Taken

As I was perusing the website of The New Republic the other day, I came across this sub-headline to Christopher Orr’s review of Monsters vs. Aliens: “Enjoyable enough if you’re under 13, or have the taste of someone under 13.” Ha ha. But wait a minute. Isn’t there supposed to be some news value in a headline? Aren’t you supposed to say “Man bites dog,” not “Dog bites man,” if you want people to read on? Is there anyone on the planet who doesn’t know at least as well as Mr Orr and long before stepping into the cinema to see it that Monsters vs. Aliens is going to be a movie made for the sensibility of a 13-year-old? We could go further and ask if there is anyone who doesn’t know that 90 per cent of Hollywood’s mainstream product is made for 13-year-olds? The surprise, I guess, the unexpected element in his story, is that he should treat anything so predictable as a surprise.

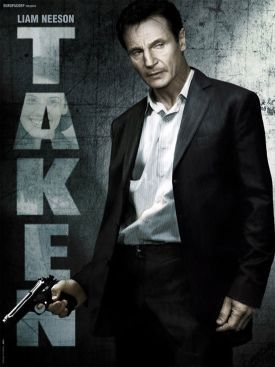

Well, here’s a real surprise. If you have come to think, as I have, that the CIA is just a dysfunctional agency in the business of producing useless intelligence, getting things wrong, offering sinecures to the likes of Valerie Plame and engaging in bureaucratic backbiting and the undermining of elected authority, it turns out not to be true. Not according to Hollywood, anyway. All true patriots will rejoice to learn from Taken that the Agency, or the Company, as those of us in the know refer to it, is really in the business of turning out superheroes who have the ability to right the wrongs of the world single-handedly and against overwhelming odds while biffing the dozy, incompetent and corrupt French in their own country into the bargain. The fact that the movie is directed by one Frenchman and written and produced by another suggests a deep psychological conflictedness that, alas, doesn’t do anything to enliven this dull thriller.

What does is — you’ll never guess — car chases! Of course I ironize. Christopher Orr might not be able to guess it, but the rest of us will without difficulty, particularly if we are familiar with the cinematic oeuvre of Pierre Morel and Luc Besson, director and writer-producer respectively, who earlier collaborated on the Transporter films. In addition to the car chases, of course, there are the usual superhero antics. You know what I mean. The craggily handsome hero — here played by Liam Neeson — walks into a room full of men with foreign accents and guns who are all eager to kill him, and, in a matter of seconds, he kills them instead. All of them. In Taken he does this, several times, in order to rescue a pure and virginal maiden — his own daughter (Maggie Grace) captured by Albanian white slavers in Paris — in order to make up for years of parental neglect while he was being a superhero for the CIA instead of freelancing, as he is now.

Of course, like all superheroes, he is incredibly lucky. Talk about all the breaks going a guy’s way! With only 96 hours to rescue his daughter before she disappears forever, he finds that the first pimp he approaches, or who approaches him, is one of the Albanian gang of kidnappers. This person then inadvertently leads him straight to where a bunch of the kidnapped girls are kept, where he immediately finds one of them with his daughter’s jacket. He extracts this drugged girl from her place of confinement, killing any number of those who have been charged with guarding her and the others, and takes her away in a car that, in the ensuing chase, is soon riddled with bullets, all of which fortunately miss both him and the girl. With his skills in pharmacology and medicine he then revives the girl and finds out from her where the bad guys hang out before proceeding to kill another house-full of them — all except one, whom he tortures for the information he needs to find his daughter.

After that it gets a bit complicated, but you’ll not be surprised to learn that his incredible luck holds — as does the incredibly bad luck of yet another boat-load of bad guys. The surprising thing — at least to me — is that the scenes of torture are meant to make our hero more, not less sympathetic to us. The script even allows him to joke about it as he turns on the juice to shock the bad guy strapped to a chair. “You know, we used to outsource this stuff,” he tells him meditatively. The trouble was that the power grids in the Third World countries that got the contracts were unreliable. Here in France, he tells him, “You either give me what I need or this switch will stay on until they turn the power off for lack of payment on the bill.” Of course, the guy gives him a name, Vincent St Clair, but can give him no address, even under torture. He doesn’t know, he says desperately. The good guy replies: “I believe you” — and then, as he goes out of the room, he turns the electricity back on. “But that won’t save you.”

Ouch! This, says the New York Times reviewer Manohla Dargis in a review headed “Vigilante Daddy Avenges Kidnapping,” is “a repellent scene” which leads her to the further observation that “swarthy Europeans and Arabs may still be the villains du jour at the movies, but the Americans, including those with inexplicable Irish accents, are, alas, catching up.” Like President Obama, in other words, Ms Dargis thinks that we don’t have to choose between our ideals and our security. And nobody’s going to tell either of them any different. Thus, she simply refuses to accept the central dramatic premiss of the movie — surely not that unbelievable when compared to most of what it is asking us to swallow — namely that, without the torture, the L.A. princess would have been on her way to some wicked sheikh’s seraglio post haste. Only by torture (not to mention all the indiscriminate killing) is daddy able to save her. And this makes him a “vigilante” and a “villain”? Well, in that bastion of enlightened progressivism, the New York Times, I guess it does.

Presumably, in his position, Manohla Dargis would have stuck to her high-minded principles and fed the virginal princess to the big bad wolf. Come to think of it, that wouldn’t be an all-bad idea. At least daddy might have left her in the company of the wicked sheikh for a while before rescuing her — and killing him — in the hope that she would come out of the experience a little less spoiled and princessy and a little more humble instead of being launched, more or less immediately upon rescue, into her career as a celebrity singer — again with daddy’s never-failing help. But then I suppose that superheroes must be expected to spawn other superheroes or they’re not really superheroes. The 13-year-olds would protest.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.