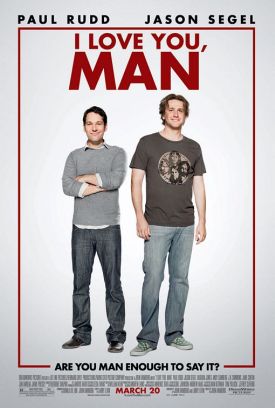

I Love You, Man

Director John Hamburg’s I Love You, Man, which he also co-wrote with Larry Levin, purports to be a movie about male friendships in middle age, but really it is an apologia for our culture’s extension of adolescence into middle age. The friendship under consideration here is between 30-something Los Angeles real estate agent Peter Klaven (Paul Rudd) and Sydney Fife (Jason Segel), a guy he meets at one of his open houses who cheerfully confesses that he has come only for the food. Recently engaged, Peter has been shamed by overhearing his fiancée, Zooey (Rashida Jones), tell a group of her girlfriends that “I think his mom’s his best friend.” Even younger his gay brother, Robbie (Andy Samberg), a fitness instructor, seems to know more about male-bonding than he does, while his dad (J.K. Simmons) woundingly says that Robbie is his own best friend. Naturally, Peter turns to Robbie for advice. Hollywood’s Magic Gay Guy is today what its Magic Negro was a decade or so ago.

Guided by Robbie, Peter goes on a series of “man-dates” to try to get himself some friends. Like the rest of the movie, these are not nearly so funny as we might have expected them to be. You’d think you would be in howls of laughter when Peter throws up over Barry (Jon Favreau), the husband of one of Zooey’s friends, or gets kissed by Doug (Thomas Lennon), who thinks he’s gay, but there it is. If you’re anything like me, you aren’t. Nor are Peter’s halting and embarrassing attempts to invent his own cool slang, which come out sounding more like Rob Schneider’s photo-copier guy on “Saturday Night Live,” the hoot you would expect. As a result, neither do you get quite the kick you’re supposed to get once Peter, having given up his quest, runs into Sydney.

Besides the fact that he cruises multimillion-dollar open houses for the food and the chance to meet rich divorcées, here are a few things you ought to know about Sydney. He is a huge fan of the aging Canadian rock band, Rush, and he enjoys both trying to play their music on his own electric guitar and acting like a teenager — which, compared to them, he almost is — at their concerts. He has a dog named Anwar Sadat (because, supposedly, he looks like the late Egyptian president) whose mess he refuses to pick up, much to the distress of several passers-by. He has a special chair, adjacent to various unguents and embrocations and in front of one of the many TV sets in his “man-cave” that he uses for masturbation. At an engagement party for Peter and Zooey and in the presence of their family and friends, he earnestly instructs the bride-to-be in the advisability of making herself more available for a particular act of oral sex.

If all this makes him sound like a less-than attractive character, that’s because he is. And if you think that that would be a serious drawback to a movie about friendship, it is. The odd thing is that Messrs Hamburg and Levin don’t know this. Either that, or they are under the impression that Sydney’s oafishness and immaturity makes him more lovable. Or, a third possibility, they just don’t care, since the point of Sydney is not really for him to be Peter’s friend but to be his lifeline back to the comforting world of immaturity and adolescent irresponsibility on the eve of his marriage. And if that seems unlikely, given Peter’s comparative maturity, they needn’t care about that either, since the lifeline is really for the audience, not for Peter.

The idea here is perhaps that a man needs a friend to supply him with an excuse to stop being a man and regress to adolescence. That’s why, at one level, the film is all about manhood. But it is a free-lancer’s manhood — manhood cut loose from its social dimension and the honor culture that goes with it and, therefore, something that kids are free to make up as they go along. “I’m a man, Peter. I have an ocean of testosterone flowing through my veins,” says Sydney on one occasion when he is confronted by a man who has stepped in his dog’s feces, which he leaves to foul the public footways on principle. Turning on the man aggressively and scaring him away, he blames “society” for trying to arrest his aggressive impulses. “The truth is we are animals, and we have to let it out sometimes.”

Later, after a similar confrontation with a body-builder, Sydney turns tail and runs for his life. So much for his lovingly tended aggressive impulses. There’s not even any attempt to hide the fact that his various rationalizations for bad behavior are merely nonsensical excuses for an adolescent delight in bad manners as a token of personal authenticity. In the end, we’re meant to think that Peter may have helped Sydney to grow up a little. “You called me on some of my issues,” says the latter as prelude to the inevitable, “I love you, man.” But the whole weight of both the drama and the comedy goes in the other direction

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.