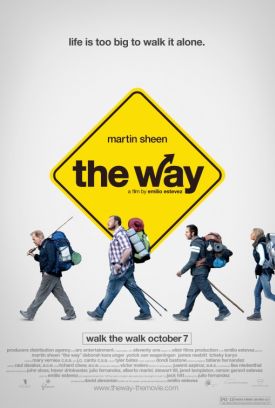

Way, The

In case you were worried, the New York Times review of Emilio Estevez’s The Way will reassure you that “This is not an ‘inspirational film’ in the usual, syrupy sense.” Phew! Dodged a bullet there, didn’t we? One can well imagine that the “syrupy” sort of inspirational film would be offensive to the sensibility that these days informs the arts pages as well as the other pages of The New York Times. But, then, the quotation marks around “inspirational film” seem to be meant to imply — I can’t think what else they are doing there — that there is no such thing as an inspirational film anyway: only the kind that strives to be inspirational and fails. Inspiring The New York Times, we may as well admit, is something probably better not even attempted.

Mr Estevez’s film, for which he also wrote the screenplay, is about a medieval pilgrimage — the one to Santiago de Compostela in Spain — which is still made by thousands of pilgrims today. Many, if not most, do so in a spirit of Catholic piety, but The Way is not interested in them. Fortunately, as the Times reviewer writes, “none of these people are [sic] overtly finding God on this trek.” How about covertly finding God? He doesn’t know, but I guess that that would be OK. “The beauty of the movie, in fact, is that Mr. Estevez does not make explicit what any of them find, beyond friendship. He lets these four fine actors convey that true personal transformations are not announced with fanfare, but happen internally.” So how do we know that they happen at all? Forget fanfares, where is the beauty in not knowing something?

The first of the four fine actors is Martin Sheen as Tom Avery, a California ophthalmologist whose son (Mr Sheen’s real life son, who is also the writer-director, Mr Estevez) has been killed by a storm on the first day of the pilgrimage. His purpose in making it had been obscure but, so far as we know, was only a part of a more general Wanderlust that made him drop out of graduate school, aged nearly 40. Being a globe-trotting bum subsequently becomes the ideal Tom aspires to when, after arriving at the beginning of the camino in Saint-Jean-de-Luz in France to collect the body, he decides on impulse to do the pilgrimage himself. He claims his son’s gear — including a backpack with, for some unexplained reason, the flag of the Japanese Navy on it — has the body cremated and then walks the 500 miles to Compostela carrying his ashes.

Along the way he meets Joost (Yorick van Wageningen), a fat Dutchman trying to lose weight, Sarah (Deborah Kara Unger) a bad-tempered and stand-offish Canadian trying to give up smoking and Jack (James Nesbitt) a loquacious Irishman (in the movies, of course, there is no other kind) with writer’s block. The four of them walk and have adventures together for most of the journey, all of which would look like a lot of fun, but for the fact that all four of them have secret sorrows which they have not divulged to anyone and which are meant retrospectively to explain the reasons for their pilgrimage. For, inevitably, the secrets emerge in the course of the journey, along with conflict and cameraderie, a common taste for the unpilgrimlike comforts of home and for gypsy merry-making.

Tom’s secret sorrow, of course, we know already. It’s that his son has died and he is carrying his ashes to Compostela — and, as it turns out, beyond. But for some reason Tom doesn’t want anyone else to know this. Making it a secret at least produces a certain symmetry with the other pilgrims, however, each of whom has a damaged soul and so must be in need of some kind of spiritual healing. To that end, as you might be pardoned for supposing, there is a whacking great church at the end of their journey in which we see bits of what might be a rather moving service of some kind taking place. Especially memorable is the part where a massive thurible or incense-burner called in Galician a botefumeiro, suspended from the cathedral dome by a pulley, is swung on heavy ropes up to the ceiling of the north transept and down to that of the south from their central crossing by eight priests in red robes. This really happens in the cathedral at Compostela.

Yet even though we see one of the pilgrims there with teary eyes, the film offers no other indication that anything spiritual, let alone any healing, is going on in it. Never mind. As David Carr, another writer for the New York Times, puts it, “Each member of the ad hoc tribe finds something he or she needs along the way.” See if you can guess what it is. I’ll give you a hint. Mr Estevez goes out of his way to suggest that, whatever two of them have found, it is not what they set out to find. Sarah does not quit smoking, Joost doesn’t slim down. The former insists she was never really intending to quit, the latter that he needed some new clothes anyway. Bingo! Obviously, what they have found is a New Agey contentment with who and what they are. “I think the movie reminds us that we each have to embrace our brokenness,” Mr. Sheen told Mr Carr. “We live at a time when we are supposedly supremely connected by technology, but I don’t see it. This is a film about very different people walking together who find a way to connect with each other.”

Oh, so that’s what they needed. But why the pilgrimage, then, rather than a TV reality show — or a bowling team, for that matter? All congratulations to Mr Estevez for treating religion, insofar as there is any in his movie, with a sort of distant respect. The Irishman does briefly allude to recent scandals in Ireland, where churches became “temples of tears,” as the reason why (he says) he doesn’t go in them anymore, but what we actually see of Catholic belief and believers, although not offering anything either we or the characters “need,” does not reflect negatively on them either. What religion offers to most people — and, I would guess, to most pilgrims — makes no appearance here. Like those inward “transformations,” if any, it is invisible. But whatever it may be, I feel safe in saying that it is not a feel-good, Oprah-like therapeutic dose of self-esteem but something altogether different.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.