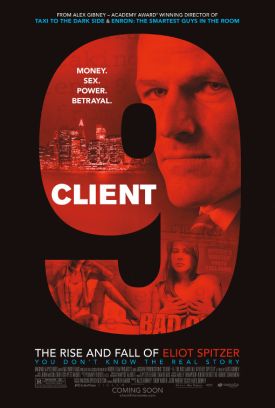

Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer

Alex Gibney’s Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer begins with a portentous saying about how mankind occupies the middle ground between angel and animal. This is the movie’s way of suggesting that its subject, the disgraced former governor of New York who got caught patronizing a high-priced “escort” agency, was, or is, a little of both himself. This, of course, meshes nicely with Mr Spitzer’s own rather comical self-importance in speaking of his downfall as “a Greek tragedy” and comparing himself to Icarus who, flying too near the sun, was brought down by “hubris.” This might have sounded a bit better coming from someone else, but not a lot. Either way, the hyperbole is a smoke-screen of attempted human interest to mask an underlying political purpose: namely, the rehabilitation of Mr Spitzer, who is now co-hosting a talk-show on CNN with Kathleen Parker, by casting him as the victim of a conspiracy to effect his ruin by Wall Street fat cats and Republican dirty tricksters.

In this it is also like Mr Gibney’s telling us the story of how, as a boy, little Eliot would play Monopoly with his property developer father and cry when the old man bankrupted him. So that’s why Attorney General and later Governor Spitzer was such a hard-ass. Perhaps, too, that’s why he felt he had to go looking for love in strange places — and away from home. No wonder, then, if he told one of his Wall Street targets that “You and I are at war. . . I will destroy you” — ” I hope I didn’t say that” he says with a laugh to the camera — and that his subordinates in the attorney general’s office used to say that the boss’s evil twin “Irwin” had reported for work that day when he was in one of his especially hard-charging phases. All these things are hinted at, rather than made explicit in Client 9, but its psychologizing is still meant to convey the illusion of understanding and so make us forget how little need there is, except politically, to make such a production out of accounting for some pretty commonplace vices and character flaws.

But the purpose behind the documentary is also to make the story it has to tell a heroic as well as a tragic one: the story of a good man, once known as “the Sheriff of Wall Street,” who just might — as it is hinted more than once by the film and not denied by Mr Spitzer — have saved us all from the financial catastrophe that followed his departure from the governor’s mansion in disgrace by only six months. Mr Gibney relies on the fact that, since then, it has presumably become much easier to believe in the angelic part of Mr Spitzer’s career, not apparent to everyone who had dealings with him at the time, and in the retrospective justification for his legal assault on those too-highly-paid Wall Street types, especially Maurice, “Hank,” Greenberg of A.I.G., who have come to seem well-deserving of his attentions.

Yet what if Eliot Spitzer was neither angel nor animal but just a flawed human being? Obviously, it would make a less compelling story that way, but it would also rob it of what every political documentary needs— and what documentary is not political these days? — namely, a satisfyingly lurid set of villains. Presumably they are midway between devils and animals. So we shift back and forth between these men — in particular Mr Greenberg, Ken Langone and Joe Bruno all of whom speak of him (as it were) between gritted teeth and so are supposed to damn themselves out of their own mouths — and what the film can hardly fail to point to as the sleazier side of Mr Spitzer’s life as patron of high-priced prostitutes. “I’d like to think I’m not a vindictive person. And a basic tenet of my faith is forgiveness,” says Mr Langone. “The most harm that Eliot Spitzer’s done to me is I’m defying my faith. I can’t forgive him. I should, but I can’t.”

