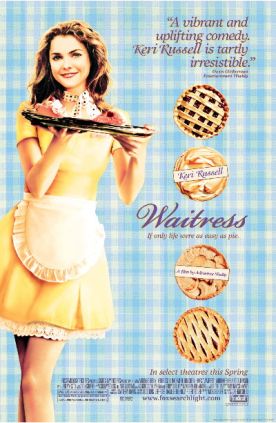

Waitress

Let’s stipulate at the outset that there probably are husbands as loathsome Earl (Jeremy Sisto) who are married to wives who are as sweet as Jenna (Keri Russell), the central characters in Adrienne Shelly’s “Waitress.” There may be even more loathsome husbands married to even sweeter wives — though Jenna is said to be “the queen of kindness and goodness.” But portraying such a lopsided relationship in a movie can have only one purpose, which is to manipulate the emotions of the audience. And those emotions can only be of the coarsest and can only number two: pity and moral indignation. For some, it’s true, there is a certain voyeuristic pleasure to be had from indulging themselves in — indeed, wallowing in — such feelings, and they will make up the film’s natural audience. But those who demand more sophisticated pleasures, even from so slight a confection as “Waitress,” are likely to lose patience with it pretty early on.

If they are from the South, the patronizing redneck stereotypes may make them lose patience very early on.

Miss Shelly, who was murdered in her Greenwich Village apartment last year while the film was in post-production, also stars as Dawn, one of Jenna’s fellow waitresses at Joe’s diner and pie shop in an unnamed Southern town. A third waitress, Becky (Cheryl Hines), makes up the trio whose man-troubles provide much of the material for the wise-cracking girlfriend-talk that is the second strand of material designed to make this a consummate chick-flick. The third strand is pie-making. Jenna is the acknowledged mistress of the pie-making arts — though Becky and Dawn agree that, miserable as their own lives are, they wouldn’t change places with Jenna, even if it meant being able to make pies that are as good as hers.

Jenna is also the unacknowledged mistress of her married doctor (Nathan Fillion), with whom she enjoys a sort of amour fou after finding out that she is pregnant just as she is finally on the point of leaving her “snake-husband,” Earl. Such a snake is Earl, in fact, that he won’t even let her go to the big pie-making contest at which her pies, said by the adulterous doctor to be “Biblically” good (whatever he can mean by that: I don’t remember any pies, good or bad, in the Bible), are sure to win the $25,000 grand prize. As Earl makes her turn her earnings over to him, he’s cutting off his nose to spite his face. But what can you expect from a man so jealous and controlling — not to mention loud, vulgar and violent — that he makes Jenna promise not to love the baby more than she loves him?

For much of the movie the contest is between not which of the two she loves more but which she hates more. The baby in utero seems to Jenna “an alien and a parasite,” and its advent has thwarted her plan for escape from Earl. But Jenna has to learn, as others do, how to cope with unhappiness, and she keeps us posted on her progress in Life 101 with regular voiceovers, ostensibly to the baby. Some of her life-lessons come from the girlfriends. Jenna sees her own behavior reflected when Becky, whose older husband suffers from dementia and incontinence, has a fling with Cal (Lew Temple) the manager of the diner. Jenna feels her own hypocrisy when she reproves her for the harm she is doing Cal’s wife. She also disapproves of Dawn’s finally accepting the proposal of Ogie (Eddie Jemison), whom at first she despised, on the grounds that she, Dawn, can’t really love him. “You shouldn’t be with someone only because no one else wants you,” she advises.

“Why not?” Dawn replies. “You are.”

The crucial lesson comes from Old Joe (Andy Griffith), who owns the diner as well as the town’s filling station and supermarket and whose curmudgeonly and cantankerous ways — “I love living vicariously through the pain and suffering of others,” he says — are not proof against the soft spot he has for Jenna. “It’s never too late to start over again,” he tells her. No prizes for guessing if she learns this lesson.

There are some funny lines in the movie, as when Jenna asks the doctor, while he is still just her doctor, how pregnant she is. “Very,” he replies. “There’s really only one degree of pregnancy.” I’m also inclined to credit it for the fact that part of the “message” that is otherwise so tedious is unmistakably — though, perhaps, in spite of itself — pro-life. Jenna considers selling her baby, but not aborting it. But these qualities are not enough to save “Waitress” from the crudeness of its caricatures and the sugariness of its sentimentality, which makes a cinematic pie that even a redneck wouldn’t describe as Biblical.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.