Sex, lies and Amanda Knox

From The New CriterionSome of our neighbors had their Hallowe’en decorations up early this year. Now that what used to be called Decoration Day has become “Memorial Day weekend” and Easter is hardly observed at all, Halloween is the new hot holiday, rivaling Christmas as the occasion for decorations. Among those on the front lawn belonging to one of the neighbors this year was a sign reading: “You say witch [the word written in scary, shivery italics] like it’s a bad thing.” The joke, I suppose, is that hardly anyone ever does say “witch” like it’s a bad thing anymore. And if anyone does, he — it always seems to be a he — becomes the joke.

So Carlo Pacelli discovered when he called the Seattle co-ed Amanda Knox an “enchanting witch” at her retrial in Perugia on a charge of having murdered her British room-mate, Meredith Kercher. Mr Pacelli was the lawyer for the man, Diya “Patrick” Lumumba, whom Miss Knox had first and falsely accused of the crime. This time, the court bought her story that she had only identified him as the culprit under duress after an all-night police interrogation. It also bought her story that she and her Italian boyfriend, Raffaele Sollecito, were innocent of the murder, though they had served four years of a 26-year sentence for it.

For a brief moment, however, Mr Pacelli made himself into the major wrong-doer in the affair by having brought up the subject of witches in connection with it. Feminists across the post-Christian world took up their keyboards as a single feminist to denounce him. “Amanda Knox is a witch?” headlined The Guardian “Sorry, are we living in 1486?” To the unofficial jury of the media, at any rate, it seemed the clincher of her innocence. Suddenly she was being tried not for murder but for being a witch — and for the same reason that, so feminist orthodoxy holds, the witches of old were: that is, for daring to express female sexual desire. Miss Knox was generally acknowledged to have had, as one of her media admirers demurely put it, a “vigorous sexual appetite,” and the original prosecution narrative of what happened that night in 2007 was some kind of drug-fueled “sex game gone wrong” involving herself, Mr Sollecito, Miss Kercher and the man still in prison for her murder, Rudy Guede. If you weren’t buying that anymore, and suddenly no one was, what you were watching was the “Amanda Knox witch trial, live on your television.”

But hang on a minute. Like Mr Pacelli, I’m saying “witch” like it’s a bad thing. “Who is Amanda Knox?” he had asked. “Is she the mild, sweet young woman with no makeup you see before you today? Or is she, in fact, the one I have described and who emerges from the court papers on the basis of eyewitness portraits, given over to lust, narcotic substances and the consumption of alcohol?” Wait. Which was the good one and which was the bad one again? Maybe he himself hadn’t been quite so sure as he had sounded before when he answered his own question by deciding that she was both — “the one and the other. In her, there is a double soul: the good, angelic, compassionate one … tender and ingenuous, and the Lucifer-like, demonic, satanic, diabolic one that at times wanted to live out borderline, extreme actions and dissolute behavior.” Well, when you put it like that, it does sound kind of like a bad thing.

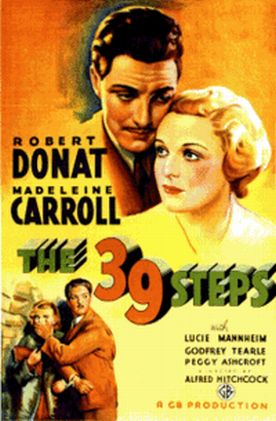

Last year Anthony Daniels, under his pen name of Theodore Dalrymple, wrote for The Wall Street Journal a characteristically thoughtful piece on the fiftieth anniversary of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho which he saw in relation to Norman Mailer’s nearly contemporaneous essay, “The White Negro” and its celebration of the hipster as psychopath. As he paraphrased Mailer: “Freeing the inner psychopath — that is to say, the natural, impulsive person without the accretions of convention to detain him — will paradoxically make for better, as well as more authentic, conduct.” But then he added (apologies for the spoiler):

The film also served, intentionally or not, to promote what might be called the “psychology of the real me,” according to which bad deeds can be repudiated as not being those of the true (and invariably good) essence of the person. Norman Bates is revealed at the end of the film to be inhabited by two people, his real self and his mother’s self; and it is his mother’s self within him who commits the murders, as she is jealous of the potential relationship between Norman and the murdered heroine. That is why Norman Bates dons a wig and a dress when he kills.

After relating some examples of his own criminal psychiatric patients who had managed to distance themselves from their actions by denying that they could have been the product of “the real me,” Dr Daniels went on to point out that

the psychology of the real me is surprisingly similar to belief in possession by evil spirits. An alien force colonizes an otherwise sane and sound mind, forcing the possessed person to behave in a wicked way. By strange coincidence, the wickedness perpetrated by the alien force conforms to the secret wishes or interests of the person possessed by it — but who, without the possession, would never dare to carry it out. The wickedness is repeated until successful exorcism, either by a priest, a psychoanalyst or a psychiatrist, is carried out. Psycho, then, is a medieval tale in modern costume. The Enlightenment never reached the Bates Motel.

