suffer. “Art thou a man?” Friar Lawrence rebukes Romeo as he lies “weeping and blubb’ring” at the news of his banishment from Verona and Juliet. “Thy form cries out thou art;/Thy tears are womanish.” To the extent that this expectation survives, there is still something slightly shocking about manly tears and cries of pain. Also something titillating and romantic. An exhibition this summer at the National Gallery in London called “Rebels and Martyrs” traced the history of the Romantic association between art and the emotions of the artist — a history that runs in parallel to the history of celebrity. As the exhibition catalogue points out, today’s celebrities are the heirs of the romantic rebels and artists of the Victorian era, when the fashion for such beings began. It doesn’t note that there is something of a falling off there.

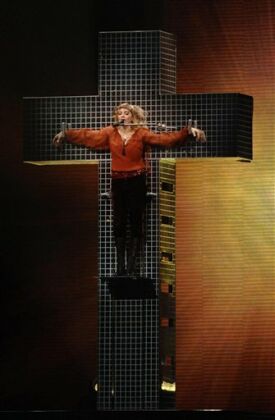

It was, perhaps, one thing when van Gogh or Gaugin portrayed the suffering Christ with his own features, but when Madonna, as part of her new “Confessions” tour and continuing the theme of fake divinity first announced with the adoption of her assumed name, puts on a crown of thorns and has herself hung on a mirrored, disco-ball cross while singing (or pretending to sing) “Live to Tell” in front of a montage of African AIDS orphans, we can’t help thinking that the martyrdom conceit must have just about played itself out. I wonder if even Madonna’s biggest fans can possibly regard the sight of her suffering for the sins of the world as anything but ludicrous? But then I reflect, yes they probably can. There is nothing like self-pity for insulating a person from reality. And besides, the religious significance of crucifixion and other forms of genuine martyrdom has itself become obscured by the fashionable wallow in public suffering. That, to me, was the meaning of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. No letters or e-mails please. I know I’m in a small minority of conservatives and American Spectator readers on this one. But I wonder if Mel’s many fans — whom I expect to continue being his fans in spite of his own recent martyrdom to drink and compulsive bigotry — weren’t made just a trifle uneasy when his interminable flagellation scene was reprised in this summer’s Superman Returns.

There’s always been something hilariously camp about the Man of Steel as he goes about leaping tall buildings in a single bound in his cape and fetching blue unitard with the red underpants on the outside. But once his invulnerability included an invulnerability to emotions as well as bullets. That, at any rate, is how I remember him being played in the 1950s TV series by George Reeves, whose steeliness was as much of the physiognomy as it was of the physique. Lois Lane might have been carrying a torch for him, but it was always pretty clear that he could take her or leave her alone. As we would expect of this interplanetary visitor, he didn’t have much of a human side himself but left all that kind of thing up to his alter ego, the not quite plausibly human Clark Kent. With the advent of the celebrity era, however, even Superman had to be humanized. There was now no longer any need for Clark Kent, though he was kept around, ever less plausible as a disguise for Superman, as a kind of running, self-referential gag. The god-like figure was now expected to condescend to the mortals he lived among and show that, like all celebrities, he was “just like us” — only more so. As played by Christopher Reeve back in the 1970s and by Brandon Routh in Bryan Singer’s new film, he became all about the emotions. His passion for Lois could make him reverse the rotation of the earth and, in his latest incarnation, he’s become the one who’s carrying the torch for her.

And that’s not to mention his passion and martyrdom at the hands of Lex Luthor (Kevin Spacey). At least Mr Singer’s film gives more space to the resurrection than Mr Gibson’s did. It’s not the only way his Christ-figure is more Christ-like. We also get to witness Superman’s all-encompassing compassion. Lois may think that she’s “moved on,” as she tells him, that “the world doesn’t need a savior, and neither do I.” But Superman knows different. He takes her up far above the city and asks her if she hears anything. She doesn’t. “I hear everything,” he tells her. “You wrote that the world doesn’t need a savior. But every day I hear people crying for one.” As it does with Madonna with her AIDS orphans, such ostentatious compassion is there to demonstrate the god-like figure’s entitlement to his place in the pantheon. His (or her) suffering is not merely private but undertaken on our behalf, and on that of all who suffer. The celebrity culture indulges itself in such myth-making because it needs to explain to itself, and to justify to itself, the world of the lesser deities of the silver screen that it has created to take the place, as I pointed out in our last issue, of the real saints and martyrs and heroes that have now been mostly debunked.

I mention the trouble I got into over The Passion of the Christ partly because I suspect I’m about to let myself in for more of the same by criticizing Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center — and for the same reason: namely, that it’s all passion and emotion with very little in the way of context. As everyone will know, the film tells the true story of two New York Port Authority policemen, John McLoughlin (Nicholas Cage) and Will Jimeno (Michael Peña) who were trapped in the rubble of the World Trade Center on September 11th, 2001 and eventually pulled out of it alive and reunited with their anxious and loving families. You might not think so, but it’s a natural cinematic subject for Oliver Stone. Sure he leaves out the left-wing politics and conspiracy theories — a fact for which I join my fellow conservatives in being profoundly grateful — but he’s always been a director with a strong appetite for strong emotion. And here he’s got it in plenty — not only in the suffering of the men themselves but in the extreme anxiety of their families about them. All of us who remember 9/11 will naturally share in that in our small way, which adds even further to the film’s undoubted emotional impact.

Yet the absence of the politics and the conspiracies also creates a void at the center of the film that Mr Stone doesn’t quite know how to fill. There’s only one moment when the emotion is put into any kind of political context (and it is a political context that it needs), which is when the one hero in the film who acts instead of suffering, Marine Sergeant Dave Karnes (Michael Shannon), says to the camera: “We’re going to need some good men out there to avenge this.” Out there! He doesn’t even say where “there” is! Are our boys in Afghanistan and Iraq — where the real-life Sergeant Karnes was later to serve two tours of duty — avenging it? Many of Mr Stone’s friends on the left think not; what does he think? And who does he think caused this suffering, and why? He pretends not to know for the sake of giving us the point of view of the poor sufferers at ground zero who didn’t know at the time what those of us with a bit of perspective on those sufferings learned about Islamic fanaticism in a day or two. Having Will Jimeno being pulled out of their ruins only to ask: “Hey! Where’d the buildings go?” is one of many reminders that the truth of lived experience often comes without context, just like Mr Stone’s movie. Approaching that experience in his way makes for a lot of effective if fatiguing cinema, but it is also a cop-out. For the celebrity film-maker must be like god in at least one way, by giving meaning to the suffering he shows us. Only thus can he prevent it from becoming nothing but the pornography of pain.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.