Why They Fight

From The American SpectatorFour years ago in this space (see “Rotten Apples” in The American Spectator of September, 2009), I wrote that movie violence, like movie sex, is inherently fantastical. This is because the context in which both sex and violence are normally experienced in real life is so radically different from that in which we experience it in the movies that the movie version necessarily and radically falsifies what the camera is ostensibly looking at. I quoted Quentin Tarantino’s dictum that “Violence is the funnest thing you can do at the movies; it’s the funnest thing to watch” — which is why it belongs, in his view, to “pure cinema.” By that he means cinema divorced from any lingering pretense to represent reality — in which violence isn’t fun at all unless you are psychotic — but existing in an abstract realm whose images, whether of violence or of anything else, can only be made sense of by comparing them to other movies.

All this was a propos of my third annual Summer Movie Series, which consisted of eight films under the common theme of “Crime and Punishment.” This year’s seventh annual offering consisted of six films with the joint sponsorship of the Ethics and Public Policy Center and the Hudson Institute, under the general rubric of “Why We Fight: War Movies and War, Then and Now.” By thus insisting on the comparison between movie images of war and the reality they purport to represent, I might be thought to have undermined my own principle, laid down four years earlier, but violence in war is a bit of a special case. This is not only because most people still think that war is the one circumstance in which violence is justified and even necessary, but also because that moral anomaly is itself so remarkable that the violence in war movies is nearly always incidental to their larger moral purposes — often contained within their answer to my title question of “Why We Fight.” Mr Tarantino’s Inglorious Bastards, in which the moral purposes are as caricatured as the violence is an obvious exception.

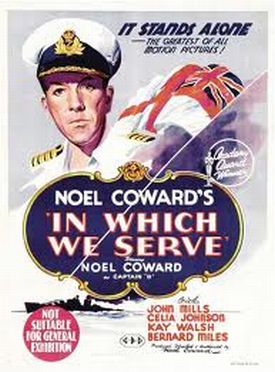

This summer’s series began with Noel Coward’s In Which We Serve, co-directed by David Lean, of 1942. Coward himself plays a fictional Royal Navy Captain, based on the real-life Lord Louis Mountbatten, in command of a fictionalized version of Mountbatten’s destroyer, H.M.S. Kelly, sunk off Crete in 1941. Most of the picture consists of flashbacks, meant to stand for the memories of the Captain and a small group of survivors who cling with him to a life-raft and are periodically strafed by German aircraft. Thus does the movie ingeniously make the connection between the men of the ship and between them and their families ashore, which shows us in practical, down-to-earth terms what both the country and fighting or dying for it mean.

|

In an even more understated form, the patriotic answer to the question of “Why We Fight” also lay behind the second movie in the series, John Ford’s They Were Expendable of 1945. Like In Which We Serve, this was based on real events and real characters who fought a valiant rearguard action in late 1941 and early 1942 to delay — prevention was never in question, given the massiveness of the forces arrayed against the small American garrison — the Japanese conquest of the Philippines. Also like In Which We Serve (and, I think, most of the best war movies), it was about a defeat. By its very historical nature, however, and the vast distances involved which prevented the reinforcement or resupply of American forces in the islands, the remoteness of the movie’s characters from those they left behind in the United States, rather than their closeness to them, is stressed here. That, in turn, means that Ford’s emphasis is more on duty than it is on patriotism. Patriotism is taken for granted, but almost every character — and especially John Wayne’s hot-headed Lt. “Rusty” Ryan — is confronted at some point with the necessity of suppressing his own feelings or wishes for the sake of the greater good. This happens most memorably near the end when Ryan and his commanding officer, played by Robert Montgomery, are both ordered to be evacuated, and the latter prevents the former from giving up his seat on the last plane for Australia by asking: “Who are you working for? Yourself?”

The poignancy of this moment, like much of the rest of the movie, depends on our knowledge of what happened to the characters’ historical equivalents, who had to be left behind to be captured by the advancing Japanese — namely death or appalling suffering on what came to be known as the Bataan Death March. But Ford leaves this, like the cause and country for which his heroes are fighting, off stage. Emotion in the audience is enhanced, rather than diminished, by its suppression on screen. And pushing it to the periphery is also a way of stressing at once the courage and the loneliness of the film’s heroes’ choice to do as duty requires. We are left with a sense of awe and mystery in the face of such bravery, rather than an easy confidence about our own understanding of any possible answer to the question of why they fight.

That’s also true of the third movie in the series, John Frankenheimer’s The Train of 1964, except that that movie goes out of its way to express skepticism about both patriotism and duty as even the background to the motivation behind its characters’ decision to risk their lives — and nearly all of them die — by fighting the Germans during the liberation of France in 1944. Burt Lancaster plays the French boss of a railway yard outside Paris when a German colonel, played by Paul Scofield, packs a train full of artistic masterpieces looted from the Jeu de Paume museum for shipment back to Germany ahead of the advancing allies. Although the paintings are referred to as “the glory of France,” and although the events of the movie are also but much more loosely based on real-life events, it is difficult for us to see the wish to stop this train from getting to Germany as reason enough for the main French characters to do as they do. It is difficult for Burt Lancaster’s character, who is also a leader of the Resistance, to see as well, and at every moment a decision is presented to him he rejects the idea of risking his men’s lives over a bunch of paintings whose fate, one way or the other, will do nothing to delay or hasten the now-inevitable liberation. Yet again and again he risks their lives and his own to stop it — at a terrible cost and in spite of his own best judgment.

|

Thus Frankenheimer makes the existentialists’ point that the decision to fight is its own justification, as also does Stanley Kubrick in Full Metal Jacket of 1987, the fourth film in the series — except that by echoing the anti-war movement’s portrayal of American troops in Vietnam as testosterone-crazed, kill-happy automatons, the movie is not just skeptical about duty and patriotism as reasons to fight but actively hostile to them, as it is towards any merely moral justification for war. To Kubrick, who himself takes up an amoral or even anti-moral approach to his material, all such justifications are mere pretexts for the real psycho-sexual motivations of the warrior. That, without the over-layer of anti-Americanism, is also the thinking behind Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker of 2009, except that her hero, a bomb-disposal expert in Iraq, played by Jeremy Renner, is hopped up on adrenalin rather than testosterone. Like Kubrick, Miss Bigelow appears to have no time at all for moral explanations of why we fight, though she doesn’t imply (as he does) that no such explanations exist.

The one movie of the last half-century whose moral understanding of war would be recognizable, I think, to the original audiences of In Which We Serve or They Were Expendable, is Black Hawk Down (2001) by Ridley Scott, the fifth movie in the series. His answer to the question of Why We Fight is the very old-fashioned concept of honor — though, tellingly, he does not use the word. Good as it is, however, the movie cannot quite avoid the taint of Tarantino-like cartoonishness which has marred (when it has not ruined) almost everything to come out of Hollywood for the past 40 years. Unlike those wartime movies mentioned above it doesn’t leave us with very much of the sense of mystery and awe behind acts of great daring and sacrifice, but it still sees them as both mysterious and as belonging to the lives of ordinary human beings rather than the fantastical if entertaining creatures of Stanley Kubrick’s or Kathryn Bigelow’s imagination. More than almost any other movie to come out of Hollywood in the last 20 years, it gives me hope for a serious American movie industry after cartoon-fever, otherwise the sickness unto death, has passed — though, admittedly, it’s not much of a hope.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.