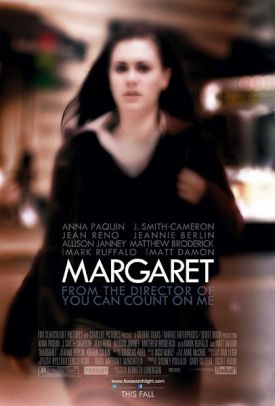

Margaret

“Spring and Fall” by Gerard Manley Hopkins — which begins (accent marks signifying Hopkins’s artificial or “sprung” rhythm)

Márgarét, áre you gríeving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

—

is probably his most famous poem and the one that, if you know anything about Hopkins, you must have heard and admired. But for all its admirable qualities, it sounds rather cynical and solipsistic. Musically it definitely has something to be said for it, but the conclusion in particular seems a bit too neat. Death, change, transition, the passage of time, all these are the “It” which, the poem tells us, are “the blight man was born for,” but if Margaret is cast into melancholy reflection or even grief by these things, then to go on to say as the poem’s last line does that “It is Margaret you mourn for” suggests the girl is, as we all are, trapped in the prison of self. Surely, it’s not just Margaret she mourns for?

For most people, in fact, it is not even primarily themselves they mourn for. When we lose something or someone we love and mourn the loss, it is the thing or person lost which is the object of our mourning, if you want to call it that. We mourn for ourselves only in the banal sense that we are the ones who have suffered the loss. That’s not at all the same thing as saying we’re mourning for ourselves. But then Margaret may have been, as Kenneth Lonergan’s movie Margaret hints she was, not like most people, or most mature people anyway. Her youth implies to him that youthful quality of self-dramatization to be found in those like his film’s heroine — named Lisa (Anna Paquin), not Margaret — who have not yet learned to find the borders between themselves and their experiences.

Lisa’s central experience is not exactly what you’d call mourning, because the person lost, an older woman named Monica (Allison Janney), was unknown to her until the moment of her death under the wheels of a bus whose driver (Mark Ruffalo) Lisa had distracted with a girlish question about a hat. Vaguely troubled by guilt and not wishing to get the driver in trouble, she lies to the police in her initial testimony (“Think of it like a movie,” the cop instructs her) and says that the red light we know the driver ran while being distracted was green. Later she has pangs of conscience about her lie and determines, by changing her story, to get the driver fired. Her struggle to this end — with the police, the legal system, Monica’s distant cousin in Arizona who is her next of kin and the feisty friend and executor Emily (Jeannie Berlin) who has no interest in being Lisa’s second mother — takes place in the context of the usual allowance of troubles, growing pains and everyday traumas of a clever and attractive high school senior.

Though it was released last September, Margaret has only recently made it to a cinema near me. The delay is just the latest of the misfortunes suffered by this picture, which was shot seven years ago and then ran into production and legal difficulties such that Variety has called it a film maudit. The critical raves which greeted Mr Lonergan’s directorial debut, You Can Count On Me (2000) may have tempted him into the over-ambitiousness that is evident throughout the film’s much-too-long 150 minutes. For although its subject is basically an ordinary kid, if an attractive, intelligent and privileged one, learning the ordinary lessons of maturity, albeit in unusual circumstances, Mr Lonergan seems to have been wrestling from the beginning with what he thought of as an epic, a portrait of American urban culture and society in the first decade of the 21st century. Consequently, the movie is like its heroine in trying to do too much. It piles on more weight of incident, character and meaning than its slender theme will bear.

At one point Emily says to Lisa, “This isn’t an opera! And we are not all supporting characters to the drama of your amazing life.” For a moment or two this seems to promise some way through the chaos, a way to relate Lisa’s adolescent self-dramatization to the rather operatic motifs — including opera itself — that the ambitious Mr Lonergan has added to it, but it is a promise that is never quite fulfilled. The moral maze that Lisa must negotiate has far too many twists and turns, and it eventually becomes as fatiguing to us as it evidently is to her. She is not a very likable character herself, at least until the end, and there are so many other centers of interest in the film only tangentially related to her and her struggles that our attention is constantly being distracted.

These distractions include her relationship with her actress mother Joan (J. Smith-Cameron) and Joan’s relationship with her new boyfriend, an opera-loving Colombian diplomat named Ramon (Jean Reno). In addition, there are ambiguous relations between Lisa and two different male classmates and another two of her teachers, played by Matthew Broderick (the Hopkins quoter) and Matt Damon, at the expensive Manhattan private school she attends, not to mention those with the bus driver and her distant father (played by Mr Lonergan himself) now remarried and living on the West Coast. All of this, together with the personal injury lawsuit against the bus company that Lisa, Emily and the Arizonan cousin all see in such different lights, is meant to take place against the backdrop of terrorism and America’s response to it in the wake of 9/11, which inspires a raging discussion involving Lisa and others in one of her classes

You will, perhaps, see what I mean about the film’s trying to do too much. Any one of these things could make an interesting subject for a film in itself but, taken all together, they produce an aesthetically and emotionally wearying effect. Yet in spite of its excesses and the structural problems they create, anyone with the patience to sit through Margaret will be rewarded with much that is worth watching, so talented is the director and his splendid cast. In some ways, even the chaos and indiscipline have their own contributions to make to the film’s portrait of moral confusion and rootlessness. That may be why the emotional power of its closing scene, set to the barcarolle “Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour” from Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann as sung by Renée Fleming and Susan Graham is so great. It reminds us that drama, and even melodrama, still have their uses, so long as we do not make Margaret’s (and Lisa’s) mistake and think that they’re all about us.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.