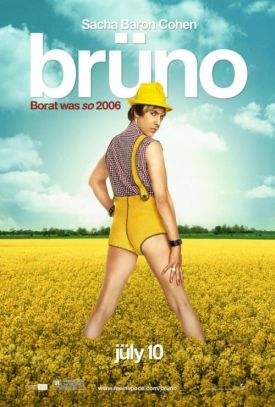

Bruno

Bruno — the official umlaut over the “u” is, as in certain heavy metal pop groups, merely decorative and non-functional and so will be ignored here — may be the funniest as well as the most offensive movie since Team America also captured both titles a few years ago. As always, its star, Sacha Baron Cohen, a.k.a. Borat, a.k.a. Ali G, is an equal-opportunity offender, but his Bruno is a little more offensive and a little more interesting than Borat was because he is a more consistent character. Borat was just a bit too knowing. Though ostensibly a naif, he often stepped out of character whenever he needed to provide the nudge and the wink required for us to get the joke. As I noticed at the time, Borat couldn’t be mistaken for a real Central Asian peasant by anybody. He was an obviously hip cosmopolitan who was dummying up as an excuse for saying outrageous things. Bruno doesn’t do that — partly because he is supposed to be a hip cosmopolitan, albeit an unnaturally stupid one, so that his creator in portraying him remains mostly in character.

Or, to be strictly accurate, in caricature. For Bruno’s stereotypical homosexuality is the only thing about the movie more salient than his stupidity. I find it interesting that the gay community can apparently not quite decide what they think of him. The headline to a New York Times article about the film about sums it up: “A plea for tolerance in tight shorts — or not.” For the record, it is not. The Times just can’t quite get its editorial mind around the idea of a movie with a gay hero which is not “a plea for tolerance.” Both Bruno and Bruno take tolerance for granted — it’s one way in which the character demonstrates his stupidity — and then promptly test its limits to the point where some gay people may find him embarrassing, to say the least. The New York Times article reports on this ambivalence among gays.

“Some people in our community may like this movie, but many are not going to be O.K. with it,” said Rashad Robinson, senior director of media programs for the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. “Sacha Baron Cohen’s well- meaning attempt at satire is problematic in many places and outright offensive in others.” Holding the opposite view are people like Aaron Hicklin, the editor of Out magazine, who said he plans to put Mr. Baron Cohen on the August cover. “The movie does something hugely important, which is showing that people’s attitudes can turn on a dime when they realize you’re gay,” Mr. Hickland said. “The multiplex crowd wouldn’t normally sit down for a two-hour lecture on homophobia, but that’s exactly what’s going to happen. I’m excited about that.”

The Times’s own take on the film is typically “nuanced” as it notes that, “ultimately, the tension surrounding Bruno boils down to the worry that certain viewers won’t understand that the joke is on them and will leave the multiplex with their homophobia validated.”

Or maybe — gulp — they’ll realize that the joke isn’t on them, or at least not just on them. It seems to me that the target of the film’s satire is as much homophilia as it is “homophobia.” The official culture’s attempt to enshrine what it weirdly calls “tolerance” — isn’t the whole point that we’re supposed to approve and celebrate “diversity,” and not just tolerate it? — as the principal, if not the only, virtue in the catalogue of morality can be at least as laughable as those who ignorantly demonize homosexuals. Indeed, rather more so, since some, at least, of the alleged homophobes can be understood as giving expression not to “hatred” of homosexuals but to an age-old shame reaction that was once evoked in nearly everyone by public sexual displays. The banishment of such shame from our culture on ideological grounds over the past 40 years or so has, I think, produced tragedy as well as comedies like this one.

The central conceit of the film is that the title character, an exaggeratedly camp Austrian fashion-commentator, loses his job as the presenter of “Funkyzeit mit Bruno” on Austrian TV and comes to America to make his fortune (as he hopes) on the world stage. After a few reverses, he decides that to be a top celebrity like Tom Cruise or John Travolta or Kevin Spacey, you have to be, as he supposes them to be, a heterosexual and that he must convert. His attempt to do so produces a few yucks at the expense of clergymen and others who specialize in gay-conversion as well as the macho culture of the military, martial arts practitioners, hunters and wrestling fans. His attempt to join a heterosexual swingers’ party and subsequent ignominious escape from an amazing naked blonde female who is trying to beat him with a belt may be the funniest thing in this funny movie.

But before that he has also turned his satirical sights to such bi-partisan targets as the superficiality of the fashion world, celebrity do-gooders and their adoption of babies from Africa — he trades an iPod for his, to whom he gives the “traditional African name” of O.J. — stage parents, and gay promiscuity. Incidentally, Sacha Baron Cohen, the real Bruno, is also very brave, at one point interviewing in character a Hezbollah terrorist and avowed hostage-taker and advising him and his fellow terrorists to “lose the beards, because your King Osama looks like a dirty wizard, or a homeless Santa.” He also plays with racial stereotypes in front of a black audience, engages in gay sexual activity in front of an audience of wrestling fans and creeps naked into the tent of a heavily armed heterosexual in the middle of the night pleading that a bear has eaten all his clothes.

There are also jokes about “Austria’s black sheep, Adolf Hitler” — “For the second time in a century, the world had turned on Austria’s greatest man, just because he had the bravery to try something new” — which could get him lynched by a gathering of progressive pacifists. At one level, this is just more of Bruno’s stupidity, but he is stupid not just as Bruno but as a would-be celebrity of a kind which says things almost as stupid. The point of this scattershot approach to the pieties of left and right alike seems to me to be to find such boundaries of taste and propriety as still exist, though often subliminal and unacknowledged, in a culture which has officially banished such things — and then to cross them. The film is a reminder of how hard it is to be “transgressive” anymore and so, in a weird way, may even be regarded as a back-handed sort of plea for more boundaries, like a misbehaving child’s implicit plea for more discipline. At least that’s how I prefer to see it, since it allows me to feel less guilty about laughing at it as much as I did.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.