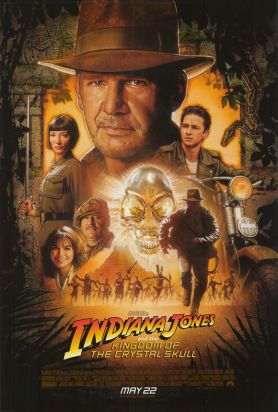

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull

The best line in Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (written by David Koepp from a story by George Lucas) comes right at the beginning when the title character, still played by a game but now-aged Harrison Ford, is single-handedly battling a gang of Russians who have invaded and taken over an American military base. The improbably sexy leader of the commies, Agent Irina Spalko (Cate Blanchett) taunts the hero, whom she has briefly in her power, by saying in the tones of the comic-book villainess she is: “No defiant last words, Dr. Jones?”

Indy outwits his captors as he always does, but before he springs away like the sprightly 40-year-old he was a quarter of a century-ago, he cries out: “I like Ike.”

Like most of the other lines in the movie, it is intended as an in-joke. There is no question of Indy’s really liking Ike — which, for younger readers, was the nickname of America’s 34th president, Dwight Eisenhower. It’s meant as a nudge and a wink to the audience, a reminder that here we’re only playing at being two-fisted, 1950s-style action heroes. We’re not to suppose that this Ike-liking paragon is something anyone could take seriously today — or even at the time, for that matter. It’s just the movie’s way of claiming for its hero a moderate, even apolitical liberalism meant to contrast with the supposed zealotry of the communists. The line is the post-modern equivalent of Bill Buckley’s reply to the John Birch Society’s accusation that Eisenhower was a communist: he was not a communist but a golfer.

More importantly, the picture can’t help being nostalgic for what it regards as an era of simple moral certainties, even though it shares none of these certainties itself. Into that ironic gap, as into a po-mo black hole, this movie quickly and completely disappears. It’s also why the plot is even more absurd than that of the original film, involving as it does space aliens in place of the more traditional supernaturalism of the Ark of the Covenant. I guess when you consider that the 1982 Ark ultimately turned itself into a lightning machine for zapping Nazis with some kind of melt-ray, it’s not so different. The space aliens might have been involved there too, since we now know that they were must have been playing around with similar technologies in ancient times.

Anyway, biblical mysteries have presumably lost some of their allure during the intervening decades, perhaps on account of The Da Vinci Code, and space aliens are always a convenient way to short-circuit any questions about advanced or, indeed, impossible technologies as well as to explain the persistence of such legends as El Dorado. You’ll not be surprised, by the way, to hear that Indy, having already bagged the Ark of the Covenant, some world-mastering sacred Indian stones and the Holy Grail, now adds another notch to his bull-whip and bests all those old-timey conquistadores by finding the city of gold — as well as the fact that those cool aliens were archaeologists like himself, and collectors of human artefacts.

But the real point of the movie is to re-unite Indy with Karen Allen from the original Raiders of the Lost Ark and — spoiler alert! — through her to provide him with a long-lost illegitimate son and heir called Mutt (Shia LaBeouf). Mutt embodies all that Hollywood remembers about the 1950s besides “McCarthyism,” which is the leather-jacketed, rebel-without-a-cause type teenage desperado and first avatar of the youth culture. For this reason, Mutt rides a motorcycle like Marlon Brando’s in The Wild One and is always combing his D.A. hairdo like Edd, “Kookie,” Byrnes on “77 Sunset Strip.” That’s how we are meant to know what he stands for: the birth of the cool.

McCarthyism, too, gets a mention, by the way. For in spite of liking Ike, Indy gets blacklisted and persecuted by FBI agents who conform to the movie stereotypes of today — being vicious and stupid — rather than those of the period for FBI agents. His nervous university dean (Jim Broadbent) tells him that he himself will have to resign as he can’t be embroiled in “that kind of controversy in this charged climate.” He tells Indy that “I hardly recognize this country anymore. The Government has got us seeing communists in our soup” — which you might think an odd sort of complaint to make of the government in a movie that begins by showing a gang of non-imaginary reds taking over an American military base on American soil. Disgusted, Indy says he might go off to Leipzig to teach. Presumably it has slipped his mind that that would have made the government’s case for his being a subversive, since Leipzig was in communist East Germany at the time.

Anyway, he doesn’t go to Leipzig but battles the the communists simply as the bad guys du jour who, apart from a mention or two of Stalin, now deceased, don’t have any real existence as such but are only the usual cannon fodder to Indy’s one-man army. All that matters is that the latter has sired Mutt out of Marion, and Mutt will obviously continue the line on behalf of generations of coolness yet unborn. It’s sort of like a royal pedigree. His is the house of Attitude, which is the royalty of cartoon-land, though why anyone with a mental age greater than eleven would want to spend any time there is more than I can fathom.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.