Rock-Star Status

From The New CriterionNow, only a couple of months down the road, it’s a little hard to remember how, towards the end of last year, Hillary and Bill Clinton were being described as having “passed some point where they’re no longer just politicians. They’re rock stars.” I confess to having been among those who indulged myself in a certain amount of head-shaking and tongue-clucking about this description of them at the time (See “Clooney Tunes” in The New Criterion of December, 2007). Who was to know that it could all change so swiftly? I seem to feel the chill wind of mortality brushing the back of my neck as I reflect on the evanescence of something so seeming-solid — aren’t both rocks and stars by-words for permanence? — as “rock star” status. Or is it possible that, having been a metaphorical rock star, you can suddenly become something very much less exalted, and then hope to resume rock-star status again?.

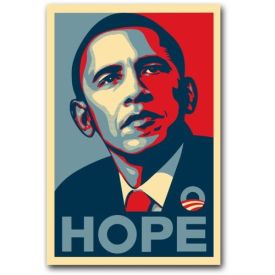

If so, the Clintons are likely to be the first to show us how it’s done, but at the time of writing there is no one in the media — and, very few out of it, I imagine — who would describe them as rock stars. Is this because Barack Obama has quite clearly become (once again I stress that this is at the time of writing) the Democratic rock star in the presidential race, and there is only room for one rock star at a time? Or is it all because of Bill Clinton’s crypto-racist slur against Mr Obama on the eve of the South Carolina primary which implied that the Illinois senator was only the latest version of that shake-down artist and two- (or was it three-?) time presidential loser, Jesse Jackson? Either way, slapping around a wide-eyed innocent like Mr O’Bambi, whose campaign is based on vague appeals to national unity and easy, non-partisan solutions of all the nation’s problems, looks like being the quickest way to lose one’s rock-star status.

The ways of the celebrity culture are not transparent enough for me to be able to say with any confidence whether the media grew disgusted with Bill (and Hillary) Clinton because they admired Senator Obama or whether they admired Senator Obama because they had grown disgusted with Bill (and Hillary) Clinton. The one thing does not preclude the other, I fancy. But so many voices so suddenly raised in anger against “the Clinton attack machine” — I had thought the Clintons themselves had taught us that “Republican” was the only possible adjective to describe that remarkable engine — suggests at the very least a certain amount of pent-up hostility in the media against the former rock stars from Arkansas. Perhaps, like the kings of Sir James Frazer’s Golden Bough, the old rock stars have to be ritually slaughtered before the new ones can be brought to birth.

If so, it was doubtless fitting that the knife should have been wielded by Ted Kennedy and Caroline Kennedy, the high priests and official keepers of the memory of America’s first rock star president — even if he was one only posthumously and retroactively. In late January, the two of them in concert, and in opposition to another wing of the Kennedy family who were supporting Mrs Clinton or remaining neutral, endorsed Senator Obama in particularly glowing terms. “I have never had a president who inspired me the way people tell me that my father inspired them,” wrote Ms Kennedy in an op ed article for The New York Times. “But for the first time, I believe I have found the man who could be that president — not just for me, but for a new generation of Americans.” That reference to the “new generation” was unmistakable code for “bring on the new rock star.”

Ms. Kennedy seems to have dropped her married name of Schlossberg even as Mrs Clinton has taken hers up with a new enthusiasm, asking for the full, old-fashioned M-R-S (once, we might remember with a certain amusement, an abbreviation of Mistress) instead of the trendy Miz and dropping the cumbersome “Rodham” altogether. It was another indication of the extent to which she recognized that her appeal was now mainly to blue collar and some-college Democrats while Mr Obama is the candidate of the Hollywood left and prosperous, highly-educated suburbanites for whom “inspiration” is more important than the kind of bread-and-butter issues that might be expected to concern the Missus. In the terms of New York Times columnist David Brooks, Mrs Clinton was Safeway, Mr Obama was Whole Foods. Or, as someone else put it — who had the idea first seems to be a matter of some controversy — Mrs Clinton was a P.C. while Mr Obama was a Mac.

