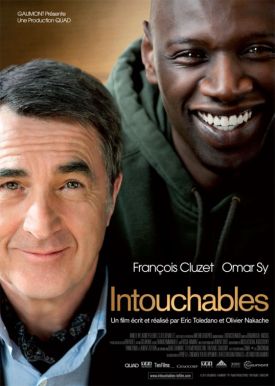

Intouchables,The

The Intouchables — a French film with a not-quite-English title — by the team of Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano (Those Happy Days) turns out to be a rather good illustration of the gulf between critical opinion and popular taste. Both A.O. Scott of The New York Times and David Denby of The New Yorker call the movie “an embarrassment,” while Jay Weissberg of Variety goes even further and calls it “offensive.” Et pourquoi? Because of the dreaded “stereotype” of a happy, vital, life-loving but criminal black servant and the impotent, stiff and hidebound white master who must learn from his supposed inferior how to live. This amounts, in the words of Mr Weissberg to “the kind of Uncle Tom racism one hopes has permanently exited American screens.”

Gosh! I guess there’s at least one way in which we can consider ourselves as being more enlightened than the French. But the idea seems to me an entirely silly one. Call the movie’s set-up a cliché if you like, but Uncle Tom racism? What does that even mean? Is any black man who takes a job working for a rich white guy automatically an Uncle Tom and therefore complicit in an oppressive system analogous to slavery? Or is anyone who creates a character in any way similar to a racial stereotype himself a racist, ipso facto? Clearly, most people don’t think so, unless you suppose (as some people like to do) that most people are racist. The Intouchables was enormously popular in France, and, for a foreign-language film only showing on a few screens, it is also very popular in here in the US. It’s almost as if ordinary people don’t care if the characters are stereotypes.

Of course, speaking as a critic myself, I should stick up for the honor of the profession and the right of the critic to tell people — as F.R. Leavis is supposed to have told his barber on the latter’s incautious confession to a liking for the novels of Arnold Bennett — that they only think they like the rubbish they claim to have a taste for. But I can’t help thinking that sometimes the popular taste can be truer than the more cultivated kind, especially where the latter is cultivated primarily by political correctness. Mr Scott, for example, can’t help sort of liking the movie in spite of himself, which ought to be a giveaway that he feels constrained to defer, as so many of us do, to the racial grievance industry.

Part of the reason for the film’s popularity is the attractiveness of its two central characters. Omar Sy plays the Senegalese Driss, a petty criminal and welfare chisler with a complicated home-life, while François Cluzet plays the rich-guy, Philippe, who has been paralyzed from the neck down in a paragliding accident and who needs more or less constant attendance. When one of Philippe’s rich friends warns him against the sudden caprice by which he decides to hire Driss — who has only applied for the job because of the demands of the welfare bureaucracy that he prove he is looking for work — in spite of his manifest unsuitability for this or pretty much any other job, he says “These street guys have no pity.”

“That’s what I want,” replies Philippe. “No pity.”

It’s a little too neat, like everything else about the picture. But that doesn’t make it worthless. The opening scene shows us Driss driving Philippe in the latter’s Maserati. But we don’t know this yet. Out of context, we can’t tell what to make of this young black guy and a complaisant older white guy (it’s not immediately clear that he is paralyzed), trying to outrun the cops, the former betting the latter 100 Euros that he can lose them and then, when he is caught, betting another 200 Euros that he can get them to give him an escort instead of arresting him — which he proceeds to do by persuading them that his white companion is suffering from a life-threatening emergency. The white guy goes along with the imposture by pretending to have some kind of fit.

Like naughty children, the two rejoice at their success in hoodwinking the authority figures and so suggest a typically French sense of the romance of criminal behavior. Later, the two of them smoke some dope together and concoct a clever fraud exploiting the credulity and sensationalism of the art market, but in a way that popular philistinism will find particularly congenial. If there is a cliché here it is more Rousseau (or even Cocteau) than Harriet Beecher Stowe. Moreover, if Philippe has to learn to loosen up from Driss, Driss has to learn from Philippe some of the habits of good citizenship and diligence in filling a place in the productive economy instead of seeking to live off welfare benefits. This makes for a more interesting and entertaining scenario than the merely clichéd one, but I suspect that it is also what, more than any putative racism, really gets up the nose of the politically correct.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.