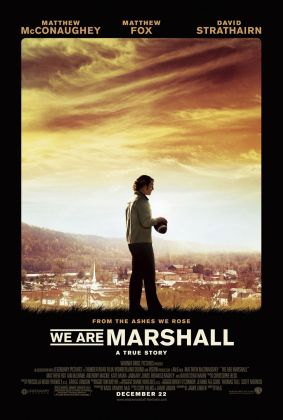

We Are Marshall

It may sound odd, but the thing that bothered me most about We Are Marshall is the name of the director. Billed only as McG, the gentleman shuns the name given him at birth by his parents, which was Joseph McGinty Nichol, McGinty being his mother’s maiden name. It’s the name of an honest worker who, glad to be known as a member of his own family, is likely to take pride in his workmanship as well. McG, by contrast, is the name of someone desperate to stake his claim to celebrity — and who, in doing so, sees himself and wants us to see him as sui generis, all on his own without forebears or descendants. He’s nothing but a great big shining star, all alone in the firmament and instantly recognizable (he hopes) by those three letters — one fewer even than Cher. Does this matter? I suppose not if this were Charlie’s Angels or Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, which are his previous feature credits, or the music videos he mainly did before that. But We Are Marshall is a movie about community, family, memory — the very things that his made-up name denies. How seriously, therefore, can we take what he has to say about them?

The question is particularly important because the story he is telling is a true one. On November 14th, 1970, while returning from a game against East Carolina, almost the entire football team of Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia, together with most of its coaching staff and a number of boosters and supporters, was killed in a plane crash. The rest of the season was of course cancelled, and it looked as if football at Marshall was finished, at least for some years to come. But a group of students led by Nate Ruffin (Anthony Mackie), a team co-captain who had been left behind on account of an injury, organized to demand that the university’s president, Donald Dedmon (David Strathairn), take steps to field a team the very next year.

According to the movie, anyway, on the other side was the supposedly “composite” character of Paul Griffen (Ian McShane), a local industrialist supposed to have been both a member of the university’s board of governors and father of the golden-boy quarterback who had been killed. “It wouldn’t be a game anymore, Don,” he says of the proposal to revive Marshall football. “It would be a weekly reminder of what we have lost.” Don, as you might have guessed, goes ahead anyway and engages Jack Lengyel (Matthew McConaughey) as his new head coach. Jack, in turn, persuades the one surviving coach of the old team, Red Dawson (Matthew Fox), to come back for one year to help out, though his own fortuitous escape from the disaster has so traumatized him that he is ready to give up football completely — and he does so after his year as Jack’s assistant.

Emotionally, you will see already where this is going. On the one side, you have the continuing grief of Red Dawson, Paul Griffen and others, always threatening to drag us down, and on the other you have the gentle and humorous proddings and cajolings of the determinedly amiable Jack Lengyel pointing us towards an uplifting conclusion. In this respect, We Are Marshall is like every other football movie which pits an underdog against opponents they supposedly have no chance of defeating, but it’s none the worse for that. In fact, it’s the least original parts of the movie which are the most engaging and exciting and genuinely uplifting things about it. As they say, the old stories are best.

But we also see in the film a point of intersection between two contradictory American cultural tendencies: the athletic culture of victory above all and the therapeutic culture which eschews competition in favor of nurturing and self-esteem. Mr McG seems hardly to have noticed that there’s a conflict there. If grief and pain can be healed, at least in some degree, by victory, where’s the problem? Here it is. It’s a question of relative values. In the too-brief snatch of film before the plane crash, we see the doomed head coach saying to his players after their narrow loss to East Carolina: “There’s only one thing people remember, and it ain’t how we played the game. Winning is the only thing.”

This has become almost a cliché of American sports, and here is a golden, unmissable opportunity for the film to do with it what films ought to do with clichés, namely to explode them. If ever there were an invitation to dramatic irony, here it is. And yet Mr McG scarcely bothers to point it up. We can hardly avoid seeing that, in the long term, victory and defeat are merely footnotes. The one thing people remember is the sense of love and community that binds them together and that is so tragically fractured by the accident. But the film isn’t really very interested in this. If pitting a team of underdog freshmen — allowed by special dispensation of the NCAA — and walk-ons against a series of much more experienced foes and hoping for victory is going through the motions, the regular mentions of grief that form the backdrop to that drama is going through the emotions.

The two come together in the big inspirational speech by Jack Lengyel to the new Marshall team before the climactic game. He begins by saying that, like “everyone in this business who’s worth a darn, “he, too, believes in the old coach’s credo that “winning is everything and nothing else matters.” But, he adds, the grief they all feel sort of puts this on hold. “Some day we’ll wake up and be like every other team and winning will be everything again.” I don’t know about you, but I find this confusing. Is winning everything or isn’t it? Mr McG’s own hunger for celebrity suggests that he, if not Jack Lengyel, would say that it is, if only he thought he could speak freely. This to me smacks of the crassness of a success ethos like that of Marshall alumnus Randy Moss, now with the Oakland Raiders, who once said that the plane crash “really wasn’t nothing big.” Marshall deserves better.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.