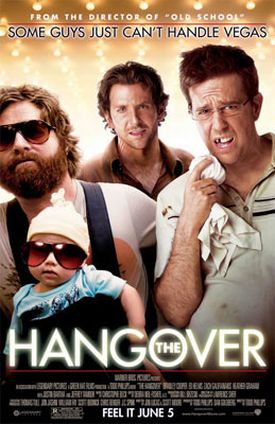

Hangover, The

The first thing to realize about Todd Phillips’s The Hangover is that it contains no actual hangover — not in the sense that the term is usually understood. Or at least as it was understood in the days of my youth when hangovers were not so unfamiliar to me as they are now. That sort of hangover, in case the word has changed its meaning without my realizing it, was the kind that comes in the morning, on waking, from having drunk too many alcoholic beverages the night before. Mostly it involved headaches, sensitivity to light, a dry mouth and, in really bad instances, sickness to one’s stomach. The hangover in this movie is not of that kind, nor is it recognizable as belonging to the same genus as literature’s most famous example, that of Kingsley Amis’s Jim Dixon:

He lay sprawled, too wicked to move, spewed up like a broken spider crab on the tarry shingle of the morning. The light did him harm, but not as much as looking at things did; he resolved, having done it once, never to move his eyeballs again. A dusty thudding in his head made the scene before him beat like a pulse. His mouth had been used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum. During the night, too, he’d somehow been on a cross-country run and then been expertly beaten up by secret police. He felt bad.

I keep meaning to write a piece attempting to explain why the world had to wait until 1954 and Lucky Jim for an elegantly comic literary treatment of the after-effects of drunkenness, but I haven’t yet got around to it. Hint: it has to do with honor. And, of course, shame.

Shame, as it happens, is also what’s missing from the movie of The Hangover. The physical grossness of the hangover’s symptoms stand for, or used to stand for, the moral lapse of overindulgence. Needless to say, those days are long past. Now, so far from being a badge of shame, being drunk out of one’s mind is a badge of honor. As Mike Tyson, who makes a cameo appearance in the movie so elegantly puts it, “we all do dumb s*** when we’re f***** up.” And dumb s***, as everyone knows, is funny. But if the purpose of imbibing is to be funny for the benefit of others and ourselves, little or no actual alcohol need be involved. The point of drinking nowadays is simply to get smashed as quickly and efficiently as possible, and for that drugs are a much better way to go.

That, at least, is the discovery of Phil (Bradley Cooper), Stu (Ed Helms) and Alan (Zach Galifianakis) who are helping Doug (Justin Bartha) celebrate his bachelor party in Las Vegas when Alan — the odd man out of the quartet in several, faintly disturbing ways — laces their Jaegermeisters with Rohypnol, familiarly known as “roofies” or “the date-rape drug,” under the impression that he is only adding “ecstasy” to the fun. Slow dissolve. The next thing they — and we — know is that there is a tiger in the bathroom and a baby in the closet; Stu is married to a stripper and minus a lateral incisor while Phil has a hospital bracelet on his wrist; they find themselves in charge of a police cruiser that they have apparently valet-parked the night before and, when they finally find their car, there is a naked Chinaman in the trunk. Oh, and Doug is missing. In short, the only real symptom of this hangover that is of any interest is amnesia, and amnesia looks a lot funnier than people being sick.

The fact that no one has any memory of how any of these things could have happened is just about the whole of the comic scenario — and, besides being funny, it dispenses with the need for any joined-up cinematic story-telling of the type that I tend to prefer in movies but so seldom see anymore. But this movie gets more comic mileage out of keeping us in the same state of ignorance as the boys themselves. Like them, too, we only get reminded of the highlights of the night, not how they got from a to b, which wouldn’t have been so funny. For the highlights are quite funny. The confusing and equally hilarious events of the following day eventually reveal, though in no particular order, how some but not all of the surprises of the morning came to be, and add some new ones.

For instance, the naked man (Ken Jeong) appears to be under the impression that our heroes owe him $80,000, and he is involved with some very scary people who seem determined that they shall pay it. Also, the rightful operators of the police cruiser are sore about having mislaid it and arrange to have the hung over trio (Doug is still missing) tasered by a group of school-children on a field trip. “You can’t just tase people because you think it’s funny,” says one of the gang indignantly. “That’s police brutality.” It’s also movie comedy as we know it today — because, I guess, it is like extreme drunkenness in allowing for the presentation of people suffering painful and undignified lapses from rational human behavior without any rational context to make sense of them, or the need for any slow-moving narrative exposition. Craziness is its own justification.

As a sort of po mo joke at the very end of the film, one of the guys discovers a camera on which snapshots of their wild night have been taken, and we see these over the close credits. But the photos don’t fill in the gaps at all, as advertised; instead, they merely add new highlights and — occasionally obscene — comic non sequiturs to the phantasmagoria of the night’s adventures. Oddly, there are what seem to be intended to be serious moments in the midst of this laff-riot. Stu may not be married to the stripper (Heather Graham) after all, but he seems to like her a lot better than he does his shrew of a girlfriend, Melissa (Rachael Harris). The masculine bonding is, in the first place, an escape from feminine constraints — to the point where there are coy but nervous little references to homosexuality — but the happy ending implies that, except for Alan, they have all returned to civilization with their masculine confidence and assertiveness restored. I wonder if that’s a po mo joke as well?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.