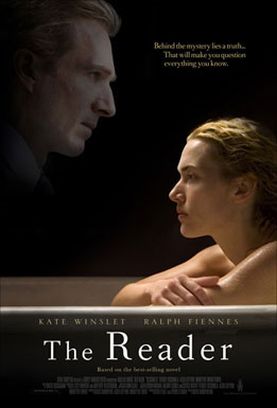

Reader, The

There are four or five human objects competing for our pity in Stephen Daldry’s The Reader, which was adapted by David Hare from a German novel by Bernhard Schlink — and if that’s not enough for you, there are six million more lurking in the background whose demands upon our sorely taxed sympathies might have been expected to feature just a bit more prominently. Instead we have two principal incitements to compassion. One is a beautiful, sensitive and even intelligent woman who happens to be illiterate, is deeply ashamed of the fact and who shyly seeks out people to satisfy a rather improbable hunger for highbrow literature — wouldn’t romance novels be more her speed in real life? — by reading aloud to her. The other is a former concentration camp guard too stupid, or at least morally obtuse, to do otherwise than obey orders but who nevertheless learns to suffer terrible, soul-destroying remorse, years later, for having done so.

That these two pitiable figures are combined in the same woman, Hannah Schmitz (Kate Winslet), introduces an incoherence and sense of moral dislocation that would be fatal to the film even if it were not parasitic for its emotional juice on the Holocaust. In other words, poor Hannah is suspiciously overqualified for our pity, both because she needs that extra bit of emotional oomph to escape the gravitational pull of the Jewish victims that weigh her down and because pity is all that the film has to offer us — pity not just for Hannah but for her damaged teenage lover, Michael (David Kross), his depressed and emotionally unavailable adult self (Ralph Fiennes), and for the mother and daughter who alone survive her salient act of devotion to duty as a concentration camp guard. The two Michaels are also pitiable because they have, or have had, a remote, emotionally unavailable and probably tyrannical father.

As I may have had occasion to mention before, pity is emotionally and artistically inert. The only artistic — really, quasi-artistic — experience it can give us is one of feeling rather pleased with ourselves for having the correct, compassionate feelings about those whose lives do not touch ours at any point, apart from being the objects of our compassion. That’s why Aristotle combined pity and terror as the emotions he believed to be evoked by tragedy. The terror gave the pity something to combine with which made it artistically productive: terror that we might find ourselves in the tragic hero’s predicament and therefore could not stand aloof from it, as pity would otherwise allow us to do.

There is one moment in The Reader where Messrs Daldry and Hare try to evoke something like this sense of connection between their audience and the central event in their heroine’s life. It occurs during a courtroom scene in which the judge (Burghart Klaussner) looks down, judgmentally, upon Hannah as defendant, attempting to make her feel ashamed of the atrocity for which she is on trial, and she replies, simply, “What would you have done?” But though the judge is supposed to be nonplused by her question, it is a false one. What he would have done is to have unlocked the doors of the church in which she had allowed 300 Jewish women to burn to death in an air-raid. It is what any of us enlightened, post-war liberals would have done. Or think we would have done.

But the whole point about Hannah is that she is not an enlightened, post-war liberal. She is a bit of human flotsam from the Nazi shipwreck whose utter remoteness from us — made even more unbridgeable by her illiteracy — insulates her from any feelings except those of pity. Or possibly anger, which is given voice to by one of Michael’s fellow law-students at the suggestion that the poor guards didn’t really know what they were doing, or what the fate of their prisoners would be. “Everyone knew. The question is, how could you let this happen? Why did you not kill yourself when you found out?” And then he adds, “Put the gun in my hand, and I will shoot her myself. Shoot them all.” A little over the top, maybe, but at least it gives us a brief and somewhat bracing vacation from the pity party.

Either because Hannah’s pathos is so overdetermined or for some other reason, I find that which Mr Fiennes attempts to evoke on behalf of her former lover particularly irksome. He is introduced to us in the film’s first scene, set in 1995 — most of the story is told in a series of flashbacks to 1958, 1966, 1976, 1980 and 1988 (not, however, 1945) — making breakfast for and bidding farewell to a casual lover whose inability to penetrate his emotional reserve is intended as an explanation, I guess, of his seemingly constant state of unhappiness. He also has a daughter (Hannah Herzsprung) to whom he apologizes for unspecified neglect. His secret sorrow may have something to do with his premature loss of innocence to Hannah, or his silence during her trial, but either way, set against the emotional maelstrom of the rest of the movie, it looks pretty, well, pathetic.

Also, when he asks to visit Hannah in prison in order to persuade her to reveal her secret and so incur a lesser sentence than life imprisonment, he chickens out at the last minute. Is this meant to be seen as an act of moral cowardice echoing her own? Or has he simply decided to respect her decision to keep her illiteracy a secret even at the cost of the heavier sentence? It hardly matters. Once again, the sense of psychological damage to him in such a context seems annoyingly irrelevant and a reinforcement of the soap operaish, disease-of-the-week aspect of the movie. That it ends — spoiler alert! — with his telling Hannah’s story to the daughter seems to be meant to be a kind of resolution/absolution because it means he is becoming more emotionally engaged. Hurrah! The Holocaust seems a long way off, now that the movie has trotted out that favorite Hollywood trope of reducing inhibition and emotional detachment for therapeutic purposes. His pity may not be enough to effect Hannah’s salvation, but it works a treat with his own.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.