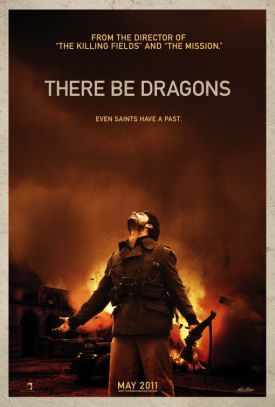

There Be Dragons

Some people will like There Be Dragons by Roland Joffe (The Killing Fields, The Mission) because it is something of a throwback to the Hollywood epics of old in which a (usually) tragic romance is set against the background of real world-historical events like wars and revolutions. The individuals’ experience of these events, as in Gone With the Wind or David Lean’s Dr Zhivago is supposed to cast dry historical narrative in a new and more thrillingly human light. As an example of this kind of movie, however, I think Mr Joffe’s film is less than completely successful. What I liked about it was that it was a different kind of throwback: to a time when Hollywood, if only out of its own self-interest in trying to attract an audience largely made up of Christian believers, had to be at least respectful to religion and sometimes produced movies that were themselves quasi-iconic aids to Christian devotion.

Xavier Beauvois’s Of Gods and Men is that kind of movie, but it owes little or nothing to Hollywood. Mr Joffe’s picture, by contrast, is Hollywood through and through, and that’s its weakness. Half of it is about St. Josemaría Escrivá (Charlie Cox), the founder of Opus Dei, but his story, set against the background of the Spanish Civil War, has to compete with that of a fictional rivalry with his childhood friend, Manolo (Wes Bentley). We learn of Manolo’s joining the Republican side as an agent of the fascists, of his unrequited passion for a Beautiful Hungarian Communist (Olga Kurylenko), of the BHC’s spurning him for love of the Communist leader, Oriol (Rodrigo Santoro), of Manolo’s crises of conscience with regard to (a) the BHC and his rival and (b) his ex-friend, the priest — and, as if all this weren’t enough, of the dying Manolo’s complicated relationship nearly 50 years later with his son, Robert (Dougray Scott), who happens to be writing a biography of Josemaría Escrivá and is only now discovering his father’s relationship with his subject.

This, the chronologically latest part of the story, is set in 1982 and serves as a framing device for the rest of the picture, as old Manolo’s memories of his early life and the Civil War, put on tape for his son the biographer, are the ostensible occasion of their realization on the screen. But of course the son also has to learn the hitherto unknown and shocking details of his own history and come to some kind of terms with his father before the latter dies — and that in such a way as to affirm the message and meaning of Father Escrivá’s ministry. It should be readily apparent that Mr Joffe is unwilling to allow what he regards as the less-interesting saint’s life to assume the center stage but must constantly be distracting us with either the romance or the family drama in such a way as to defeat his own purpose in trying to put the two stories together.

The movie’s tag line, taken from Oscar Wilde — “Every saint has a past, and every sinner has a future” — really has nothing to do with the stories it has to tell but, like the romance stuff, is there to make the viewers think they’re getting something more steamy than they really are. All that having been said, however, the movie does have some of the visual splendor of the old time epic and rather more of the saintliness of Father Escrivá than we could reasonably have expected. It does a good job of evoking the time and place of its setting and, almost as remarkable as its sympathy for the saint’s Christian piety, it avoids any glamorization of the Republicans — or, for that matter, of the Fascists. The murderous hatred towards the clergy of these storied and often-glamorized “anti-fascists,” both the communists and the anarchists, is well-documented but a story seldom if ever told in the movies before.

Indeed, I’d have thought there would be quite enough real-life excitement in an account of Father Escrivá’s hair’s-breadth escapes from the killer-commies and therefore no necessity to weigh it down with the rather clunky fictional romance, but here, too, Mr Joffe must have felt the danger of being seen inadvertently to glamorize the fascists if he had too freely portrayed the republicans as the bad guys that they so often were. The best parts of the film are those in which the priest is called upon to put his priestly duty to others ahead of his own safety, but it doesn’t do, I guess, to show too many of these. Likewise, his idea for Opus Dei — “Everyone and everything for your glory” — together with the Catholic establishment’s view that “It all sounds rather Protestant: that God is to be found in the vanities of daily life” — could have done with a lot more explication but was presumably thought too boring. Or else too politically risky. Still, what there is of a recognizable portrait of piety and holiness makes this a movie worth seeing.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.