Trash Collection

From The American SpectatorWhen I was a boy, my mother wouldn’t let me read comic books for an unusual reason. At least it’s not one that I have ever heard of another parent’s citing in favor of such a prohibition. It wasn’t because the comics were morally or intellectually corrupting, or because they would spoil my appetite for quality or “improving” sorts of literary experiences. It wasn’t because she had read Frederic Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent and believed — as David Hajdu’s Ten-Cent Plague recently claimed millions of moms did in the ‘50s and ‘60s — that comics were politically subversive. No, it was because, according to her, comix would ruin my ability to spell correctly. If readers have ever heard this charge made against them before, I would be grateful to hear from them. The odd thing was that, although I always was and still am a pretty good speller, I can’t remember ever seeing a misspelled word in any of the comic books that I used to sneak into the house under my shirt and hide under my bed. Maybe comic books when she was a girl, such as they were, were different.

Anyway, it seems in retrospect that I only liked to read them because they were forbidden. Their equivalents in pulp fiction never had the same charm for me, for instance, though both would equally have been considered “trash” by my mother. This was not because the latter didn’t have pictures — which, being partially color-blind, I couldn’t see properly anyway — but because (I assume) the pulps and science fiction were not forbidden me the way the comics were. Apart from my surreptitious truancies with Superman and his kind, I mostly read history books and a few favorite novels, mainly Huckleberry Finn, multiple times. I sometimes wonder if the whole charade of prohibition and secret defiance that went on between my mother and me wasn’t intended from the beginning to channel my subversive impulses into relatively harmless courses.

At least they seemed so at the time. Now, of course, as I have noticed before in these pages (see “In Defense of Snobbery” in The American Spectator of July-August, 2008) and never cease to marvel at in the movie reviews I write for the magazine’s website, the comics are the master art-form of our age. Heavy-duty think pieces in the Sunday New York Times — “All the News that’s Fit to Print” used to be its motto — are devoted to what no one but, ironically, me considers trash anymore. Nothing is trash anymore. Or everything is. It comes to the same thing. Axel Alonso, the new editor in chief of Marvel Comics (now a division of Disney), is solemnly quoted by the Times’s reporter as saying that “There’s no type of fiction that comes close to comics for the layers of storytelling. . . This is mythology, but it’s not mythology that’s refined slightly over time. It’s mythology that’s constantly evolving.” No, no! Mythologies are things we believe in — like the primal significance of youthful rebellion against authority — things which we re-enact again and again (see “Rebels Without a Clue” in The American Spectator of June, 2010) in order to reinforce our belief in them. Comics are the opposite: throwaway fantasies that we demand to be made ever new, and ever more unbelievable.

Unless we are delusional, that is, comic books are things that we love precisely because they are unbelievable — because they provide us with a holiday from realities we find unpleasant or frightening. Morven Crumlish may write in The Guardian that, as a girl, she loved Wonder Woman “because she seemed utterly feasible to me,” but I think she means the opposite of what she says. If Wonder Woman had been “feasible” — that is, do-able — for her, she wouldn’t have been sufficiently Wonderful to have taken up the space that she seems to have occupied in her girlish imagination. Ms Crumlish now gives herself retrospective credit for a sort of credulity that she is most unlikely to have had at the time in order to express in stronger terms her approval of the political symbolism underlying the fantasy of feminine superpowers. Like Mr Alonso she wants, now, to see the comic as myth: the re-enactable myth of female empowerment of which Wonder Woman’s superpowers were a metaphorical expression. But I think her childish self must have had a better grasp of the distinction between reality and wish-fulfilling fantasy than she apparently has now.

Moreover, the brightly-colored hyper-realism of the comics sends its own message about the necessarily fantastical nature of what they represent. The same paradox applies to 3-D, which couldn’t take hold in the movies to the extent that it now has until the movies themselves had become as completely identified with fantasy as the comics have always been. The closer you get to perfect visual verisimilitude, the further away you get from any other kind, since you are inevitably emphasizing the artifice of the medium by heightening the audience’s sense of illusion in experiencing it. That’s why the motto of the anti-3-D party in Hollywood is, according to Michael Cieply, also of The New York Times, “If you can’t make it good, make it 3-D.” There does seem to be a finite amount of disbelief-suspension that a movie-maker, like any other artist, can ask of his audience. If he uses it all up on spectacular visuals, there’s bound to be nothing left for anything else, and he ends up with — Avatar, which is both the highest-grossing movie of all times and one of the worst, in my view.

And there’s another paradox for you. Audiences seem to love this trash — perhaps just because, like comic books, it so obviously is detached from reality — and yet a lot of directors who have somehow managed to retain a shred of artistic integrity in spite of having worked in Hollywood for years don’t. They’re balking at the suits’ desire for more and more lucrative 3-D pictures. According to Mr Cieply, at the most recent Comic-Con convention in San Diego audiences applauded those film-makers who had resisted the studios’ pressure to make their movies in 3-D — or, even worse, to turn them into 3-D movies once they had been made in 2-D.

The crowds cheered, as they had in an earlier Comic-Con briefing by Chris Pirrotta and other staff members of the fan site TheOneRing.net, who assured 300 listeners that a pair of planned Hobbit films will not be in 3-D, based on the site’s extensive reporting. “Out of 450 people surveyed, 450 don’t want 3D for The Hobbit,” a later post on the Web site said. But in Hollywood, an executive briefed on the matter — who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the delicate negotiations surrounding a plan to have Peter Jackson direct the Hobbit films — said the dimensional status of the movie remained unresolved.

The dimensional status! There’s status anxiety for you. So on the one hand you have Hobbits stretching off into the distance as far as the eye can see, and on the other you have a visceral reaction among a lot of the people who have chosen to deal with this and similar stuff for a living against the movies’ further leap into the merely cartoonish and fantastical. Their willingness to pander to the most debased and unconservative of tastes appears to have its limit after all. Who knew?

|

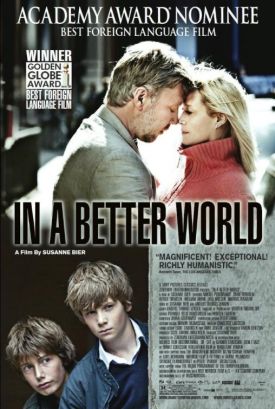

Could this be a sign of a growing movement in the direction of reality in the movie industry? It’s hardly shown up yet in the movies made in America, the homeland of unreality, but the fact that it has shown up at all could be taken as significant of a larger cultural shift. I am not the first to notice that of the films which were up for the Best Picture Award at the Oscars this year, all but two of the expanded category of ten were made for grown-ups. Four or five of them were even not too bad, though two of these (including the winner, The King’s Speech) were made by foreign directors. And by far the best in any category was (as ususal) the Best Foreign Language film, In a Better World by the marvelous Dane, Susanne Bier.

Yet on the bright side there was no Avatar in sight. Not that there won’t be plenty more Avatar wannabes, lots in 3-D, in the summer blockbuster season now just beginning. I doubt that there will be many parents today who will try to keep their children away from the trash, if only because pretty much everything is trash now. By forbidding it they might even succeed, as my mother did, in making the trash more attractive. On the other hand, in a different cultural context — a context where almost nothing is forbidden to them — children might instead begin to get the idea that there is good and bad in art, not just generic entertainment, and that there might be some value to them in discriminating between the good and the bad. There’s no way to know unless you try.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.