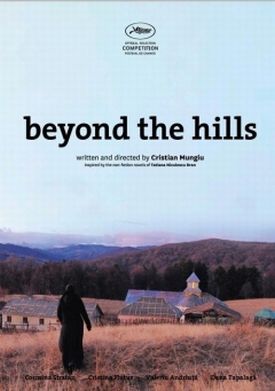

Beyond the Hills

One of the things I liked best among the many things I liked about Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2007, was that, while looking to liberals like the sort of liberal propaganda they have grown accustomed to from Hollywood, it was actually deeply subversive of the whole liberal project, at least so far as one of its central premisses, that of legalized abortion, is concerned. With his new film, Beyond the Hills (Dupa dealuri), he has repeated the trick, this time with religion. And not with just any old religion, or the kind of anodyne God-bothering that now passes for religion in most Western countries but that succeeds chiefly in bothering the romantic New Atheist crusaders of the media. No, this is a much more obvious target: a genuinely medieval form of Christianity that can survive in few places in the world, or even within the generally pretty backward Romanian Orthodox Church — the nominal authority under which a nameless priest/monk (Valeriu Andriuta) and “Papa” to a covey of nuns runs his unconsecrated monastery a long way from anywhere.

Both the monastery’s remoteness in the Romanian countryside and its failure to attract any higher ecclesiastical official to consecrate it — ostensibly because it remains unpainted, owing to lack of funds — are significant. One of the youngest sisters, the gentle, bovine novice Voichita (Cosmina Stratan), is visited by her best friend from the orphanage where they both grew up. Alina (Cristina Flutur) is a much more mercurial character who has emigrated to Germany to work as a waitress and now returned in the hope of persuading Voichita to join her in the West. There is a suggestion — which may only be sucker-bait for the liberals — that they have had a lesbian relationship in the past. Whether they have or not, however, Voichita is now firmly attached to the monastery and its ancient ways, and poor Alina like a moth to a lantern — the monastery has no electricity or running water — beats herself against the light into a state of moral and physical exhaustion in an attempt to break her friend’s new attachment.

Indeed, she even goes so far as to suggest that she is willing to become a nun herself if it means that the two can be together, and she gives all her meager savings to the monastery. But when Voichita urges her to allow the love of God into her soul, she replies: “I would rather just you love me.” There’s a hilarious scene in which one of the nuns reads out to Alina a list of 464 sins, asking her to write down the numbers of the ones she has committed as a preparation for her confession and absolution, and Alina patiently writes down every number, one after the other. But for the most part this is a story of nothing but grim desperation on all sides as Alina slips into and out of a state of violent hysteria which the religious imagine to be and treat as, according to their immemorial custom, a form of demonic possession. Obviously, a happy ending is hardly to be expected.

|

But the great thing about the movie is that the desperation is not confined to this remote and isolated community, which might otherwise appear to be a religious version of The Shining’s Overlook Hotel. Mr Mungiu offers us a vital context for the movie’s ever more harrowing scenes of attempted exorcism in the form of momentary but strategically-placed points of contact with the outside world, including the West which, as Papa says, “has lost the true faith. There nothing is sacred; everything is permitted.” Not that things are any better in secular Romania. Alina, we learn, came to the orphanage as a young child when her father hanged himself. A foster family with whom she lived and for whom she worked for a while has no further use for her and has robbed her of part of her savings. The state-run hospital is too overwhelmed to do anything but send her back to the monastery after sedating her in response to her first bout of hysteria. No one in the world wants her or is willing to help her save those in the monastery who, however benighted their methods, act out of manifest Christian charity.

The final point of contact with the wider world comes just as, it seems, the anachronistic little island of love and fear and superstition in the back of beyond is about to be swallowed up by the secular order — which adds to its indifference to pretty much everything and everybody else a particular contempt for the religious. Two policemen sit in their squad car unseen by us. We only see what they see through the windshield: a snowy cityscape with the noise of construction (or is it destruction?) in the background and workers visible on the road in front of them as the wipers intermittently clear away snow and slush. The prosecutor can’t see them yet, as he’s out on another case, one says to the other. An 11 year old boy stabbed his mother and put the photos up on the Internet. “What a world!”

“Will this winter ever end?” asks the other

“It will pass.”

The audience, or at least that part of it which has been paying attention, may be less certain.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.