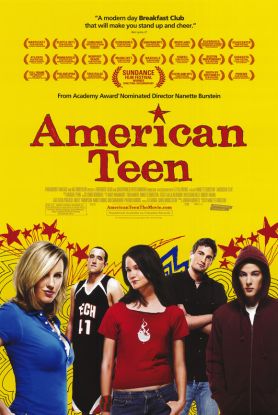

American Teen

American Teen is a bit of a con job, as pretty much all documentaries these days are, since it clings to the illusion that its cameras are the equivalent of a fly on the wall when we know this cannot be the case. It never could, really, though a generation or so ago people might have been able to be more genuine on camera than they can in our media-savvy age. That may be why a documentary about a quartet of real high school seniors from Warsaw, Indiana, recommended itself to the director, Nanette Burstein. But if she was thinking that her youthful subjects were more likely than adults to project ingenuous authenticity, I can’t imagine that she is overly pleased with the result — in spite of The New York Times’s reviewer’s marveling at “how unguarded these young people seem to be about their own lives.”

Yet — such is the magic of the movies — even though we know that what we are seeing is to some extent put on for the camera, we can’t help being caught up in it — which, I think, is really what people mean when they praise the movie for looking real. I, for instance, fell in love with Hannah Bailey, the one who is the daughter of the manic-depressive (and absent) mother and who shows worrying signs of going the same way herself. Too bad she’s the arty, rebellious type who wants to be a film student. The other subjects are recognizable high school types too: the popular blonde cheerleader, Megan Krizmanich, the jock and basketball hero, Colin Clemens, and the nerdy, reclusive member of the band and martyr to acne, Jake Tusing. Funny how it works out that way.

The most curious thing about the film is its underlying assumption, namely that we have something of sociological or even, perhaps, moral and spiritual importance to learn from the sort of adolescent angst that all of us have been through ourselves and so have already learned not to treat as the matter of world-shaking importance it seemed to us when we were kids. It’s as if Miss Burstein were herself taking this adolescent view of the world — and expecting her audience to do likewise — as she chronicles the traumas of puppy love and high school or small town status-seeking with the same seriousness as but with less excuse for it than the kids themselves have.

All of these youths are college aspirants, and the central dramas of the film in three of the four cases have to do with university entry in one way or another. There are months of suspense as to whether Megan will get into Notre Dame as all the rest of her family save one have done before her. The fact that the one who didn’t subsequently committed suicide adds a certain piquancy to her plight, I suppose. We are similarly left up in the air about Colin’s prospects of a basketball scholarship after he suffers from a serious shooting slump in mid-season. Without the scholarship, he won’t be able to go to college at all, which I’m sure is a worry for him — though it might have been more interesting for us to be given access to the inner life of some classmate who knew all along that he wasn’t going to college. Hannah wants to go away to the big city to college, against the wishes of her family.

Only Jake the Nerd seems relatively unfussed about the college career he seems to be able to take for granted. His big concern is with getting a girlfriend, which he does, briefly, by pouncing on a freshman and a new girl in town for the brief time it takes her to realize that she can do better than Jake. But the really big romantic drama comes when Mitch Reinhold, another basketball jock and better looking than Colin, goes sweet on Hannah, much to her bewilderment. “There are so many girls who would give their left boob to be with him,” she confides to Miss Burstein’s lens. “Did the axis of the earth just tilt?” But MItch soon sees that she doesn’t quite fit in with the others in the popular crowd and he dumps her by text message. That’s all he’s there for: to be a brute and a boor and to crush, on behalf of the high school élite, this delicate flower of a sensitive misfit.

Another of the film’s dramas comes when Megan blots her copybook and jeopardizes her shot at Notre Dame by vandalizing the house of the student council officer whose idea for the prom theme — “Welcome to the Jungle” — beats out her own, more elegant choice. “I know it’s wrong, but I just believe in getting even,” she says to the camera. Called on the carpet for it, she is told by the principal that she should be ashamed. “I am,” she says — but then she adds to the camera: “I have forgiven myself. I’m a quick forgiver.”

Her father says: “That was stupid.” But then he adds: “It was more stupid if you couldn’t do it and not get caught.”

When she is suspended from her student council office, she tells us that she thinks it “really unfair that I am being punished so much.”

Meanwhile, Jake is making the avatar of his more successful rival in love into his video game villain, so that he can “bring death and destruction to my arch-nemesis.”

Is any of this sounding at all familiar?

Like soap opera or really juicy gossip, these intertwined stories have the power at once to engage and amuse us, and to make us feel at least a bit embarrassed about our own eager interest in them. They are as highly wrought as soap opera too, even though they recommend themselves to us by being wrenched from “real life.” What the larger purpose of their telling might be, however, I cannot tell. The epilogue, which revisits the kids a year later, after their freshman year of college, may be intended to give the saga some meaning but, apart from a certain satisfaction in Mitch’s avowal that he would never again break up with a girl by text message — and he could hardly offer us less than that to atone for his appalling faux pas — I didn’t get the moral of the story either.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.