I sense a contradiction here. He says that “the real me” in the case of Norman Bates was the decent, well-mannered young motel proprietor, whereas Norman Mailer’s “real me” is the psychopath who has broken free of social constraints to gratify its lust for blood — and thereafter, presumably, to upbraid anyone who continued to speak of psychopaths as if they were a bad thing.

Yet I also think that the contradiction may be more apparent than real. The point of the doctrine of “the real me” is the convenience it offers us of being able to choose which of the many possible mes within each of us we want to garland with the epithet real. For the doctor’s criminal patients it tended to be, for understandable reasons, the me that does not maim or murder other people; for a romantic, would-be “existentialist” like Norman Mailer, it was fun at least toying with the idea of its being the me that does.

The same ambiguity must have been at work in the media’s fascination with Amanda Knox. “So who is the real Amanda Knox?” asked the headline in The Daily Telegraph on the news of her acquittal — alluding not to Mr Pacelli’s dichotomy but to that of the Italian judge, Claudio Pratillo Hellmann, who was quoted as saying that her acquittal was only a result of “the truth that was created in the trial” while “the real truth could be different. They [she and Mr Sollecito] could also be responsible, but the proof wasn’t there.” During the trial another lawyer, this time female and acting for Mr Sollecito, had bizarrely compared Miss Knox to the cartoon seductress Jessica Rabbit (from the movie Who Framed Roger Rabbit) and her punning apologia, “I’m not bad, I’m just drawn that way.” Here was another seeming confirmation of the feminist complaint that female sexuality is routinely forced by the patriarchy to conform to the Madonna-whore model. As Bryony Gordon of the Telegraph put it, “she liked sex, so she must be a killer.”

Doubtless there is something in that, but Miss Gordon’s own fascination with the case, like that of the rest of the media, suggests that there is more to it — a suspicion, perhaps, that she liked sex, so she might be a killer. What titillates about the case, in other words, is not just the sex and violence but the continuing uncertainty about just how they are linked. It’s the same ambiguity suggested by Dr Daniels in relation to Psycho, which made and still makes the impression it does on audiences not because of its dubious psychoanalysis but precisely because we don’t know anymore whether the nice young man or his crazy old mother is the real Norman Bates. The real appeal of “the real me” is the indeterminate extent to which it is unreal. Reality itself melts away, leaving us with the sense of uncertainty and danger that Burke identified with the Sublime. The nature that proclaims its might before our smallness turns out to be human nature.

Those of us who are interested in the Amanda Knox case are so just because we don’t know for sure whether she is guilty or innocent. Like Mr Pacelli, perhaps, at least some may suspect that Miss Knox is a witch, or as good as one. At any rate, the sense of ambiguity about “the real Amanda Knox” is at least part of what now promises to make her a millionairess many times over. As I write, those engaged in the bidding war for her first television interview are said to be expecting to pay $10 million for it, with nearly as much likely to come her way in the form of some lucky publisher’s advance for her memoirs, already begun in jail.

For Miss Knox, also known to the press as Foxy Knoxy, the subtext was that of Norman Bates or those who told Theodore Dalrymple that the real them had been somewhere else when criminal deeds were done. Although she claimed not to know how poor Miss Kercher met her grisly end — she bled to death from a knife wound to the neck — it still seemed, if not as likely as at her first trial still not unlikely, that she was implicated in it somehow. Or perhaps it was just her evil genius, that not-me as familiar as was Charles Manson to the poet Thom Gunn in his “Jack Straw’s Castle.”

Some such feeling as Gunn’s — that is an inability entirely to separate oneself from an object of horrible fascination — was hinted at by Jennifer Lipman in the Daily Telegraph for whom Miss Knox’s belated deliverance from imprisonment and shame looked like her own fate fortuitously avoided.

If you were to look through my Facebook photographs, from over the last five years, you would see two versions of me. On the one hand, there I am as a dedicated student at two different graduation ceremonies, a bridesmaid, a keen baker, someone who came perilously close to tigers in Thailand and caught piranhas in Brazil. Then there I am at clubs and bars, in not particularly modest outfits and with a drink in my hand. There I am making cocktails in a messy student house, on a hen night, or with a disparate collection of male and female friends. In reality, there’s nothing in my visual history that is particularly controversial and very little that you wouldn’t see in the photo albums of my friends. But if the unthinkable happened and I was thrust into the public eye, it would be very easy to paint my back-story using either the former or the latter. If the media vultures so chose, I could be the freshfaced innocent or her polar opposite. . . We may never know what circumstances led to Kercher’s death. But how different would the case have been had Knox been portrayed as the angel, and Kercher’s private life been subjected to the same forensic examination as that of her supposedly demonic flatmate?