What inspired Mr Langone’s unforgiving wrath was Mr Spitzer’s pursuit, as attorney general, of New York Stock Exchange chairman Dick Grasso back in 2004 for making more money than he thought him entitled to. Mr Langone, the founder of Home Depot, was chairman of the Exchange’s compensation committee at the time and so also was one of Mr Spitzer’s targets. Mr Gibney suggests without making the allegation directly that Mr Langone had his nemesis under surveillance and must have been the one that tipped off the Feds about his hooker habit. They, in their turn, are thought to have been working under the political direction of the Bush administration’s justice department in bringing a prosecution against the escort agency, the Emperor’s Club, only for the sake of leaking to the press the identity of Client 9 — then-Governor Spitzer. The bad guys also include Roger Stone, a bizarre figure on the fringes of Republican politics who is assumed to have had a hand in Spitzer’s downfall and himself lends credence to the allegation by speaking confidingly to Mr Gibney’s camera as a man who knows more than he cares to say.

Having the kind of guy, like Mr Stone, who patronizes swingers’ clubs speaking for the opposition is meant to put a certain perspective on Mr Spitzer’s sins. But there is something stomach-turning about prostitution that Mr Stone’s exotic lifestyle can’t compete with. For some, the highlight of the film will be Mr Gibney’s interview with one of the hookers — not the famous one, variously known as Ashley Younomis, Ashley Dupré or Victoria. She went on to a brief celebrity before fading from view, but Client 9 is more interested in one of the Emperor’s Club girls who calls herself Angelina (not her real name) and who apparently saw a lot more of Mr Spitzer than Ashley-Victoria did. She has written up her account of him to be delivered by an actress to the camera. Angelina thus vicariously tells us that, on turning to prostitution, she found that she was treated better by the Johns than by most other guys she knew, so that while she was on the game she “stopped dating in the real world” as she engagingly puts it. Her standards in men were raised by screwing for money, she says, so you can see why she regards the “stereotyping” of prostitutes as unfortunate.

But doesn’t her anonymity tell you a lot more than her exculpatory account of Mr Spitzer as a decent guy who, contrary to reports, never left his socks on when he did the deed of darkness with her? The woman whom, I suppose, we must call the “Madam” of the Emperor’s Club, Cecil Suwal, is also interviewed on camera but under her real name. Not surprisingly, she regards her arrest on prostitution charges as monstrously unfair, noting that when the fuzz came to her door to close down the Club it was to her as if they had come for her children — of which she appears to have none. She herself was only 23, however, and the consort of the real boss of the Emperor’s Club, Mark Brener, who got two-and-a-half years in the pen as opposed to her six months. Mr Brener does not appear on screen.

Not that Eliot Spitzer himself engages in such special pleading. On the contrary, he tells his interviewer that “I did what I did and shame on me. I brought myself down; I’m not going to blame others.” But in the circumstances this sounds less like manly contrition than just another bit of moral posturing. If he really felt that it was his own fault and were properly ashamed, would he have sat down for five separate interviews with Alex Gibney to simper and hint of the powerful forces arrayed against him? “After speaking to a number of folks and talking with Alex about what he intended to do,” he told David Carr of The New York Times, “I got the sense that he was going to tell a story in a truthful and straightforward manner and I thought I could make a contribution.” Or, in translation, “I thought his self-consciously warts-and-all portrayal would make me look as good as it’s possible to make me look now, and it will both aid in my rehabilitation as a TV talk-show host and bring confusion to my enemies.” I hope you enjoy your part in all this if you go to see it.

Don’t ask me how or why Karen Finley, the famed “performance artist” and NEA grant recipient turns up to add her two-cents’ worth of sexual sagacity to Client 9, but when she does she tells Mr Gibney’s camera that “we want our political people to be god” — and so are presumably disappointed when they turn out not to be gods. This is another example of the movie’s “writing up” and significance-mongering on Mr Spitzer’s behalf. But I don’t think we want our political people to be god. I don’t think we want anything of the kind. We simply want our public servants to be men and women of what used to be called good character. Mr Spitzer’s career is evidence both of that lingering expectation and of the unlikelihood of its being met these days.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.