Interesting, isn’t it, that so many people choose to express their confidence in the appeal of Senator Obama with reference to niche products whose market share is dwarfed by that of their bigger rivals? Yet it may well be that, in the world of celebrity politics, Whole Foods and Macs will swamp Safeway and P.C.s. There, as in the movies, the underdog always wins and the mad conspiracy theorist always proves to be right after all. Or maybe Mr Obama will only be able to prove his entitlement to celebrity status by an as-yet unimaginable act of self-immolation. Just look at the two celebrities most in the news in the early weeks of the Obama-Clinton primary battle, Heath Ledger and Britney Spears. The late Mr Ledger, who perished towards the end of January from an imprudent mix of tranquilizers, anti-depressants and pain-killers, underwent an instant apotheosis, while poor Miss Spears’s committal to a psychiatric institution provided the occasion for even more Schadenfreude than Mrs Clinton’s rock-star-ectomy.

To get the full public relations benefit of your self-destructive tendencies, it obviously helps if they haven’t been widely reported before you are found dead in bed one morning by your visiting masseuse. The element of surprise helps to bring out the elegiac in the media’s celebrity-watchers. As the staid, Daily Telegraph of London put it, “Ledger, like James Dean and River Phoenix before him, will stay forever young. His image on cinema screens will now always trigger a rush of might-have-been and could-have-done speculations.” This swiftly became the media’s familiar note about the 28-year-old Australian actor. Samantha Hunt of New York magazine wrote a dreamy, worshipful article about him and his former girlfriend, Michelle Williams, who had been New York neighbors of hers. It was headed: “Among Us,” as if the couple had been gods that had walked on earth.

“At the very least,” she wrote, “for a brief moment, we could stand next to the fire of their beauty, the breathlessness of their youth and glory, while we pretended to ignore them at Bar Tabac.” Jenny Lyn Bader of America’s newspaper of record also struck a classical note, comparing the star of Lords of Dogtown to Achilles. “When a 20- something superstar expires, one cannot help but wonder how many celebrities make Achilles’ bargain with fame. In a way it is comforting, perhaps even life affirming, for the majority of human beings, nonsuperstars, to think they have chosen the other course.” I wonder if Mr Ledger, popping pills in order to get to sleep in his lonely SoHo apartment, thought that he had made Achilles’s bargain with fame? I wonder if, like Miss Bader, he thought his fame was of the same kind that Achilles had bargained for, or if he took any satisfaction from his comforting, life-affirming negative example to us nonsuperstars? It seems unlikely, somehow.

Certainly Britney Spears has reason to think, if she thinks anything at all, of her own negative example, as it seems to be part of what makes the long-running story of her decline and probable fall so fascinating to people that she must have a claim to be considered, the greatest celebrity, qua celebrity, of all time. As Rosie Millard wrote in the London Sunday Times:

It is the anti-perfect-mother backlash which seems to be fuelling an obsession with the ups and more often downs of poor old Britney Spears. . . Knowing other mums aren’t perfect is comforting. We may sometimes lose our temper with our children. We may sometimes strap them into their buggies and leave them yelling in the middle of the sitting room. We may even throw something precious of theirs in the bin. Deliberately. But at least we have never behaved quite like poor old Britney, which is something to hold on to in the dark hours of the morning when that teeth-gritting demand of “Mummeeee! I need a peeeee” comes issuing from the little bedroom for the umpteenth time. While the Spears story has a core of grief and pain, it is an undeniable truth that reading about someone else screwing up makes your life look a bit better. It’s a nasty truth, but it is true.

