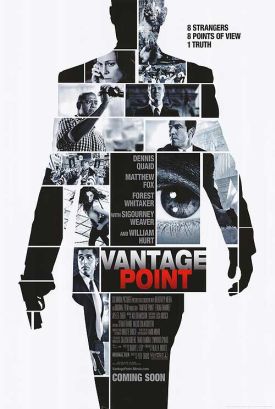

Vantage Point

There are a great many silly things about the movie Vantage Point, but none sillier than its apology for the most lethally effective of its terrorists. This is a man named Javier (Edgar Ramirez) whose superhero-like abilities single-handedly to kill scores of American Secret Service agents as he cuts a path to the unexpectedly vulnerable president of the United States (William Hurt) during a high profile appearance in Salamanca, Spain, are supposed to be the result of his training by Spanish (sic) special forces. Javier, you understand, is not himself a terrorist. But the two people we meet who are (Said Taghmaoui and Ayelet Zurer) are holding his brother hostage and threatening to kill him unless Javier obliges them by killing all those Secret Service agents — and anyone else who gets in his way — and then kidnaping the president.

Uh, OK, says Javier.

Please. The lengths to which this movie will go not to identify its bad guys with any real-world bad guys, or with any cause — say that of Islamic jihadists, to pick one at random — that motivates acts of terrorism in the real world must be an exercise in politically correct multiculturalism. Though they might or might not be Islamicists, the two terrorists never reveal any political leanings of any kind, nor do we find out what they have planned to do with the president when they have kidnaped him. Perhaps they’re only doing it for the fun of it — or, I suppose because there wouldn’t be any movie otherwise. But this means that the movie, directed by Pete Travis from a screenplay by Barry Levy, is completely unashamed about saying that it is meant to be nothing but fantasy, unconnected to real life in any way.

As if to emphasize the fact further, it is constructed around a very movieish gimmick. Supposedly, it tells us the same series of events from several points of view in sequence. Each time the clock is set back to the beginning as in Groundhog Day, and we have the same things happening but with a little more of the picture filled in. This happens six times, and every time it gets a little more annoying. For the multiple perspectives do not add anything to the story-telling, nor do they amount to genuinely different points of view. Rashomon this very emphatically isn’t. It’s just the director’s little tease, a device that has no discernible purpose except to make his film look a bit more arty.

Also adding a fashionable touch is the damaged hero, a Secret Service agent named Thomas Barnes (Dennis Quaid). Barnes is supposed to have leapt in front of a would-be assassin some months earlier and “taken a bullet” for the prez. Now recovered from his wound, he keeps having flashbacks to the awful moment and is on some kind of prescription drug, perhaps to help him forget. Has he come back to work too soon? Has he got the shakes as a result of his experience? Above all, is he now going to choke when a new threat presents itself? Can you stand the suspense?

In other words, this venture into cinematic geopolitics turns out to be all about the agent’s personal case of PTSD. Or maybe the family troubles of the American tourist (Forest Whitaker) who catches an apparent assassination attempt on his video camera. Or maybe the filial attachment between Javier and his brother or the ambiguous relationship between the female terrorist and a Spanish policeman (Eduardo Noriega). I don’t think it can be about Sigourney Weaver’s network news producer, but you’ve got to wonder what she’s doing there. But it might be about anything except the big public and historical event — an act of terrorism that cannot but have world-shaking significance — that brings all these people together. That’s just this movie’s McGuffin.

This catastrophically bad bit of writing is what creates an unintentional laugh-out-loud moment at the climax of the film when we learn who it is on the inside of the president’s security detail who is cooperating with the terrorists and, having assisted them in killing hundreds of people and throwing both the city of Salamanca and the international order into chaos, this person is confronted by our hero. “You used me!” says Agent Barnes.

Yeah, and that’s not all he did, bub. Not that you could be expected to care about any of that other stuff. As if to make up for turning the political into the personal, Vantage Point also offers us a few throwaway lines, not obviously relevant to anything in the plot, just in order to establish its Hollywood bona fides. Mr Hurt’s President Ashton is, like Martin Sheen’s President Bartlet on “The West Wing,” a bit of liberal wish-fulfilment, so of course he puts the kibosh on the insistence by his more gung ho aide, Phil McCullough (Bruce McGill), that he respond to terrorism by bombing a terrorist camp in Morocco.

“We have to act strong.” whines McCullough.

“No, we have to be strong,” replies the president. Or, failing that, at least not act strong. Anything but strike back or do anything else that might involve going to war. This makes it particularly odd that the nearest we get to a motivation for the traitor is his claim that “This war will never end.” What war? There is no war in this movie, and the president explicitly disavows any attempt to wage one. Nothing makes any sense. But at least — spoiler alert! — Agent Barnes gets his nerve back and we get to watch, once the gimmick is forgotten, a sequence of non-stop, fast-paced action, including a car chase. Be honest. That’s all you wanted anyway.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.