She goes on to write that “Either way, the endless obsession with her looks, her sexual history and her “scandalous” behaviour belongs to the era of Victorian prurience, when women were either saint or sinner and there was no room for shades of grey.” But this is false profundity and another attempt to appropriate history for one’s own purposes. Victorian prurience, surely, was no match for the prurience of today. This is how people look at promiscuous or unauthorized sex and it is always how they have looked at it. Disguised in this analysis is a utopian assumption about some ideal world where no one will be interested in what sexually adventurous young women get up to — and frustration and anger that the real world keeps showing up the fantasy as a fantasy.

Also, of course, there is the element of “look-at-me.” I’ve done the same stuff as Foxy Knoxy, so I should be a celebrity as well.

Like most of their peers (myself included), they were students who were in the habit of doing things that, when cast in the wrong light, would not reflect well on them; things they might regret. Knox, in particular, apparently partied hard, drank, did drugs, had sex. Not necessarily the perfect role model for young girls, but likewise not the deviant she came to be seen as. Meredith’s sister, Stephanie, said yesterday that the victim had been forgotten in the drama of the case. She wasn’t wrong. What’s also been forgotten is that — at least in modern Britain, Italy and America — we no longer live in a time when “character” and “questionable morals” are unequivocal signs of guilt. At least, I thought that was the case.

I love those scare-quotes around “character” and “questionable morals.” More Victorian prurience, no doubt! But isn’t there also at least a hint in all this of Norman Mailer’s existential love affair with his wild, psychopathic self? The Lipman narrative — Amanda as me — was also taken up in The Independent by Christina Patterson who wrote that “We prefer a crazy story to the truth: None of us knows how we would behave if we were 20, and terrified, and in a foreign country, and in shock.” Who is this “we” of whom she speaks if not the media? Why did these terrible things happen? she asks:

Perhaps it was just because once there’s a story, even if it’s a crazy story, and even if it’s not all that clear where it came from, and even if the evidence for it is very, very slender, that story seems to harden into something that feels like truth. And so it’s important that that story doesn’t change, because if something that feels like a kind of truth can change, then anything can change, and we all need some things in the world that don’t.

Sounds to me like the media’s modus operandi, though the guilty party she has in mind is the Italian prosecutor, Giuliano Mignini. At the least it must be admitted that our continued fascination with the story of Foxy Knoxy very heavily depends on the fact that we’re still not quite sure the crazy story isn’t true — and that for many, and in spite of their sympathy for poor Miss Kercher, there must be a certain delight in thinking it might be.

Certainly the media and Miss Knox would both be considerably the poorer if it were still the case that, as the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.” It’s not. Now everyone is entitled to his own facts, and the doctrine of “the real me” has done much to reconcile us as a culture to what Stephen Colbert has called “truthiness.”

Truthiness is “What I say is right, and [nothing] anyone else says could possibly be true.” It’s not only that I feel it to be true, but that I feel it to be true. There’s not only an emotional quality, but there’s a selfish quality.

The semi-facetious doctrine of “truthiness” was developed as part of the left’s assault on President George W. Bush and his rhetorically often less-than-compelling justifications for the Iraq war. But by implication it was an assertion of the same right to self-defined truth on the left’s own behalf. Thus it became established media truth that President Bush’s alleged “truthiness” had amounted to “lies” even though there was never any evidence that he had not believed everything that he said about the Iraqi Weapons of Mass Destruction at the time he said it. His own truthiness (if that’s what it was) created an equal and opposite version of itself in the scandal-besotted media, much of which were prepared to follow the lead of the left in feeling it to be true that the President was a liar. There’s a certain irony in that, you must admit.

This tacit acceptance by the media of self-defined truth is what must lie behind a lot of current political rhetoric too. As President Obama traveled the country promoting his latest Keynesian stimulus bill — the truth of which characterization having been suitably obscured so far as most of the media were concerned by his description of it as a “jobs bill” — the appeal was based again and again on his conception (so he said) of “who we are” as a nation. The real us, like the real me, was being summoned to give evidence against some false Dmitri of a nation, some mythical paradise of small government and free markets that had been surreptitiously put forward by the Republicans and other malcontents in its place. Not surprisingly, the real us turned out to be a great deal more compliant with President Obama’s measures than the us that showed up through more conventional political lenses.

Meanwhile in New York and across the country gangs of truthily empowered demonstrators were identifying Wall Street — or banks or corporations or “the machine” or rich people or inequality or (at least in the case of one demonstrator who had been offered the privilege of a media microphone) the Jews — as the source of all their economic woes. “It doesn’t matter what you’re protesting. Just protest,” another demonstrator told The New York Times, and the form rather than the content of the protests was enough for them to be hailed by many on the left as their own version of the grass-roots Tea Party. They would not have been there, or not been cried up in the media for being there, which comes to the same thing, without the new entitlement to their own version of the facts. Perhaps people feel we owe it to them when there is manifestly so little else that they can call their own.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.