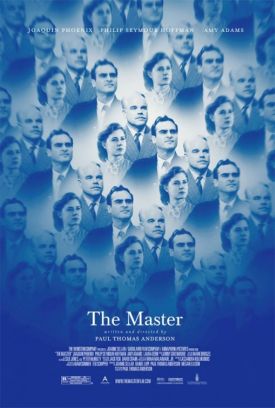

Master, The

Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master is an easy movie to like, or so I found it anyway. It stands in the great tradition of the American picaresque, going back at least to Huckleberry Finn, but with an Elmer Gantry cast. And, like Elmer Gantry, its larger-than-life hero is presented as a self-aware con-man. This is one Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), said to be loosely based on the real-life L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology. The movie is also set in what were Scientology’s early years, the 1950s, and the period — as the original season of Mad Men showed — could have made a statement all its own. Mr Anderson chooses not to use it in this way, to create a pointed historical contrast with the present, although he might have done so. In fact, he has surprisingly little to say about the America either of the 1950s or of today. Dodd is presented as sui generis and not obviously a creature of the land where religious entrepreneurs and patent psychotherapies have so often come to thrive.

Moreover, although his portrait of Dodd is a brilliant one, Mr Anderson is really more interested in one of his dupes. This is Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), a no-longer able seaman mustered out of the U.S. Navy at the end of the Second World War with some kind of unspecified post-traumatic stress. More likely, Freddie’s only real affliction is being Freddie — which involves an overly powerful appetite for sex and strong liquor. Mr Phoenix plays Freddie with a Popeye-the-sailor grimace and snarl that must be a deliberate allusion to that pop-cultural hero of yesteryear. But this is a Popeye stripped of his sometime uxoriousness and with a taste for home-made hooch instead of spinach. His skill, learned in the navy, at mixing up heavy-duty spirits out of paint thinner and developing fluid is what brings him to the attention of Mr Hoffman’s “Master,” though it is not necessarily what sustains him there.

As someone with a predisposition to see things in historical terms, I regret that The Master doesn’t have more to say about America’s past, but I think it does reflect an interest in America’s view of the past — which, paradoxically, may itself transcend to some extent the vicissitudes of history. Like the late Ron (Have You Lived Before This Life?) Hubbard, Lancaster Dodd is fascinated by the idea of reincarnation and makes it the centerpiece of his so-called church’s commercial appeal. When accused at one point of practicing hypnosis on his followers, he replies that, on the contrary, they come to him hypnotized and he wakes them up — that is, he claims to enable them to recall the past lives which the self-protective drowsiness of ordinary life has hidden from them, and to soothe and correct there the psychic traumas troubling their present lives that only his methods can detect.

That people are as ready as they are to believe anything so preposterous may have something to do with a peculiarly American form of historical anxiety which can only come to terms with the past by inserting ourselves into it, in one way or another, and to refashion the strangeness of our ancestors by remaking them in our own image. Dodd’s promises to those seeking to extend their historical memories by psychological manipulation are extraordinarily crude. At their last meeting, he tells Freddie that, in their previous life together, the two of them ran the pigeon post of Paris during the Franco-Prussian war. By this time, however, Freddie is able to regard such a bizarre claim with a fitting skepticism. Dodd’s way is so transparently fake and designed from commercial motives to appeal to his followers’ narcissism that even a lunk-head like Freddie must eventually see through it

|

Yet it is also clear that in his lapse from belief he has lost something real. The relationship between the two men, for so long as it lasts, enlarges and redeems both of them to some extent and constitutes the main substantive interest of the movie — together with the relationship of both to Peggy (Amy Adams), Dodd’s young wife. The latest Mrs Dodd may be the cult’s only true believer, not excepting its founder, and so drains off some of the pooling moral opprobrium that would otherwise be due to him. Unfortunately, this interesting triangle is immured in Mr Anderson’s brilliantly idiosyncratic cinematic technique and the gorgeous imagery of his director of photography, Mihai Malaimare Jr. It has nowhere to go. The story, such as it is, is told episodically and through a series of visually striking images with very little to connect them to each other. It is easy enough to follow but hardly necessary to do so, since the narrative arc is so shallow. Mostly what one takes away from The Master is its imagery, especially those images which are given a special significance and stand outside their temporal context.

The most significant of these is that of the sand woman which Freddie and his fellow sailors in the end-of-war passage at the beginning of the film sculpt on a deserted beach and to which they take turns making indecent suggestions that are half mockingly facetious and half aching with longing. Freddie’s lying alone in this mute giantess’s embrace comes to stand not only for his sexual unfulfilment but also for the need to worship an idol, later to express itself in his relationship with Dodd. When the two part ways, the latter, in a rare moment of self-revelation, bids a fond farewell to Freddie by enjoining: “If you figure a way to live without serving a master, any master, then let the rest of us know.” For a moment, at least, it is impossible not to feel some sympathy for this crooked, would-be “master” who at heart is as bereft as his deluded disciples.

Paul Thomas Anderson seems to me to approach not just the credulity of the Doddites but religious belief itself rather in the spirit of Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Oxen,” which ends with the wistful line, “Hoping it might be so.” The emotional power of the line lies partly in the fact that the hope is not directed at anything so momentous as the truth of the Christian revelation but at an obscure folk legend about kneeling cattle on Christmas eve. Nothing of importance would be proven one way or the other by the beasts’ kneeling or not kneeling, yet the poet’s hope would be satisfied by any acknowledgment of its Master on the part of the universe, even one so humble as a kneeling animal. In the same way, Mr Anderson teases us with a share in Freddie’s desperate hope that even a flim-flam man like Dodd, the humblest of God’s rational creatures, could be touched by grace. Neither he nor Freddie nor Dodd himself can quite see it in the end, but the hope remains.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.