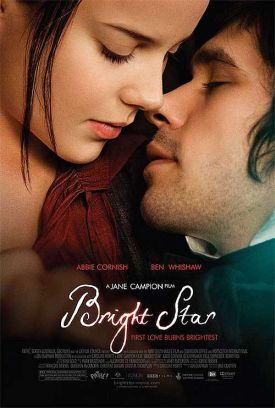

Bright Star

On the line of the New York Times review of Bright Star which is normally reserved for descriptions of a movie’s suitability for children, the reviewer has written that the movie is “perfectly chaste and insanely sexy.” I think what may have been intended, however, is “perfectly sexy and insanely chaste.” Modern culture so often displays a shocking lack of imagination in coming to terms with the people of previous centuries, as if it can’t quite forgive them for not being just like us. Why even comment on the chastity of the relationship between John Keats — who, for victims of American public education, was an English poet whose (formerly) famously short life was lived between 1795 and 1821 — and his fiancée, Fanny Brawne? Do we imagine that, as an unmarried couple in 1819, they could simply have chosen instead to have been “sexually active” — not a term that existed at the time, by the way — and moved in together?

This is not just the reviewer’s obtuseness but also, at least to some extent, a question arising out of Jane Campion’s screenplay and Jane Campion’s direction and the fine and sensitive portrayal of Fanny Brawne by Abby Cornish. It really does juxtapose powerful feelings and the negative immensity of their being frustrated of their natural outlet. The problem is that conceiving of the relationship between Keats and Fanny in this way emphasizes the film’s 21st century perspective. Everything in it naturally centers itself around the moment where Fanny is made to say, “You know I would do anything. . .” and Keats replies: “I have a conscience.” Their chastity is the thing we focus on because it is the thing about their lives and relationship that seems most strange and therefore remarkable to us. More remarkable, even, than the fact that the young man involved was, at least in terms of his potential, one of the half-dozen greatest English poets and was dying, not yet having reached the age of 25, of tuberculosis.

Even if, in taking us back to the years 1819 and 1820, the film-makers had somehow caught in their lens a humble medical student called John Smith, rather than John Keats, but one who had the same girlfriend and the same illness, the absence from their relationship of sex, in the modern sense, is unlikely to have been the first and most important thing on either of their young minds. They would have had to take that for granted, and so their psychic energies would have been somewhat differently focused. It’s not that there would have been no sexual longing, nor even that the movie is no good for concentrating on sexual longing to the exclusion of much else and so of failing to see its characters as they would have seen themselves, and as their contemporaries would have seen them. But it does seem to have missed an opportunity to slip the surly bonds of hyper-modernity to show us something we would not otherwise be able to see.

There has long been a division among Keatsians between pro-Fanny and anti-Fanny factions, the latter seeing her as a bit of a flirt, a bit of a flibbertigibbet, trivially-minded and intellectually light of weight — in short, as an unfit consort for one of the poetic immortals. She is supposed to have brought the great man more heartache than joy and more distraction than inspiration during the tragically brief period of his greatest productivity. The feminist tendency of the criticism of the last 40 years or so, however, has championed her finer qualities, and Miss Campion belongs, as we might expect, emphatically to the pro-Fanny faction. Indeed, her movie not only presents Fanny in the best possible light but is utterly Fanny-centric — so much so that we may almost forget about Keats (Ben Whishaw) as one of the greatest of the English poets, and see him only as Fanny’s frustrated boyfriend.

In a way, however, that’s almost inevitable in a movie like this. Or in any movie. Telling the human story of famous people on film produces such a powerful imaginative effect that the human story is often, if not always, all that is left of them. The word “human,” by the way, should be seen at least partly as it was in the pre-sexual revolution period as a euphemism for “sexual.” The reason why these two incidentally sexual beings became famous in the first place, which has to do with the kind of work they did rather than the kind of people they were, can rarely produce such an impression. Certainly it doesn’t in Bright Star. Miss Campion tries here and there to give us a cinematic rendition of bits of Keats’s poetry, and there is a complete recitation by Mr Whishaw of the “Ode to a Nightingale” over the closing credits — not the best of her ideas, it seemed to me — but I fear that the poetic effects are likely to be too subtle to register on a movie audience.

The anti-Fanny faction is represented here by Keats’s best friend, Charles Armitage Brown (Paul Schneider), who is shown as being himself a disappointed aspirant for Fanny’s attentions and who subsequently gets the Irish housemaid pregnant. That soap-opera touch conspires with the probably unavoidable tendency to a disease-of-the-week style presentation of the consumption that kills Keats’s brother Tom (Olly Alexander) before killing him, and together they push the love story itself in the direction of the banal. Miss Campion deserves a lot of credit for resisting this inertia of the medium and keeping things so tastefully and charmingly arranged and beautifully photographed that, leaving aside its anachronistic emphasis, it is quite enjoyable to watch and must produce a moving effect on all but the hardest of hearts.

The movie is named for the greatest of Keats’s sonnets, which goes like this.

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art —

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors —

No, yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillowed upon my fair love’s ripening breast —

To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever — or else swoon to death.

Like the “Ode on a Grecian Urn” — which would thus have been a better choice than the “Nightingale” for its featured position — this is a meditation on the unbridgeable gap between human (including sexual) feeling and its representation in art — which appears here as “nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite” (i.e. Hermit) who shares eternity with the “stedfast” star. But for all the beauty and finely evoked feeling of her film, Miss Campion doesn’t seem quite to be able to find a way to register the irony of that same tragic — and tragically timeless — divergence, which is what drives her back on the less compelling and less historically accurate theme of sexual frustration. All the same, the movie does well what movies can do well and is likely to provide an enjoyable couple of hours, especially to those who are, like me, sentimentalists about English poetry.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.