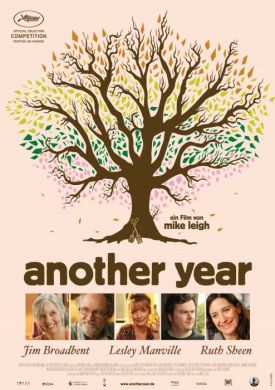

Another Year

Perhaps the most significant moment of Mike Leigh’s Another Year comes near the beginning when we see the great Imelda Staunton (Vera Drake) in a cameo role as one of the abandoned souls whom the film’s heroine, Gerri (Ruth Sheen), spends her work days as a therapist talking to. Miss Stanton’s character, Janet, has been having trouble sleeping, and Gerri is trying to probe gently beneath her embittered emotional surface for the causes. “What’s your happiest memory?” she asks as one of a series of questions trying to get at the invisible standard of comparison that is making Janet’s life so miserable. Janet either fails to understand these questions or refuses to answer them until Jerry asks, gently, “What is the one thing that would improve your life — apart from sleep?”

“Different life,” says Janet between clenched teeth, using as few words as possible.

We see no more of Janet in the film — though another character later becomes her male counterpart — nor is any further account offered by Mr Leigh for her unhappiness. He is unconcerned with where it comes from or what it leads to, as if he himself partakes in his character’s fierce determination to keep such knowledge from the world and instead hoard her grievance, whatever that might be, all to herself. We soon realize that he is starting as he means to go on, too, for neither are we allowed any more than the slightest glimpse of what T.S. Eliot once called (in the context of explaining what he called the “artistic failure” of Hamlet) the “objective correlative” for the problems of the film’s other emotionally crippled or otherwise unhappy characters — principally Mary (Lesley Manville), Ken (Peter Wight), Ronnie (David Bradley), Carl (Martin Savage) and Jack (Phil Davis).

You’ve got to wonder if the unhappiness of all these people is represented in the film only in order to point a contrast with the happy marriage of the couple at its center, Gerri and her husband, Tom (Jim Broadbent), whose easy companionship is symbolized by their labors on the family’s “allotment,” or state-allocated garden plot, where we see them performing seasonal chores in each of the film’s four sections. Like Sally Hawkins’s Poppy in Happy-Go-Lucky, (2008), Tom and Gerri are an island of happiness in a sea of discontent and even misery. Mary and Ken, for instance, are both family friends who seem to bask in the happiness of Tom and Gerri as if it might be catching. Both are both lonely and drink too much and, although on the one occasion when we see them together Ken seems interested in romantically pursuing Mary, she runs from him as from an image of her own unhappiness.

Ronnie, Tom’s recently widowed brother who still lives in the little family row-house in the industrial North, whence Tom has migrated to university and then to London to work as a geologist-engineer, is as taciturn and obscure as Janet. Carl, Ronnie’s son, apparently hates him — and pretty much everyone else. We do know that, long ago, during the Clough “glory years” (see Tom Hooper’s The Damned United of 2009), father and son never missed going to a Derby County football match together, but now they are estranged, again for no known reason. Carl is one of those Mike Leigh characters, like Eddie Marsan’s unforgettable driving-instructor, Scott, in Happy-Go-Lucky, whose mysterious state of boiling rage is constant and constantly boiling over. “The question is, will he turn up?” — that is to his own mother’s funeral. “He’d better,” replies Ronnie ominously. In the end he does, but only as it is ending, which gives him yet another grievance against his father, for not making the crematorium hold the service until he got there.

Gerri says at one point about Carl: “He was such a lovely kid, full of fun,” to which his father replies with what appears to be genuine wonder: “Was he?” Later on, Mary says to Ronnie: “Do you know Ken?”

“Yeah,” says Ronnie.

“He’s a bit weird,” says Mary.

“Is he?” says Ronnie — perhaps to signify that Ken is no more weird than he, or anybody else for that matter.

