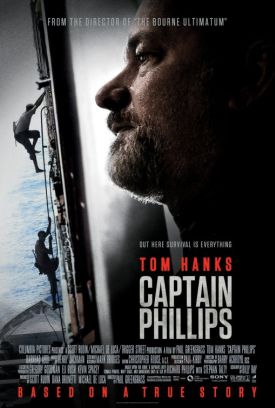

Captain Phillips

Somebody had to write it, of course. In the event it turned out to be Christopher Orr of the Atlantic, though any number of critics these days might have done the same. Here’s the lead of Mr Orr’s piece about Captain Phillips, Paul Greengrass’s true-life tale of piracy in the treacherous waters of the Arabian Sea off the coast of Somalia in 2009:

A tiny cohort of poorly organized insurgents, in a feat of terrible miscalculation, hijack an enterprise vastly larger than themselves, demanding a large and implausible ransom. Outnumbered and surrounded, they soon begin bickering with one another, their plans changing by the hour. Although repeatedly offered an out if they will simply release their hostage, they find themselves too deeply wedded to the self-destructive course they’ve charted. “I came too far,” their leader explains. “I can’t give up.” Is Paul Greengrass’s Captain Phillips the most inadvertently resonant movie of the year?

Oh, I get it. He means that those Wascally Wepublicans who are (or were when the piece appeared) brutalizing and holding hostage President Obama and his pathetic band of defenseless Democrats are just like the Somali pirates in Mr Greengrass’s film — except that the film feels a great deal more sympathy toward the gun-toting pirates than Mr Orr or his fellow partisans have shown any signs of toward the Republicans or tea-partiers. Here’s yet more redundant proof that movie criticism and left-wing idiocy go together like a horse and carriage. Or a vast container ship and piracy.

So what else is new? But another part of the problem with movie criticism these days is that it is not critical enough — not nearly critical enough — and it therefore tends to be a mere adjunct of the multi-billion dollar marketing effort of the movie business generally. In fact, movie critics are for the most part as much hand-in-glove with those they report and comment on as the rest of the media is with the Obama administration and the Democrats in Congress — not to mention being equally dominated by unthinking leftism. Leftist assumptions are also the reason for the very odd perspective of Captain Phillips, or at least one that would have seemed odd a generation or two ago, and why it is a much less good movie than it otherwise might have been. Not that you will hear that from your average movie critic.

The problem is at bottom the same as it was with Mr Greengrass’s earlier movie, United 93 of 2006 — namely, that the only sort of hero who interests him is the victim hero, just as the only emotion on his cinematic palette is pathos. It’s probably that and not anything more overtly political which makes him focus on the relationship between the eponymous captain of the Maersk Alabama, played by Tom Hanks, and his captor, the leader of the pirates. This is an engaging character called Muse (Barkhad Abdi), and he is meant to be seen as mirroring his victim. “I’m the captain now,” he announces on bursting onto the bridge aboard the Alabama, having scaled its massive steel hull by flinging a grappling ladder from his ramshackle pirate skiff. And he speaks truer than he knows, for he, too, has bosses that think nothing of sending him into harm’s way; he, too, has a recalcitrant and complaining crew who think they’re being treated unfairly. Soon the Somali ragamuffin and his well-turned-out American opposite number are practically odd-couple buddies, as Muse takes to calling Phillips “Irish” — a joking reference to his saying he is Yankee Irish.

Muse is really just a wayward boy caught up in a bad situation over which he has no control, just like the responsible American husband and father of a son lacking (so he tells his wife, played by Catherine Keener in a big-hair wig and an opening scene) in gumption and ambition. Muse, by contrast, dares to dream big dreams. One of them, so he tells his new friend, is of going to America — New York! — and buying a car. He insists that he and his men have only been driven to piracy because Somalian waters have been overfished by industrial trawlers from China and the West. The central moment of the film, apart from the emotional climax of the ending (about which more in a moment) comes as Captain Phillips says in fatherly fashion to Muse that “There’s got to be something other than being a fisherman or kidnaping people.”

“Maybe in America, Irish. Maybe in America,” says Muse, musingly.

|

Meanwhile, those who would once have been taken for granted by everybody as the real heroes of the story, namely the Navy Seals who (spoiler alert!) shoot the pirates by firing three kill shots simultaneously from the deck of a bobbing ship though the windows of the cramped cockpit of the lifeboat where Captain Phillips is being held hostage and might easily have been killed himself by the slightest mistake on their part — meanwhile, I say, these paragons of the military arts remain not only anonymous and all but wordless but positively drone-like in their lethal, inhuman efficiency. Any residual humanity they may possess is of no interest to Mr Greengrass or is meant to be to us. Maybe drones and other machines, or machine-like men, are now supposed to be our new heroes, as they are in Act of Valor, but they can’t really be said to make for very interesting cinema.

And who, indeed, can summon up much enthusiasm for such push- button warriors when Mr Greengrass’s camera, as mobile as Tom Hanks’s face, is alert for every ripple of emotion that crosses that face? Mr Hanks is there, we realize, not only as a personification of American decency but as a champion emoter, especially when it comes to the pathos that is as much the theme here as it was in United 93. But the audience interest which he thus gratifies is essentially a voyeuristic one. After his rescue there is a scene bordering on the obscene in its intrusiveness into what ought to have been the most privately emotional moment of this man’s life and his feelings of shock, horror, fear and relief on being rescued in the way that he is. Of course no one anymore, least of all a film-maker, can be expected to consider it a point of honor for a man to remain in control of his emotions, like the tight-lipped heroes of old. As a character in Act of Valor says, you need to “put your pain in a box and lock it down” for “no one is stronger than a man who can harness his emotions.”

Nowadays, alas, it’s also true that no one is more boring, at least on the silver screen — as that movie itself amply demonstrated. I don’t wish to be too critical of Captain Phillips, which is a better one and never less than exciting, even though everybody already knows how it comes out. There is also a thrilling moment, maybe even one that is meant to be thrilling, when the pirates look with awe and horror at the approach of a sleek U.S Navy warship and cry in dismay: “It’s the Americans!” Not many movies these days would dare to produce such a retro feeling of pride and triumph amongst all the pathos. The movie culture he is caught up in is no more Mr Greengrass’s fault than the critics who are disposed to find in his movie a critique of “global capitalism” — or Republican budget hawks; no more, either, than his pirates are to blame for the pirate culture which he naturally assumes has produced them. But we need more Captain Phillipses in the critical community to point out the corruption of public taste which is ultimately what is responsible for the less than honorable interests and emphases of an otherwise gripping movie like Captain Phillips.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.