Monuments to Lost Meaning

From The American SpectatorAll culture begins with commemoration of the past and honor rendered to the dead. The oldest literary monuments in the Western tradition, the Iliad and the Odyssey seemed to their original audience to be historical accounts, in suitably decorative form, of events they believed should not be forgotten by those who would be born long after all who fought at Troy were dead. Probably, the cave paintings at Lascaux, six times older than the Trojan War, were meant to commemorate a particularly memorable hunt, a kind of memory of whose victims has outlived by seventeen millennia anyone’s memory of the hunters. Such irony — by which I mean the tendency of meaning to change with context — is routine. Shelley’s Ozymandias, whose “shatter’d visage” and “vast and trunkless legs of stone” were all that remained of those works upon which that hero had once invited the mighty to look and despair, is rather the rule than the exception for those in the commemorative trade, given a long-enough perspective.

All such commemorations are not only of events and the people who were involved in them but also of the meaning of those events in the eyes of the commemorators. They build their monuments not only in order that great deeds should not be forgotten but, ipso facto, to defend the greatness of the deeds and the men who performed them against the insolence and irreverence of time. Ultimately, of course, time proves to be pretty unbeatable, even by marble and the gilded monuments of princes — even by the rhymes that Shakespeare said would outlast them. But long before “the unswept stone” in his Sonnet 55 is “besmear’d with sluttish time,” the context of such perdurable goods changes and, with it, their meaning. Thus the Roman-style monuments to conquest and victory still to be seen in London or Paris have become only a century or so later rather an embarrassment for many of the British and French grand-children of those who built them, along with the national honor and the empires they were meant to commemorate.

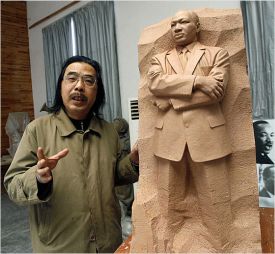

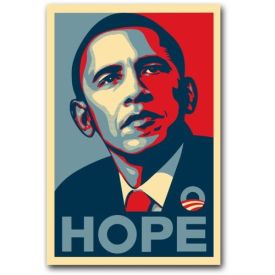

Indeed, as the newly unveiled monument to Martin Luther King on the Mall in our nation’s capital shows, the context can change its meaning before the monument is even built. Ostensibly there among the Founders and preservers of the Union for as long as the Union itself endures, the colossal image of Dr King in granite was presumably placed there to memorialize the new birth of civil rights for all races that he did so much to bring about less than half a century ago. Yet already it conveys quite a different meaning — and deliberately so. Done in socialist-realist style by a Chinese sculptor whose more usual subject has been the late communist dictator and mass murderer Mao Zedong, this image of America’s non-violent civil rights hero appears to have been designed to stand less for his genuine accomplishments than for his later “progressive” opinions, once thought to be un-American — for example, those related to the twin progressive fantasies of a superstate to guarantee the good things of life to all and a (rather contradictory?) world government to take the place of national sovereignty.

Although this incongruous portrayal of King as Dear Leader explicitly commemorates his genuine accomplishments, its style together with its placing of them in the context of his aspirational utopianism has the effect of making it into a monument to unreality — perhaps because so many of today’s heirs of the civil rights movement, like Rep. André Carson, have decided that their political interests lie in upholding the fantasy that King really changed nothing and that the Tea Party, for instance, represents a concerted attempt to return America to the days of lynchings and Jim Crow segregation. Indeed, to a certain kind of post-honor sensibility, the colossal King transforms the context of the much-commemorated achievements of the Founders nearby, rather than being transformed by it. Thus Philip Kennicott of the Washington Post, reviewing what he affects to regard as the “mostly harmless and neighborly” Chinese King statue, argues that “this newest addition to the national clutter will eventually fade into Washington’s marble background of benches, bollards and inspirational blather.”

So much for honor! I particularly savor the irony in the fact that one of the stone-masons imported along with the statue from the Middle Kingdom told Courtland Milloy of the Post that he and his colleagues were working on it not for pay (the King family, by the way, demanded and got some $800,000 for the use of their ancestor’s words and not very like likeness) but for the “national honor” — meaning China’s national honor. Here, by contrast, the massive slabs of granite at their very unveiling are rhetorically reduced with little fuss to “clutter” and “inspirational blather.” It’s hard to avoid the suspicion that what the statue was first intended to make us remember has already been forgotten — along with so much else that we used to think was an important, even an essential part of our national identity. The historical irony thus built into the statue is that, in honoring a great man, we now mean not to affirm but to deny the concept of greatness itself. King as the martyred visionary is presented to us not only as a monument to a distinctive kind of 20th century failure, like the many toppled and untoppled communist Big Men he so much resembles, but also as a rebuke to King the man of action and doer of great and unblatheringly inspirational deeds for believing in the goodness of America.

|

Irony of quite a different kind was present in many of the commemorations of the tenth anniversary of 9/11. I was particularly taken with the exhibition at the International Center of Photography in New York, the Centre de Cultura Contempor nia de Barcelona and the Imperial War Museum in London called Memory Remains by the Catalan photographer Francesc Torres. Without any context, Mr Torres’s series of photographs portray mere junk, albeit junk removed from those normal junky contexts of casualty, decay, failure, abandonment or random destruction, and placed as incongruously and ironically as Martin Luther King’s image on the mall in a JFK airport hangar. You could entertain yourself by regarding the images of these broken buildings and machines belonging to everyday life as abstract forms but only by deliberately forgetting that they were removed from the site of the ruined World Trade Center ten years ago and brought here so that people could remind themselves of that ruin.

In the book that accompanies the exhibition, Mr Torres writes that

over the last century we have developed in the retinal and conceptual arts a visual vocabulary that didn’t exist before modernism. We have grown accustomed to perceiving bent steel (Richard Serra) and crushed cars as sculpture (John Chamberlain), and charred and eroded surfaces as painting (Jasper Johns, Antoni Tapies, Anselm Kiefer). All these and more — discarded clothes, personal belongings, papers and documents — are now fully assimilated into the history and tradition of modern Western art, making very difficult a strict distinction between documentary and aesthetic qualities.

In other words, the context in this case does not just change the meaning, it is the meaning — as, indeed, it is for modernist and conceptual art. The power of time to diminish that meaning as the shock of September 11th, 2001 gradually wears off is as great as ever, but at least it is not so easy to transform it into something quite different by political chicanery. I think that this power to transcend politics — which, as Hurricane Irene so recently reminded us, is vouchsafed to fewer and fewer people and events in our national life — is a big part of what makes these images so evocative.

At any rate, it’s clear that national honor and pride, which once had that power, have it no more — which may be one reason why national catastrophe and defeat still does. It’s true that some may repair to Mr Torres’s photographs or the bizarre waterfall memorial at Ground Zero or other images or reminders of disaster in order to keep their hatred of the enemy burning bright while others, like the so-called “truthers,” will do so in order to keep their hatred of someone other than the enemy (are you listening George W. Bush and Dick Cheney?) burning bright. But most people who look at them, like most people taking part in the other tenth anniversary events and remembrances do so in a pure spirit of the response to tragedy as identified by Aristotle, that is in a spirit of pity and terror. More even than an aesthetically correct response, this is a Christian response, it seems to me, since the image at the heart of the Christian faith is of a man dying on a cross — which also commemorates a defeat and a tragedy. Don’t tell the ascendant forces of militant secularism, however. They really won’t like that.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.