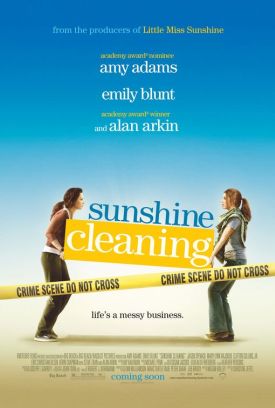

Sunshine Cleaning

If there’s such a thing as a money quote, the one in Sunshine Cleaning, a somewhat charming but ultimately unpersuasive movie by Christine Jeffs (Sylvia), comes near the end. Rose Lorkowski (Amy Adams), a single mother who has failed in her adult life to live up to the social prominence she seems to have enjoyed in high school, has just had a very bad day. In a moment of extreme exasperation, she indulges herself in an outburst to a sympathetic but far from intimate acquaintance, a one-armed clerk in a cleaning supply store called Winston (Clifton Collins Jr.). “I am good at getting guys to want me,” she tells Winston. “Not date me or marry me but want me; I’m really good at that. That and cheering. I was really good at cheering.”

Winston, whom we naturally expect to be destined himself to a romance with her until Ms Jeffs runs out of film, dryly replies: “Cheering’s good.”

“Yeah, but not as lucrative as you’d think.”

It’s funny and it’s moving, but I’m afraid it’s not true. Oh, it may be true for her character in the movie, but it’s only an indication of a false note in that character. This is the idea that there is some special fatality in her sexiness that makes men not want to commit to her — even so far as just to want to “date” her. That’s probably how it looks to her, but it is the movie’s job to supply the corrective to that point of view. Everybody knows, these days, that the world is full of men who don’t want to commit. This is not the curse of Rose but a natural and inevitable product of the culture we have chosen for ourselves in the wake of the sexual revolution. Why would men want to commit when they can get the thing for whose sake they have always committed, up until 40 years ago, without committing?

In other words, Rose is just feeling sorry for herself, but in a way that (I imagine) many single women — and especially single mothers — with unhappy love-lives often are. The feeling may increase the movie’s potential market among this particular demographic, but those with a little more detachment will see the problems with magnifying her own troubles until she becomes the most signal sexual victim in the known universe with a very particular bone to pick with God for thus singling her out. As a way of denying her own responsibility for carrying on an affair with her high-school boyfriend, Mac (Steve Zahn), now a police detective and married to somebody else, fatal conceit might have some promise, but Ms Jeffs doesn’t know how to exploit it. Instead, she gives her heroine yet another grudge against fate in the long-ago suicide of her mother.

Yet insofar as this traumatic memory is what reinforces the bond with her ne’er-do-well sister Norah, played by the excellent Emily Blunt, whom I have admired since her breakthrough role in My Summer of Love (2004), I don’t mind it so much. The character of Norah and the relationship between the two sisters are the two best things about the movie and almost make up for its many deficiencies, including its taking Rose and Rose’s many disappointments more seriously than they deserve. The two sisters go into business together cleaning up crime scenes — which, as Mac explains to Rose, is a job that will pay well enough to enable her to send her young son, Oscar (Jason Spevack) to private school. This she feels she has to do because Oscar is “acting out” and getting into trouble at school and, like so many parents these days, she blames the school. Clearly, Oscar is well on his way to becoming, like his mother, a victim of fate.

Sunshine Cleaning

has been much criticized for being so obviously derivative from Little Miss Sunshine of 2006, the quirky indy hit that was bound to spin off such imitations — even though most of them would probably have been more artful and less obvious than to use “Sunshine” in the title and employ Alan Arkin to play a very similar grandpa to the one he played in that picture. A.O. Scott in The New York Times takes this almost as a personal affront, though it does give him the opportunity to make the rather witty joke that, instead of being called Sunshine Cleaning, the movie would have been more accurately named “Sundance Recycling.” But to me its imitative quality is less of a black mark against it than its thematic confusion and its multitude of narrative loose ends.

The other main point of similarity between the two pictures, for example, lies in Rose’s self-help and motivational agenda, which has her repeating a sentiment that might have been approved by Greg Kinnear’s character in Little Miss, “You are strong. You are powerful. You can do anything. You are a winner.” Once it is established that she is none of these things, however, this theme is simply dropped, along with Oscar’s further adventures in socialization, Rose’s relationship to a more successful high school pal, grandpa’s get-rich-quick schemes, Norah’s sort-of lesbianism and Rose’s prefigured romance with Winston. Ms Jeffs doesn’t even think it worth explaining why Winston has only one arm. All this is very annoying, of course, but insofar as you can concentrate on the two sisters, you will find the movie to be more than occasionally entertaining.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.