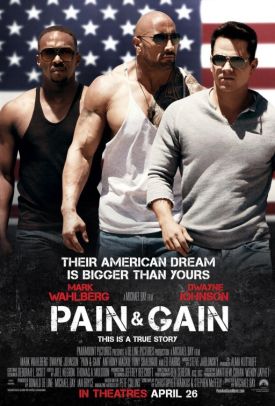

Pain & Gain

Michael Bay’s Pain & Gain, based very loosely on a true story as told in a series of article in Miami New Times by Pete Collins, comes to its too-long delayed ending as the closing credits are played out to the tune of Coolio’s “Gangster’s Paradise” of 1995 — the same year in which the events dramatized in the film took place. The lyrics, insofar as they can be understood, are rather introspective for a rap song:

Too much television watchin’ got me chasin’ dreams

I’m an educated fool with money on my mind. . .

Nothing unusual about that, of course, though the educated fool — an ironic designation? — is at least slightly unusual for saying such things (ostensibly) about himself. The characters in Pain & Gain are not blessed with even this degree of self-awareness. When the muscle-bound lame-brain Danny Lugo (Mark Wahlberg), the leader of the film’s ad hoc criminal gang, explains to Paul Doyle (Dwayne Johnson): “I’ve watched a lot of movies Paul; I know what I’m doing,” he doesn’t know that we’re laughing at him. Yet he and the other gang members — the third of the trio is Adrian Doorbal (Anthony Mackie) — are not incapable of learning either, and the movie, which shares some of its characters’ shallowness, is at least capable of laughing at itself.

But it doesn’t always succeed in walking the delicate line between a becoming self-irony and mere fakery. In fact, it almost never succeeds. Another bit of Coolio’s rap goes

Tell me why are we, so blind to see

That the ones we hurt, are you and me.

There’s a false note there, I think. In the context, at any rate, it doesn’t sound sincere. He must know very well why he is so blind to see. It’s because he has chosen and continues to choose this kind of blindness. Like the characters’ retrospective voiceovers in the movie which show a belated understanding of at least some of the evil they have done, this is confession for fun but apparently without what the Church calls a firm purpose of amendment — which is their counterpart of the movie’s own refusal to be ashamed of making light of their wickedness. When someone says that “Danny just wanted the American Dream,” it comes across as a feeble excuse in mitigation of his multiple offenses against law and morality rather than the absurdity it was presumably meant to be. The voiceovers hint of introspection and a moral dimension — even, perhaps, what they used to call the “moral” of the story — but this never really shows up.

Instead, the absurdities multiply to the point where everything is absurd, and the most horrific crimes become nothing more than laughing matters. The general lack of seriousness about the evil these men do is further reinforced by the fact that all three gang members are body-builders who meet in a seedy, down-at-heels gym in Miami and take a fancy to the more opulent life being lived by one of the gym’s clients, the profane and unattractive, half-Jewish, half-Colombian owner of a sandwich shop named Victor “Pepe” Kershaw (Tony Shalhoub). Likewise, Danny takes his inspiration from a motivational speaker named Johnny Wu — his mantra, “Don’t be a donter. Do be a doer,” is regarded with a quasi-religious awe by Danny — as inherently vacuous and ridiculous a figure as the steroid-injecting body-builders themselves.

Too stupid even to know what a notary is, Danny thinks he can torture Pepe into signing his wealth away to him and his fellow gang-members. The twist in the tale is that he actually succeeds, for a while, since the police are almost as stupid as he and his henchmen are. On the one hand, the addition of the forces of law and civilization to the ever-growing ranks of the hilariously dunderheaded is all just part of the comedy of the film’s portrayal of Miami in the 1990s; on the other hand, it takes us further away than ever from any possibility of moral seriousness — further away even than Ed Harris’s private detective Ed DuBois, the only character in the film who is both decent and intelligent, can single-handedly bring it back from.

It has long been apparent that the stupid are the last remaining class of people whom it is OK to ridicule, something which itself suggests the quasi-moral quality we now attribute to intelligence. In Pain & Gain, stupidity along with their sheer nastiness — both considerably exaggerated for the purpose out of the source material — also serves to rob the criminals’ victims of our sympathy. Most importantly the bad guys’ stupidity is what makes us feel, as perhaps the crime itself as presented here cannot quite manage, that the guilty deserve to be caught and punished. In a way, that is, we are encouraged to take of Danny Danny’s own view in one of his less-successful moments of self-examination: “The police figured out what we already knew, that Victor was a half-criminal p***k who deserved to have bad things happen to him.” There’s a lot to laugh at in this movie, but every now and then we may catch ourselves and find the laughter dying in our throats.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.