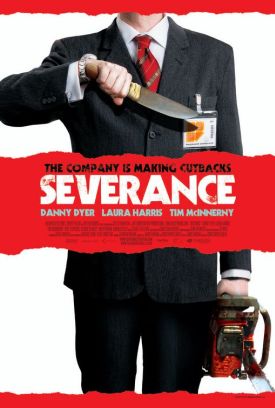

Severance

The hard part about making movies these days is all to do with special effects. They’ve made a whole second movie, a documentary called “Crashing a Coach,” especially for the DVD of Christopher Smith’s Severance to show how they filmed that movie’s coolest moment (as these things are defined nowadays) — in which we watch as a bus with people in it flips rather spectacularly and, well slides a long way on its side. I haven’t seen the documentary, but I’m quite prepared to believe that filming a bus crash is an immensely difficult and complicated exercise. I can testify that the end result is a visual treat for crash connoisseurs. Yet I can’t help wishing that a fraction of the thought and planning and energy that went into that effort had been spent on the movie’s plot.

But then that’s post-modern movie-making for you. Nobody cares about plot anymore. Well, nobody but me, apparently. And not only do movie-makers not have to care about plot, they rather enjoy teasing the audience about how they don’t have to care about it. Here’s the situation in Severance. Several employees of a British arms manufacturer called Palisade are on the bus to a rustic lodge somewhere in Hungary or the Balkans — there is also a tease about where they are — for a “team-building weekend.” Shadowy figures in the forest start bumping them off one by one. Who are the killers and why are they doing this? Not only does the film refuse to tell us, it glories in its own ignorance — or, to put it another way, in the motivelessness of its murders. It does this by providing three different explanations for the killings, each more preposterous than the last.

Harris (Toby Stephens) tells us that the lodge had been an insane asylum before the First World War. When the inmates had taken over, they had all been gassed with the help of Palisade-produced nerve gas. Or all but one. Since then the escapee (and, presumably, his heirs) has vowed vengeance against Palisade and all its employees. Jill (Claudie Blakley) claims that the lodge is the site where, after the break-up of the Soviet Union, Warsaw Pact soldiers who were a little too fond of killing had been sent. They too had been not-quite wiped out by their own governments using Palisade-supplied weapons. Steve (Danny Dyer) offers a third explanation. It is that the place had been an old-folks home where all the pretty young nurses had become frustrated into lesbianism by the lack of any virile young men — until someone looking a lot like Steve came along.

The joke of his offering an explanation that doesn’t even attempt to explain anything is an echo of the movie’s own jokey refusal to make sense in realistic terms. To Mr Smith, who directed and co-wrote the screenplay with James Moran, his film is all about the picturesque slashing and chopping and burning and stabbing and the black comedy he is able to wring from these various forms of violent death. The question of why any of it is happening doesn’t interest him. He thinks it shouldn’t interest us either, which is why he ridicules the very idea of plot and motivation. Well, fair enough, you might say. Except that the movie also has ambitions as a satire. You can tell by (among other things), its allusions to Cold War classics such as Dr Strangelove and the earliest Bond films. It’s as if it wants to tell us that the threat of superpower-communism may have given way to the threat from free-lance international terrorism but, really, nothing has changed. It’s all just a mad and dangerous world where nothing makes any sense.

The problem is that we know this is untrue. There is no mystery at all about the motivation of the terrorists who threaten us. Deliberately to close your eyes to this by treating the killer or killers in the woods as wild beasts who kill just for killing’s sake suggests that, like so many po mo products, this is really a movie about not the world we live in but other movies. The movie-take on war and armed struggle as nothing but senseless and irrational violence has been carefully cultivated for more than forty years — at least since the first Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns and Dr. Strangelove came out at almost the same time in 1963-64. The idea was a commonplace by the time that Francis Ford Coppola made Apocalypse Now in 1979, and it has remained so ever since.

If you find compelling the idea of yet another redaction of the same (false) idea — if admittedly one that has been spiced up with a couple of scantily-clad Serbian hotties brandishing automatic weapons, here and there some witty dialogue and other laughs plus a great bus crash — then you might like this movie. But I found it a crashing bore.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.