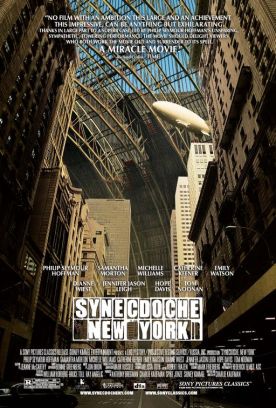

Synecdoche, New York

Like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), for which he wrote the screenplay, Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York, is a play about time and memory, and in particular the ways in which time both wounds and heals and memory becomes almost infinitely corruptible. Also like the earlier film, it makes use of the realistic bias of the medium to produce a quasi-surrealistic parable which has the power, like the best examples of surrealism, itself to become a kind of artificial dream or memory in the mind of the audience. At the narrative level, it is an essay about the particularities of life. How important are they, after all? A man’s wife leaves him, but there seems to be no shortage of willing females to take her place — though the man is severely depressed and, by most reckonings, not very attractive even apart from the fact that he suffers from various disgusting illnesses. One of them gives him another daughter. If you love, does it really matter that much precisely who you love? How about if you are loved?

“Synecdoche” is the rhetorical device of substituting the part for the whole (“hands” for workers) or, loosely and by extension, the whole for the part or other forms of metonymic substitution. It is also, in this context, a pun on name of the city in upstate New York, Schenectady, where the hero, Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is living with his wife, Adele (Catherine Keener) and their daughter Olive (Sadie Goldstein) when the film opens. Caden is a professor of theatre whose own production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman is about to open. The big idea of the production is to cast young actors in the roles of Willie and Linda Loman, so that the failure and futility that characterizes their aged selves will be seen as implicit in their young and (therefore) hopeful selves. In other words, time itself is to be filleted out of the play like the skeleton of a fish in order to reveal — well, what? A timeless life.

Instead of Synecdoche, maybe the film should have been called Tautology. Or, better still, Oxymoron. One of its central images is the house on fire that is never consumed. Hazel (Samantha Morton), one of women who are powerfully if inexplicably attracted to Caden, buys the house — she’s told it has a motivated seller — and lives in it for years, apparently, ultimately growing old there and dying (“Might be smoke inhalation,” says the paramedic) all the time that it remains, like the burning bush in the Bible, a paradoxical negation of time and the normal laws of the universe. But it is also a negation of what we normally take to be — the wise might say wrongly — the central fact of human life, which is that it is just one damned thing after another. No! says the Cadenesque and Kaufmanesque view. It’s the same damned thing over and over again, an endless rehearsal for a play which is never presented.

For that is what Caden’s life becomes in the telling of Mr Kaufman, who both wrote and directed the picture. Once Adele leaves him, taking Olive with her, to go to Berlin and become a famous painter, Caden wins a MacArthur “genius” grant, and with the money decides to produce a play on such a massive scale that it will become indistinguishable from life itself — in particular, his life. The point then becomes both to confuse the multiple Cadens, the star of the play as well as its author and producer, as well as to jumble up the times of his life, so that it is soon hard to tell whether it has been weeks or decades since Adele has left and the play has begun. At some point he marries Claire (Michelle Williams), the star of Salesman and has a daughter with her, so that she becomes a second Adele and the daughter a second Olive. He also hires an actor named Sammy (Tom Noonan) who has been following him around, he says, for 20 years to play himself. Sammy knows Caden better than Caden does.

Meanwhile, the original Olive becomes an exotic, tattooed dancer who dies when her tattoos become infected. On her deathbed, where Caden visits her, she tells him that she has to hear him ask for forgiveness for leaving her before she dies. He tries to persuade her of the account of events that we have seen — in which Adele left him and took her away to Berlin when she was a little girl. But Olive rejects this and vigorously opposes it with the rival narrative of Maria (Jennifer Jason Leigh), Adele’s friend and her own substitute father, as she tells it, which she obliges him to mouth word for word: “Can you ever forgive me for abandoning you to have anal sex with my homosexual lover, Erik?” he says obediently, though there is no Erik and he is not a homosexual.

Whereupon, she says, no, she can’t forgive him, and promptly dies.

How far either she or Caden are simply making up the story of their own lives we never know, though it soon comes to seem a matter of little moment. More important is the fact that Olive and everybody else are in some sense as much the directors and impresarios of their lives as Caden is of his. This is the reflection that gives rise to the film’s moral, which is that “there are nearly thirteen billion people in the world” — actually, it’s only about half that — ” and none of those people is an extra. They’re all the leads of their own stories. They have to be given their due.” To me this sounds like a counsel of despair, as does its corollary that the simulacrum is not reliably to be distinguished from the original.

In what might have been an affecting scene near the end, for example, Caden and Hazel in age embrace like an old married couple. “I wish we had had this when we were young,” says Hazel wistfully. “And all the years in between.” But in the context of the film, such a wish hardly makes any more sense than Caden’s wish for Adele to come back. They’ve had the life they have had — insofar as they, or we, even know what those lives have been — because of choices they have made. Regrets make no sense. But if there is nothing to regret, how can there be anything to love? The film seems to end by adopting Adele’s view that “This whole romantic love thing, it’s just a projection anyway.” If that were true, who would ever go to the movies? In the same way, if life were just an elaborate stage extravaganza, who would ever go to the theatre? This is a movie to kill the thing its author loves.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.