The State of Our Nature

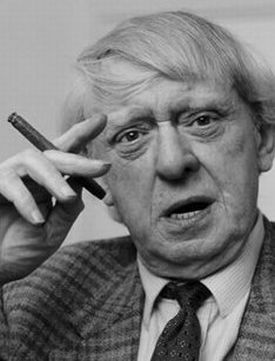

From The American SpectatorAnthony Burgess

Writing in The New York Times Book Review on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, Martin Amis notes that Burgess gave his novel different endings in different editions. In “the ‘dark’ ending” — the quotation marks sketching their author’s unmistakable sneer — the Beethoven-loving rapist and thug, Alex, pronounces himself “cured” of his violent tendencies but with a bitter irony suggesting that “his soul, such as it was, has been excised” by the tyrannical state’s resort to Pavlovian brainwashing. By contrast, in the “official version,” Alex merely “outgrows” his evil, claiming to aspire at age 18 to the bourgeois contentments of marriage and family. “It feels like a startling loss of nerve on Burgess’s part,” writes Mr Amis, “or a recrudescence (we recall that he was an Augustinian Catholic) of self-punitive guilt. Horrified by its own transgressive energy, the novel submits to a Reclamation Treatment sternly supplied by its author. Burgess knew something was wrong: ‘a work too didactic to be artistic,’ he half-conceded, ‘pure art dragged into the arena of morality.’”

Both novelists say that like it’s a bad thing — as if the great tradition of moralists in English fiction stretching back to Defoe and Richardson was a self-evidently dead letter. Mr Amis thinks Burgess “shouldn’t have worried: Alex may be a teenager, but readers are grown-ups, and are perfectly at peace with the unregenerate. Besides, A Clockwork Orange is in essence a black comedy. Confronted by evil, comedy feels no need to punish or correct. It answers with corrosive laughter.” That is certainly true of the laughter inspired by the antisocial antics of the eponymous hero of his own most recent novel, Lionel Asbo, another very young man who could have taken Alex’s correspondence course in thuggery. Neither Lionel’s creator nor anyone else we meet in the novel feels any need to punish or correct him, though he is constantly in and out of prison, where he feels content and at home. So far from being re-programmed by a sinister and tyrannical state, he becomes the symbol of the state’s and society’s fecklessness as the “Lotto Lout,” a tabloid celebrity whose violent and anti-social ways remain unchanged by his £140 million lottery windfall.

|

Yet for some reason Martin Amis feels the need to give his loutish Lionel a sort of doppelgänger in the form of his nephew, Desmond Pepperdine, who survives his uncle’s tutelage in evil by aspiring — can you credit it? — to the bourgeois contentments of marriage and family. It is almost as if Mr Amis felt there was something wrong with a work too artistic to be didactic and that he had to drag a little morality into the arena of pure art. It may be, as he claims, that readers today are “perfectly at peace with the unregenerate,” but I wonder if this is because they are grown-ups. I think it is the artists and other sophisticates who share Mr Amis’s love for the unregenerate who remain attached to what amounts to an infantile urge to repudiate the moral order by celebrating, albeit with insincere caveats, the crimes of such fabulous monsters as Alex or Lionel Asbo.

The relevance of the metaphor from human maturation to the author of Dead Babies lies, I take it, in the left-wing conceit that the moral order amounts to religion and religion amounts to fairy tales, only believed by children. Maturity and sophistication must therefore mean the same thing to them: an acquired sense, either jubilant or melancholy, that people are fools to expect others to observe any moral code whatever, even if they retain a sentimental and anachronistic attachment to one themselves. As that increasingly rare hybrid, a self-consciously “literary” novelist who tries to write for a general audience, Martin Amis must know that the general audience remains unsophisticated enough to demand a bit of morality, even though he mostly clings to the fashionable view that the conventional morality of everyday middle class life in Britain or America is nothing but a battered veneer ineffectually hiding the supposed reality — which, if it were real, would be more terrifying than comic — of mere savagery.