Could it really be this which makes of Britney’s various personal dysfunctions a $120 million-a-year, one-woman industry? Can it be simply mommy-guilt which makes one of the two main paparazzi agencies in Los Angeles estimate that 30 per cent of its business is generated by Britney alone, or US Weekly to report that it has to increase its print run by 20 per cent whenever Britney is on the cover? A professor at UCLA estimates that she has been worth as much as a billion dollars to the American media over the last three years. And more, of course, to the international media. The British magazine OK! has ten people in Los Angeles who are dedicated full-time to Miss Spears. “We’re on constant Britney alert,” says its U.S. editor.

Surely, that can’t all be the result of harried mothers wanting to feel better about their own maternal malfeasances? The rest of us must have a similar interest in the egalitarian version of tragedy which the celebrity culture so often affords us. Paradoxically, classical tragedy, which dealt with the fall of a great man, invited the audience’s participation in that fall through its feelings of pity and terror, as Aristotle put it. Equally paradoxically, the egalitarian tragedy does the opposite: it encourages the audience’s sense of self-congratulation at its exclusion from the ranks of the god-like celebrities whose careers have otherwise been shaped by redundant demonstrations of the proposition that they are “just like us.” Perhaps we demand this of them because we are secretly persuaded that it cannot be true and that, like the gods and heroes of old whom they otherwise so closely resemble, celebrities really are a breed apart.

That might also explain why, the example of Barack Obama so far to the contrary notwithstanding, there is a noticeable if not exactly measurable popular resistance to the idea of politicians becoming celebrities. As I have already noticed, President Kennedy’s celebrity came only after he was safely dead. We have allowed a certain celebrity to the Clintons, but mainly since they left the White House. And Mrs Clinton’s electoral travails seem to suggest that we are not very happy about it. So, too, does the precipitous decline in the approval ratings of President Nicolas Sarkozy of France who, between the death of Mr Ledger and the release of Britney Spears from her second stay in a psychiatric hospital in a month, married a former model and aspiring pop singer named Carla Bruni after a two-and-a-half month courtship — so brief that the Clintons were still dazzling the media as rock stars when the couple first met in mid-November.

There is some evidence that President Sarkozy had his eye on rock-star status before that. After his election last May, he was quoted as having said of his then-wife: “You liked Jackie Kennedy? You’re going to love Cécilia Sarkozy!” Alas, the charming Cécilia left him soon afterwards — for the second and final time — thus creating a vacancy both at the Elysee Palace and in Nicolas’s bed. It was not too surprising, then, if he was in a bit of a hurry to find another candidate for the new Jackie Kennedy, and Miss Bruni, the former lover of Mick Jagger and Eric Clapton — and of the son-in-law of one of the world’s very few celebrity philosophers, Bernard-Henri Lévy — was an obvious candidate. But even Jackie Kennedy wasn’t yet Jackie Kennedy when she was Jackie Kennedy, if you see what I mean. As First Lady she was certainly more glamorous than any of her predecessors, but the celebrity-status she enjoyed (if “enjoyed” is the right word) in the years after her first husband’s death bore little resemblance to the way she was seen in the White House.

Then she was a part of the old honor-culture which was barely to outlive the Kennedy administration. After that, as the surviving Kennedys have repeatedly shown us — most recently in the Obama endorsement — there was nowhere to go with their fame but to the world of celebrity. Yet subsequent politicians, at least until the Clintons, have been unable to follow them there. In the movie The American President (1995), written by Aaron Sorkin and directed by Rob Reiner, Michael Douglas played President Andrew Shepherd, a widower who fell in love with a left-wing environmental lobbyist, played by Annette Bening. A lot of Mr Sorkin’s later fantasizing about an ideal liberal Democratic president in “The West Wing” was prefigured in this film, but in retrospect what is most interesting about it is that it was conceived almost entirely in non-celebrity terms. No Sarkozy-Bruni liaison this! President Shepherd is a somewhat squishy liberal who has his backbone stiffened and his progressive instincts reinforced by his lady-love, who takes him in hand and leads him to the classic Hollywood ending in which he loudly proclaims his attachment to all kinds of causes that no imaginable real-life president would be caught dead advocating.

