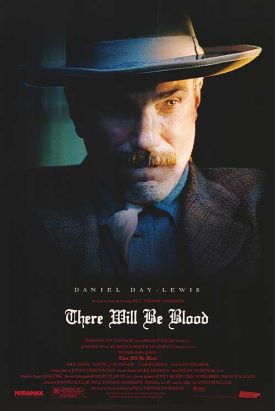

There Will Be Blood

Among the things I disliked about the very talented Paul Thomas Anderson’s movie There Will Be Blood, perhaps the thing I disliked most was its use of music. I could put up with a bit of Arvo Pärt to illustrate the otherworldliness of the Western landscapes through which the film’s hero, Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis), had to slime his way to make his fortune in the early days of the oil industry, and even the more constant and anachronistic static of Radiohead is not positively offensive. But the nobility of Brahms’s Violin Concerto as background music to a tale otherwise unredeemed by any but the slightest hints that there might be such a thing as human goodness or unselfishness was too much. It only served to underscore how pointless the movie was as anything but an opportunity for Mr Day-Lewis to play, as he so often does, the Great Actor and for Mr Anderson to play Orson Welles with this shot at a latter-day Citizen Kane, set in the heroic days of American “capitalism” — of which, of course, it is also a critique.

I’ve never been all that fond of Citizen Kane (1941) itself, to tell the truth, though cinéastes routinely vote it the greatest film of all time. Like There Will be Blood, it is obviously the work of a film-maker of corruscating genius, but the genius of the film-makers, great director and great actor, is the problem with their films. Both are too self-conscious and, ultimately, self-regarding. The artist is the hero of both (Welles doing both the directing and the acting in his), and in both he patronizes the life out of his principal character. Classical tragedy was supposed to inspire, according to Aristotle, pity and terror. These stabs at a kind of cinematic tragedy give us the pity without the terror, or with disgust in its place. No one looks at Charles Foster Kane or Daniel Plainview and sees himself the way we can see ourselves in Oedipus or Hamlet or Macbeth. Plainview, like Kane, is a would-be great man who has been set up only in order that his creator can tear him down — while leaving him, to be sure, a modicum of humanity with which to certify not his but his author’s spiritual largesse.

Plainview is an oil-man who, with a combination of trickery and ruthlessness, buys up all the prime oil leases around Bakersfield, California at a time (1911) when the area is inhabited by poor subsistence farmers. The farmers do not get rich off their land, but Plainview does. And he takes as much savage satisfaction from mastering them as he does from resisting the attempts of the big oil companies to buy him out. “I have a competition in me,” he says in a rare moment of self-revelation. “I want no one else to succeed. I hate most people. . .There are times when I look at people and I see nothing worth liking. I want to earn enough money that I can get away from everyone. . . I see the worst in people. I don’t need to look past seeing them to get all I need. I want to rule and never, ever explain myself.”

Of course he is explaining himself here, to a man he believes to be his long-lost half brother, Henry (Kevin J. O’Connor). “I’ve built my hatreds up over the years, little by little, Henry,” he goes on to confide: “to have you here gives me a second breath. I can’t keep doing this on my own with these — people.” But Henry, instead of relieving his misanthropy only confirms him in it. And, indeed, for all we see of these “people,” he seems to be more or less right about them. The words of Eli Wallach’s bandito, Calvera, in The Magnificent Seven come to mind. “If God didn’t want them sheared, he would not have made them sheep.” Eli Sunday (Paul Dano) is almost the only one among them who seems to know or care about what Plainview is doing to him, and he is a religious charlatan (which in Hollywood these days is a redundancy) who is happy to cooperate with him for his own purposes. At one point he stages a grotesque parody of Plainview’s conversion and repentance with no purpose but to exaggerate the wickedness of both men.

One person who seems to inspire feelings other than anger and contempt in Plainview is H.W. (Dillon Freasier), the orphan boy whom he adopts as his son in order the better to sell his drilling company to the rubes of rural California as a family-run operation. When H.W. gets too close to a gusher and is deafened by the explosion, we see Plainview running from the well with the child in his arms and anguish in his face — until he realizes that his presence is urgently required back at the well. What briefly looks like love turns out to be only sentimentality. Likewise, at one point he appears to prevent Eli’s little sister, Mary (Sydney McCallister), from being beaten for not praying (those darned Christians again!), but this is an isolated gesture and not followed up. By the end, neither Mary nor H.W. appears to mean anything to him.

The movie that Paul Thomas Anderson says he took as his model was not Citizen Kane but John Huston’s Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), which might get my vote as greatest movie of all time. It makes for a fascinating comparison, for what is missing from Blood is exactly what Treasure could have supplied, which is the powerful sense of ordinary human aspiration. Huston’s Fred C. Dobbs (Humphrey Bogart) was like Daniel Plainview in allowing the lust for wealth utterly to corrupt his soul, but his two companions, played by Tim Holt and Walter Huston, are our representatives on the spot: men who share Dobbs’s ambition but without his terrible, all-consuming monomania. The reversion at the end to a benign natural order from which the Dobbsian evil has been purged strikes me as not only more heartening but more true than the bleak war of each against all which is the world of There Will Be Blood.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.