It would be easy to forget, given how amiable so many of our lefty-literary types are in person, how deeply invested they are in this model of the world if it weren’t for occasional reminders like the rebarbative Compliance by Craig Zobel. This is a movie “inspired by real events” which its admirers have taken to be a confirmation of the famous Milgram experiments at Yale in the 1960s purporting to demonstrate that there is a potential Adolf Eichmann in all of us, eager to ingratiate ourselves with authority by — if not positively relishing the thrill of — committing unspeakable acts against our fellow human beings. True, poor Becky (Dreama Walker), the teenage victim of Mr Zobel’s own fake experiment with a prank caller (Pat Healy) pretending to be a policeman, is subjected only to sexual assault rather than being herded along with the rest of her family, race and religion into a gas chamber, but the principle is presumably the same: authority speaks to an ordinarily decent lower-middle class American (Ann Dowd) and she’s on board for pretty much any amount of evil that that authority would care to name.

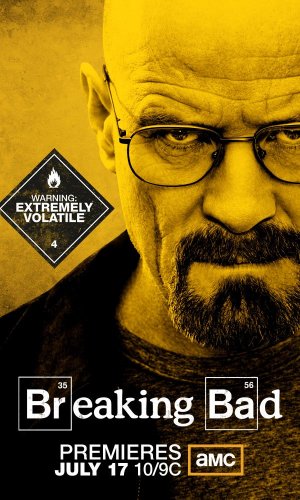

I think the idea is preposterous myself, though I recognize that I thus place myself in a tiny and shrinking minority, at least among movie-goers. Indeed, it would not be too much to say that, since David Lynch’s landmark Blue Velvet of 1986 if not before, evil barely hidden by conventional morality and respectability or evil made comic by its juxtaposition with the mundane — like Quentin Tarantino’s hit men discussing fast food — has been the norm among Hollywood’s artistic types, which is why Compliance has received the respectful if not ecstatic press it has. In more recent years, the work of both Mr Lynch and Mr Tarantino has grown ever more bizarre and remote from any recognizable reality, but their pessimistic or absurdist vision of the evil at the heart of everyday life has been adopted, so most people seem to think, by such marquee television series as The Sopranos, The Wire and Breaking Bad, all of them the inspiration for endless analysis and philosophizing among intellectuals and critics who come out of the same stable as Martin Amis.

|

Let me propose that they are all missing something. It is this. Anthony Burgess had to stick Alex and his droogs in a “dystopian” future and give them their own hipster argot to make their evil even somewhat believable. Martin Amis in Lionel Asbo feels confident enough of his shared vision of the world to dispense with believability altogether. He never pretends that Lionel is anything but a caricature of a tabloid bogeyman (itself, of course, a caricature) — which I guess makes Britain’s tabloid newspapers the real if overfamiliar evil he has chosen to satirize. But whenever we see evil placed in a believably familiar context in a hit television series like Breaking Bad, we notice it is not the simple, unadulterated evil of the Burgess-Amis fictional genre but something subtly different, not the horror of a barely imagined future without any moral standard but the nostalgia of a half-remembered past with an outmoded one. Breaking Bad’s Walt White (Bryan Cranston), like Omar Little (of The Wire) and Tony Soprano, fascinate not because they are evil but because they live in a world, as once we all did, in which, as Omar puts it “a man’s gotta have a code.”

And not only a code but the code — the same code of honor, in most respects, that Hollywood celebrated in the Westerns which were once its mainstay and which Tony Soprano makes a point of contrasting to the contemporary world. The equivalent moment of moral placement in Vince Gilligan’s Breaking Bad comes in the first season as Walt is, absurdly, making a list of pros and cons for the proposal he has put to himself to “Let him live” — him being the drug thug Krazy 8 (Maximino Arciniega) attached by the neck with a motorcycle D-lock to a pole in the basement. Under the pros Walt has six or eight variations on the theme that “Murder is wrong.” Under the cons there is only one entry: “He will kill me and all my family.” The comedy lies in Walt’s being so civilized as to believe there is still a balance between pro and con. As we get deeper into Breaking Bad, now paused half-way through a fifth and final season, Walt sheds this carapace of civilization and apparently sinks deeper and deeper into pure evil, yet he continues to hold our interest for the same reason his predecessors did, which is our deep suspicion that his world is the state of nature which both our conventional morality and its aesthetic repudiation have so long hidden from us — and that we may one day have to inhabit again ourselves.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.