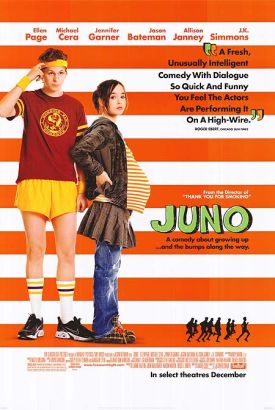

Juno

Graham Greene’s 17-year-old gangster, Pinky, the hero of Brighton Rock (1938), was said to know “everything in theory, nothing in practice.” He could have been the prototype for the age of cool that was to come along a generation later with the Beats and their successors in the 1960s. Pinky of course, had a good reason to want to keep his innocence well-hidden from the fellow gang members who looked to him for leadership, but the post-war reign of cool began when innocence became, in principle and simply as such, something to be ashamed of. Back in those days — which now themselves seem quite innocent — it was principally sex that kids wanted to be knowing about, but now sexual sophistication can be taken for granted even in quite young teenagers. That’s why, today, the efforts of the cool-culture to root out such forlorn remnants of innocence as may still survive in the caves and mountain hide-outs of our cultural sophistication have had to become more inventive.

That is the message of Juno, directed by Jason Reitman and written by Diablo Cody, the nom de strip of a former exotic dancer who brings a perfect celebrity résumé as well as a sharp wit to her first produced screenplay. Sixteen-year-old Juno MacGuff (Ellen Page) gets pregnant by her clueless high school boyfriend, Paulie Bleeker (Michael Cera), decides to have the child and give it up for adoption, herself picks the childless couple, Mark and Vanessa (Jason Bateman, Jennifer Garner), to whom she intends to offer it and thereafter finds herself “dealing with things way beyond my maturity level.”

That line will give you an idea of what has made this movie so successful. Juno’s disarming candor together with a complete lack of shame about her interesting condition is meant to reinforce our sense of her emotional as well as sexual precocity. At the same time she is also as endearingly vulnerable as any 16-year-old. Look at the way she greets a high school classmate whom she unexpectedly meets protesting outside the abortion clinic she visits before thinking better of taking such a course to “deal with” her pregnancy. Su Chin (Valerie Tian) is chanting: “All babies want to get born!”

“You should try Adderall,” Juno tells her after offering a friendly greeting and an inquiry after her health.

“No, thanks,” says Su Chin. “I’m off pills.”

“Wise move. I know this girl who had a huge crazy freakout because she took too many behavioral meds at once. She took off all her clothes and jumped into the fountain at Ridgedale Mall and she was like, ‘Blaaaaah! I’m a kraken from the sea!’”

“I heard that was you,” says Su Chin.

Juno pauses and considers: “Well, it was nice seeing you, Su Chin.”

It is Su Chin who supplies the information — that babies in the womb have fingernails — which proves decisive in preventing Juno from getting an abortion — a detail which serves as a reminder of the weird mix of adult knowledge and youthful capriciousness, standing in for absent innocence, that makes Juno believable. Having thus established her, she then contrasts her with Mark, to whom she intends to entrust the fatherhood of her child but who turns out to be much more immature than she is.

Like all strippers, I guess, Miss Cody’s gotta get a gimmick, and the gimmick of Juno is this inversion. In principle, it’s not a bad idea, but she appears not to recognize what a cliché Mark is. The grown man who chooses to remain a perpetual adolescent as a way of hiding from adult responsibilities is now so familiar a figure that the last hit comedy to feature an accidental pregnancy, Knocked Up, also had recourse to him. There, at least, Seth Rogen’s slacker pot-head had to grow up fast, which made the picture more satisfying as a bit of moralism but perhaps less realistic. For Mark in Juno is an altogether more sinister type: a prosperous and outwardly respectable suburban home-owner in his 30s who makes a good living composing commercial jingles but whose attachment to kid-culture is so unshakeable that he sees no reason even in prospective fatherhood why he should ever have to grow up.

Juno

, like its heroine, takes this male immaturity for granted — as part of the melancholy truth about the world and about men that feminine maturity, inevitably in advance of the masculine even where that exotic beast still exists, must simply come to terms with. The only example of a mature man in the picture is Juno’s father, “Mac” (J.K. Simmons), and even he pretty much has to acknowledge himself beaten by the culture of immaturity when he tells Juno that “the best thing you can do is find a person who loves you for exactly what you are. Good mood, bad mood, ugly, pretty, handsome, what have you, the right person will still think the sun shines out your ass. That’s the kind of person that’s worth sticking with.”

In other words, don’t bother trying to seek out maturity and discipline and good sense as the qualities you are looking for in a prospective mate and the father of your children, even when you are in a better position to have some. You’re not going to find them anyway, so you might as well follow your heart. There is a kind of sour feminism behind this outwardly upbeat conclusion which presumably comes of the hard-won wisdom about the impossibility of changing people that we might expect from someone who told The New York Times that “everything is prostitution.” Vanessa, too, becomes much more likable on her own, when she is no longer trying to play mom to Mark and baby him into accepting the responsibilities of adulthood.

But the film’s celebration of the tight little circle of independent women who have decided to let the men go off and play with their toys without expecting anything more out of them strikes me as a counsel of despair. It even cuts across Juno’s chief virtue and the reason for its kudos — including, now, an Oscar nomination as Best Picture — namely the witty dialogue which speaks of a deep acquaintance with youthful aspirations to hipness. A lot of the laughs are owing to the fact that this dialogue is put in the mouth of a credible teenager, whose “maturity level” is thus artificially pumped up. But that doesn’t stop it from being funny, or for the film’s dark but humane view of the world not to be entertaining.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.