At least not unless he was the kind of celebrity that President Shepherd is pointedly not. Even Aaron Sorkin didn’t want that. Yet it seems to me undeniable that the value of celebrity status in politics — as Al Gore has learned since his defeat in 2000 — is that it allows you to moralize about things that are properly only political differences. Celebrities who make moral crusades out of global warming or third-world poverty or opposition to the war in Iraq are only doing what comes naturally to celebrity, which is modeling the latest fashions. And in the process they are confirming their own celebrity status, which is what makes us more indulgent to the stars than we are to actual politicians. But that doesn’t mean that we want the stars themselves to be politicians. Fred Thompson might have thought of this before embarking on his ill-judged presidential campaign.

Hollywood fantasy apart, we have never elected a celebrity president. Heroes, yes; celebrities as we know them today, no. Bill Clinton became a celebrity, at the earliest, only in his second term, as a result of l’affaire Lewinsky and after he had won his last election. Though polls suggested that he might have won a third term, had he been eligible to run for one, I wonder if part of the reason for this was that everyone knew he wasn’t eligible. Similarly, Al Gore is now immensely popular, I think, because he has chosen celebrity politics rather than the practical kind. The whole global-warming business, which he describes in his Oscar®-winning documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, as a moral rather than a political matter, is tailor-made for celebrity politics, as last summer’s Gore-produced, “Live Earth” extravaganza showed.

In celebrity politics, decency and humanity cry out against some massively unfeeling and inhuman predator — war, poverty, AIDS, climate change — which those less sensitive and caring than the celebrities and those who admire their fine souls are insufficiently alarmed, if not actually criminally negligent, about. Yet Mr Gore must at least have an inkling, denied his former boss, that translating his pop-cultural popularity from this kind of moral posturing back into electoral terms is at best a very iffy business. Bill and Hillary Clinton may have three Grammy awards between them, but once they plunged back into the electoral whirl, their celebrity cachet washed away with remarkable swiftness. Even an Oscar, even a Nobel Peace Prize, might not be proof against the same forces.

Interestingly, it was Mr Obama who won this year’s Grammy for spoken word recordings — the day after he took four more states from former rock star Hillary Clinton. This makes him a two-time Grammy-winner as well. Let’s hope it doesn’t jinx him. But if I were in his place, I would be a little bit wary of assuming the rock-star status that the media have been so eager to thrust upon him. Just look at what happened to the last Democratic candidate so anointed. For, like rock’n’roll itself, the rock star is inevitably the voice of what the late Russian critic and theorist, Mikhail Bakhtin called the unofficial culture, which was the Dionysian underworld of bawdry and self-indulgence and untrammeled appetite that used to seethe beneath the Apollonian surfaces of disciplined, self-denying officialdom.

For more than a generation now, the official culture has been in headlong retreat from the newly resurgent unofficial culture, as the latter has gushed forth from its formerly dank and disreputable confines to join and, indeed, to overwhelm the mainstream. The presidency is still — or has been up until recently — one remaining piece of the old order that people have wanted to retain. Republicans who impeached President Clinton in 1998 may have thought that this impulse was stronger than it proved to be, but the former president’s survival on that occasion may have had more to do with popular resentment against the Republicans for making the presidential sexual proclivities public than with a laissez-faire attitude towards those proclivities themselves.

All this is by way of speculation, of course. America may well be ready to elect its first rock star president. All the psephological signs seem to be pointing that way — as does Senator Obama’s apparent successes, at the time of writing, by hitting with his campaign rhetoric almost exclusively the vaguely well-intentioned notes characteristic of celebrity politics. Should he triumph in November over a genuine official-culture sort of hero like John McCain, as polls now indicate he may well do, it will mark a definitive turning away from the last remaining vestiges of the old honor-culture and the adoption of rock star, celebrity politics as a permanent feature of our public life. Or at least one which lasts as long as it takes us to realize that celebrity-style caring about the world’s most intractable problems is not enough to solve them.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.