Many, no doubt, will consider Mike Leigh’s own emotional reticence in denying us further information about these characters a serious or even fatal flaw in the film, but I think that it is one of its strengths. He also denies us, in other words, the illusion of knowledge and therefore control, the easy assurance to be derived from the sort of explanations in which a therapist like Gerri might be expected to specialize. And not only are there no psychological explanations but no political, ideological, sociological or theological ones either. All the film’s sad emotional inequalities remain as unaccounted-for as any of the other sorts of inequalities that continue so to vex us in a world where so many of us have come to expect the kind of happiness that Tom and Gerri alone, here, have achieved.

Joe (Oliver Maltman), their lawyer son, is also seen at first as being emotionally unavailable. His parents have no idea of whether he has a girlfriend or not until he brings one — in the person of Katie (Karina Fernandez) home to meet them. But he and Katie end up appearing to have a chance at the sort of happiness Tom and Gerri, though no one else in the movie, appears to have. Like Joe’s parents, both of them are interested in other people and sympathetic towards their failures and misfortunes while at the same time maintaining a certain detachment, a cool self-possession that keeps them from being dragged down by the others. In the film’s fourth and final segment, some cause of estrangement has developed between Gerri and Mary. “You let me down,” says Gerry to her. Typically, we are not told what this is, but the fact that Gerri follows up by saying, “This is my family,” indicates that she means to draw a circle inclusive of Tom and Joe and Katie and even Ronnie, the other people present at the time, but not Mary. Perhaps Mary’s sexual suggestiveness to Joe is her way of trying to force her way into that circle, even if it is not what has led to the estrangement.

And yet Mary is forgiven, again, and in the final scene, Tom and Gerri and Joe and Katie and Mary and Ronnie are seated around the table at dinner as we listen to the film’s only serious excursion outside its own present. Tom is explaining how he and Mary met — on their first day at the university — and were separated by his first job in Australia; how she came out to Australia to meet him there and then how they traveled back to Britain together overland through Asia. Their sense of being plugged into the world outside their own is contrasted with the self-absorption of the others. Mary, for instance, talks of having worked as a barmaid in Corfu for a while, but this has produced no lingering result, no shared memory that she cares to contribute to the discussion. Even Katie, who once spent time in Sydney, is not shown as having brought anything back with her, though she claims to have enjoyed it.

Just before this dinner, and before we hear of her having alienated Tom and Gerri to some extent, Mary appears to have designs on the recently widowed Ronnie almost as soon as she meets him, unpromising material though he would seem to be for any relationship, and tries to make conversation. “It’s really lovely to have someone to talk to,” she says to the virtually catatonic Ronnie, echoing her own words to Gerri in the opening segment. Hearing a song playing on the radio, she asks him, “Did you like the Beatles?”

Ronnie answers with a typically laconic: “They were all right” — but then he adds, unexpectedly: “I was more Elvis. Jerry Lee Lewis.”

“‘All shook up,’” says Mary — which, in the context, is a great joke.

Mike Leigh used to be all shook up too but, perhaps because he has grown older, he is now less inclined to anatomize people’s griefs and grievances, instead focusing on that much rarer quality of contentment that we see in Tom and Gerri, whose names are an ironic allusion to the battling cat and mouse of cartoondom. This Tom and Gerri enjoy a kind of peaceful acceptance of the world as they find it which is at the opposite extreme to the revolutionary sentiments that have at times in the past bubbled to the surface in Mike Leigh’s movies. To my eye, Mr Leigh in his maturity (he turns 68 on Sunday) has finally managed to see past the class antagonisms with which he has at times in the past been almost obsessed, at times to the detriment of his movies, and instead trained his sharp eye on a human problem which transcends the vicarious resentments so beloved of those critics who prefer politics to humanity.

At one point, as Tom and Gerri are reading in bed together, he says to her: “I never liked history at school, but it seems more relevant as you get older.”

“We’ll be part of history soon,” says Gerri without emotion.

“Exactly,” says Tom.

Could happiness in the end be something as simple as remaining open and sympathetic to the emotional losses of others while declining to complain about one’s own? It may be so.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.