The Mind of the Past

From The American SpectatorO beautiful for patriot dream

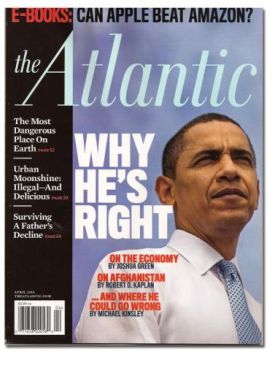

“Obama Makes History,” blared the headline in The Washington Post last November 5th. A few days later in the same newspaper, Robert Kaiser acknowledged this as “a statement of the obvious, but then asked, “What does it mean to make history?” A good question! Mr Kaiser thought that “History is made in two ways: By dramatic occurrences, often surprises, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989; and by the slow accretion of small changes over long periods.” The election of President Obama, as he saw it, combined both. Well, I agree that his election made history, but I would like to propose a third way in which history is made — particularly when it is the kind of history that appears in newspaper headlines. History is also made when people find something happening in the present that makes them feel good about something that happened in the past.

The newly-elected President, for example, made history not just by being elected but also because to the kinds of people who work as writers and editors at The Washington Post his election was in an important respect a repudiation of history — a part of history which made them feel guilty and ashamed. The repudiation made them feel better about themselves and their country and so in a way represented to them what the fall of the Berlin Wall did to a popular author of a couple of decades ago who wrote, oxymoronically, of “the End of History.” The End of History is history too. But it is interesting how much of what we call history in President Obama’s America is now history of this third kind. A fortnight after the election, Washington saw the re-opening, after three years of renovations, of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, which is full of it.

This museum has always had an interest in “social history,” though not necessarily of the type practised in universities, which usually involves a greater or lesser degree of Marxism, or the various sorts of neo-Marxist ideologies such as feminism or post-colonialism that are based on a Manichean division of the world into oppressors and oppressed. It is actively hostile to traditional and “great-man”centered interpretations of the past. The story is his-story no longer, but rather that of the oppressed peoples — whoever you like them to be — struggling for liberation. There is some, mostly unobtrusive history of this kind at the newly-reopened Museum. At one point, for instance, as part of the history of industrialization in the 19th century, a wall card tells us that

affluent Americans developed their own class consciousness. They promoted a sense of their entitlement through institutions they established and through the popular press which they often controlled. To justify their wealth when so many were poor, some misapplied Charles Darwin’s ideas on evolution, arguing that their rise reflected the survival of the fittest.

Here, “a sense of their entitlement” must refer to the quaint belief still harbored at the time by these “affluent Americans” that their wealth was actually their own and not ripped unjustly from the trembling fingers of the poor. The assumption that some are poor because others are rich and that the latter should be called on “to justify their wealth” — inevitably with some “misapplied” theory such as Social Darwinism — is a Marxian habit that few ideologues ever break themselves of, although it has never been one shared with the majority of Americans. Shouldn’t the majority also have a voice here, we wonder?

Well, it does in a way. For under its superficially more benign aspect at the NMAH, social history presents itself mainly as nostalgia. Nostalgia is to history as celebrity is to fame. Both are ways for ordinary people to expropriate things that are other, and that insist on their difference from the ordinary, and to make them, instead, matters for their own feelings to feed on. The British novelist, L.P. Hartley, once was famous for writing that “the past is another country: they do things differently there.” Not anymore. By assimilating history to nostalgia, we enable the present, in effect, to colonize the past and erase its differences.

That’s why the Museum of American History devotes so much of its exhibition space to the ephemera of pop culture. Here are to be found Carrie Bradshaw’s Mac Power Book from Sex and the City and Grandmaster Flash’s turntable as well as the original text of the Gettysburg Address and the flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star Spangled Banner.” By putting these artifacts on a level with each other, the Museum creates in the present a feeling of familiarity not with the reality of the past — which, as R.G. Collingwood long ago demonstrated in The Idea of History, is mental — but with its artifacts. That is: with the part of the past that is still present.

|

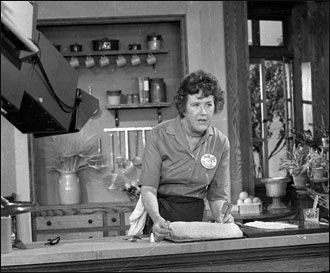

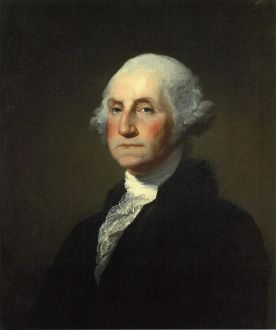

This creates the illusion for us that we still possess it, though at the cost of being unable to make necessary distinctions. Julia Child’s Kitchen is here, for instance, presumably because she was on TV. She was a part of our lives — at least if we are of a certain age — and we therefore feel a warm glow on being reminded of her reassuring presence. George Washington’s campaign chest and camp stool are here too but without much to suggest that he was of any more significance for American history than Julia Child.

The assumption that the existence of poverty requires those who are not poor “to justify their wealth” is a form of unexamined egalitarianism common to the late 20th and early 21st centuries and so fits in with those other contemporary crazes, less familiar to our ancestors, for celebrity and nostalgia. These are also egalitarian because they insist that our admiration for a thing gives us rights of equality with it — makes it somehow ours instead of its creators’ or the context in which it was created. The old-fashioned cash registers and the Radio Flyers here, just like the costume of the original C3PO from Star Wars, are the celebrity photographs of the past that make it our own. Before the renovation, there seemed something almost pleasingly tacky about going to the museum to see, preserved in a glass case, Dorothy’s ruby slippers from the film of The Wizard of Oz. These are still there, along with hundreds of similar officially-preserved souvenirs, but it soon begins to seem that you can take a good thing too far.

Where history as traditionally understood still exists at the museum, there is an attempt wherever possible to repatriate it to the present. The best thing by far about the renovation is that it includes an extensive exhibition on the top floor titled “The Price of Freedom: Americans at War.” Sponsored by Kenneth E. Behring, whose generosity was responsible for much of the museum’s face-lift, it gives a relatively straightforward account of America’s wars from the French and Indian to Desert Storm, though there is almost nothing about the war in Iraq of the last six years. Too controversial, I suppose. But controversy is also on display, especially in the part of the exhibition devoted to Vietnam — which was apparently nothing but controversy. I’m guessing that that’s what gets it the spread it has. It was on TV too, after all. The Korean War, by contrast, is barely mentioned.

Even World War II — still, obviously, very much “The Good War”so far as the Museum of American History is concerned — had its share of controversy, it seems. “In July, 1945,” one bit of the display informs us, “President Truman made his controversial decision to use atomic weapons.” But in July, 1945, the decision was not controversial. Only in recent years, as the circumstances in which the decision was made have faded from memory, has an air of controversy been projected back onto it. People are constantly being encouraged to look at the past with the sensibility of the present and never for a moment cautioned that there might be anything wrong with this.

To understand the past, you have to understand the mind of the past which once provided the context for all these dead artifacts. Once taken out of that context and deposited in a museum, they can only mislead those who have not taken the trouble to inform themselves about the context — even so much of it as that dry and boring list of facts and dates that the Museum director has told interviewers he wants to eschew. To make the past attractive, it seems, all that makes it the past has had to be taken out of it. But, then, why should we expect a celebrity-struck museum to do otherwise when academic history is quite as likely to be found filleting selected bits of the past from the circumstances that give them meaning in order to make it more palatable to a narcissistic public?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.